Angelina Hang – Life Science, Year 2

Abstract

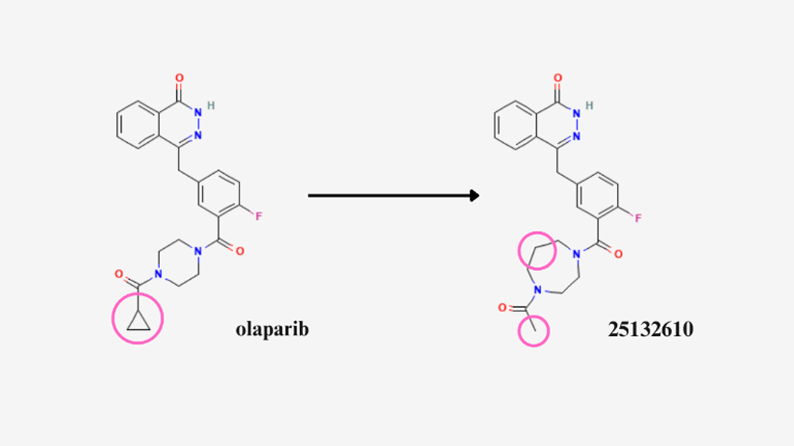

Breast cancer remains a very important issue in today’s world, killing 15 Canadian women every day. To treat breast cancer, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have shown promise in preventing the growth and development of cancer cells in the body. In particular, olaparib, an FDA-approved PARP1 inhibitor, is widely implemented in the medical field. This study attempts to enhance olaparib’s ability to bind to the PARP1 protein, through using computational biology software to dock conformers and compounds that have structural similarities to olaparib. Once docked, the kcal/mol values of each molecule are analyzed to determine what changes should be made to olaparib to increase its effectiveness as an inhibitor. It is found that 4-[[3-(4-acetyl-1,4-diazepane-1-carbonyl)-4-fluorophenyl]methyl]-2H-phthalazin-1-one (PubChem ID: 25132610) is the molecule with the most favourable kcal/mol values. Therefore, olaparib could be adjusted to create molecule 25132610 by replacing its cyclopropyl group with a methyl group, and adding an extra carbon. Using olaparib’s chemical structure as a foundation, the proposed modifications aim to develop a more effective alternative to current drugs used in breast cancer therapy.

Introduction

According to the Canadian Cancer society, 15 Canadian women die from breast cancer every day (Canadian Cancer Society, 2020). Therefore, breast cancer is still a very relevant problem in today’s world. Several studies have analyzed the causes of breast cancer, as well as which treatment methods are most beneficial (Łukasiewicz et al., 2021, Kim and Nam, 2022). Specifically, scientists have narrowed down a gene that is commonly associated with breast cancer: BRCA1 (National Cancer Institute, 2024).

What is BRCA1?

BRCA1 is an abbreviation for Breast Cancer gene 1 (National Cancer Institute, 2024). A common misconception amongst the public is that BRCA1 causes breast cancer (Canadian Cancer Society, 2020). In reality, BRCA1 plays a vital role in the prevention of breast cancer (McCarthy et al., 2014). The function of the BRCA1 gene is to produce proteins that help repair damaged DNA. If there is a mutation in the BRCA1 gene that inhibits it from doing its role, it can lead to tumors growing uncontrollably. Therefore, it’s more accurate to frame BRCA1 genes as tumor suppressor genes than cancer causing agents. According to John Hopkins Medicine (n.d.), only a small percentage of people carry mutated BRCA1 genes (approximately 0.25% of the population).

PARP1 Inhibitors: A Targeted Treatment for BRCA-Mutated Cancers

There are several methods used to target BRCA-mutated cancers, namely chemotherapy and radiation therapy (Łukasiewicz et al., 2021). In particular, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have shown promise as a maintenance treatment for breast cancer patients (Kim et al., 2022). PARP is a protein that assists cells with repairing themselves after damage. However, when a patient has cancer, PARP proteins can cause cancer cells to divide and multiply. Therefore, drugs that inhibit the PARP protein prevent cancer cells from repairing and growing, resulting in cell death, as shown in Figure 1 (Cancer Research UK, 2021). A medication called olaparib, also known as Lynparza, is an example of an FDA-approved PARP1 inhibitor, and will be the main molecule studied in this research (Cortesi et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Process highlighting the function of PARP inhibitors. (Dilmac et. al., 2023)

Modelling procedure: making changes to olaparib to improve binding affinity

The purpose of this study is to determine whether it is possible to make changes to olaparib, in order to create an inhibitor that might have a better binding affinity to PARP1, providing improved breast cancer treatment. However, in chemistry adding different elements to a compound changes the compound completely, meaning that by making adjustments to olaparib the new molecule will no longer be called olaparib. Therefore, this research uses olaparib as a basis or foundation for drug development, as it is simpler to modify an existing PARP1-inhibitor than to try to create an entirely new compound for this purpose.

In order to have a more controlled experiment, instead of arbitrarily adding different elements and functional groups to olaparib to make these changes, a similarity search in PubChem is utilized (Section 2.3). PubChem will scan and search for different molecules that are similar in structure to olaparib, for instance differing by an extra carbon or an addition of a methyl group. This allows the study to be based on molecules that adhere to realistic chemical rules and conditions, and also simplifies the docking and analysis process. It is important to consider the difference between similar compounds and conformers, where compounds refer to 2D structural similarities and the latter refers to 3D. Both variables are tested in this study in order to control for and examine whether 2D vs. 3D structural changes to olaparib play a role in binding affinity. Lastly, each molecule that is used in this study will be referred to by its PubChem CID number, which is unique to every compound and acts as an identifier.

Binding affinity will be measured using kcal/mol as the units. The lower or more negative the kcal/mol is, the better the affinity. This means that the act of the molecule binding to the PARP1 is more spontaneous and requires less energy input to occur. Through making changes to olaparib to increase its binding affinity to PARP1, a more enhanced and effective breast-cancer treatment drug can be developed.

Methods and Materials

Before experimenting with different adjustments to olaparib, a preliminary test was conducted through docking olaparib to PARP1, without making any changes.

Preparing for docking

The four-letter Protein Data Bank (PDB) code for the PARP1 protein bound to olaparib was retrieved from NCBI, which was under the label 7KK4. The structure was downloaded in a PDB format. The olaparib molecule was downloaded in a format suitable for ligand docking (sdf format) from PubChem (Dallakyan et. al., 2015).

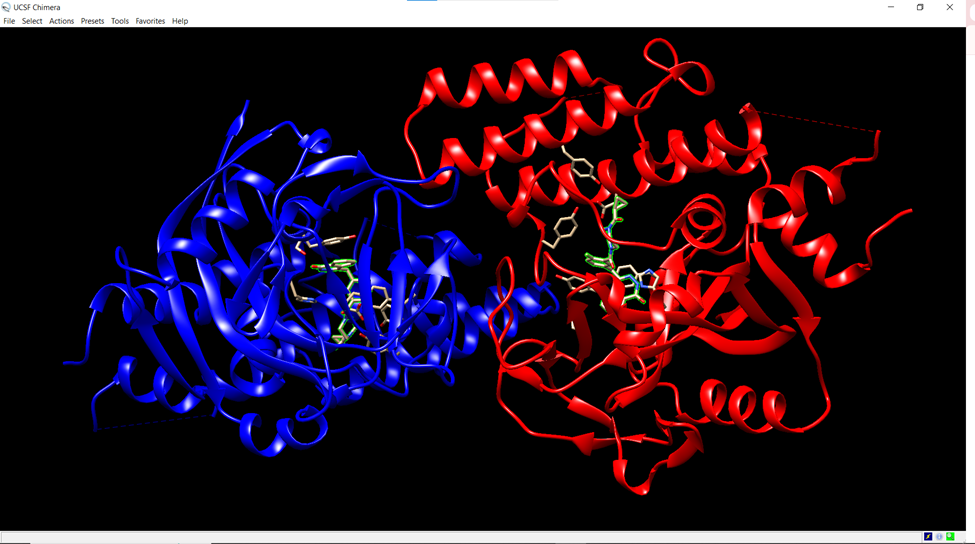

As mentioned, the PARP1 protein was bound to olaparib when retrieved from the NCBI protein database website. Therefore, in order to separate the ligand from the protein, UCSF Chimera software was downloaded (Pettersen, 2004). After opening the Chimera software, the PARP1 protein structure was uploaded by navigating to the “File” menu, selecting “Open,” and choosing the 7KK4 PDB file downloaded from before (Figure 2). The PARP1 protein was selected by clicking on the “Select” menu, then “Structure,” followed by “Protein.”

Figure 2. Screenshot from the Chimera platform. The PARP1 protein is highlighted in blue and red, while the olaparib molecule is beige.

The olaparib molecule was selected by navigating to the “Select” menu, choosing “Invert,” and selecting “Models,” which ensured the ligand (olaparib) nested within the protein structure was highlighted. The ligand was then removed from the structure by selecting “Actions,” then “Atoms/Bonds,” followed by “Delete.” The modified structure was saved by selecting “File,” then “Save PDB,” and the file was named “target.” The final step before docking was to download AutoDock 4.

Docking Process

To perform the docking, PyRx was used. PyRx comes with AutoDock Vina, which is a widely used computational biology software in academic research. The SDF file containing olaparib was added using the “Open Babel” tab of the PyRx interface. Once loaded, a right-click on the file allowed the conversion of the selected file to the AutoDock ligand format (PDBQT). Then, the “Vina Wizard” tab was opened and the “Start” button was clicked. After the conversion was finished, the molecule was added to docking through clicking its molecule name under the Ligand tab. To import the macromolecule (protein), the “Add Macromolecule” button was clicked. Then, the file named “target” was selected and added to the docking process.

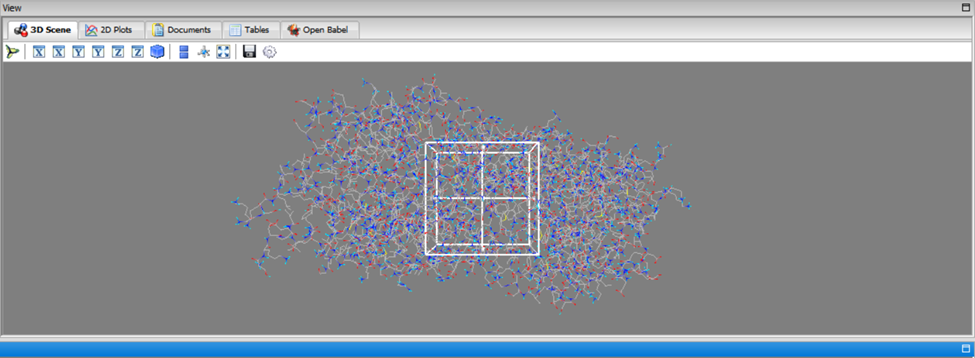

Once the Vina Wizard tab showed that one macromolecule and one ligand had been selected, the “forward” button was clicked. This led to the docking settings page. At the bottom left corner, there is a setting called “Exhaustiveness” with the value of 8. This setting controls the number of orientations the program will dock the molecule in. For this research, the default number of poses, 8, was kept the same. On the 3D scene display, there is a hollow cube that can be moved and adjusted based on the area of the macromolecule that the docking should be performed on (the active site). However, if the active site is unknown, under “Vina Search Space” a button called “Maximize” can be clicked. This will change the cube so that it encompasses the entire macromolecule, allowing the program to scan for the active site. To begin the docking process, the “forward” button was clicked once more.

For data analysis, once docking was completed the “binding affinity” column was used to retrieve numerical data. In PyRx, the units for binding affinity are kcal/mol, which serves as a basis for comparison between olaparib and similar structures. The binding affinity column has a kcal/mol value for each of the eight “modes”, or orientations in which the molecule was docked to PARP1. To calculate the average binding affinity of each molecule, the sum of all the kcal/mol values shown in the results was divided by the number of modes, which is 8 due to standard settings in PyRx.

Figure 3. Grid setting difference shown in PyRx

Modelling making changes to olaparib using PubChem Search feature

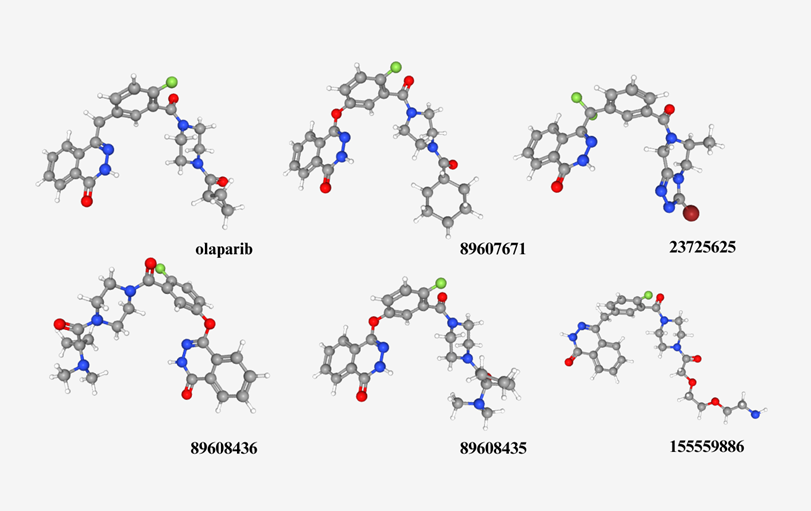

In order to mimic making changes to olaparib while still considering proper organic chemistry mechanisms, the PubChem Search feature was utilized. Upon searching “olaparib” in Pubchem’s database, a section can be accessed by scrolling down to 4.2. Related Compounds. There, two categories are shown: similar compounds (2D) and similar conformers (3D). Each category leads to a separate link, where molecules can be downloaded in a format suitable for the docking process shown in 2.2. In this study, the “relevance” filter was used to sort the molecules, and the top five results for the 2D and 3D categories respectively were downloaded and docked (Figure 4 & 5). The binding affinities for each molecule was also recorded, and based on analysis the molecule with the most favourable kcal/mol values (see Results section) was used to model potential changes that can be made to the olaparib molecule.

Figure 4. First five relevant molecules that have 2D similar structural properties compared to olaparib, using PubChem’s similarity search feature.

Figure 5. First five relevant molecules that have 3D similar structural properties compared to olaparib, using PubChem’s similarity search feature.

Results

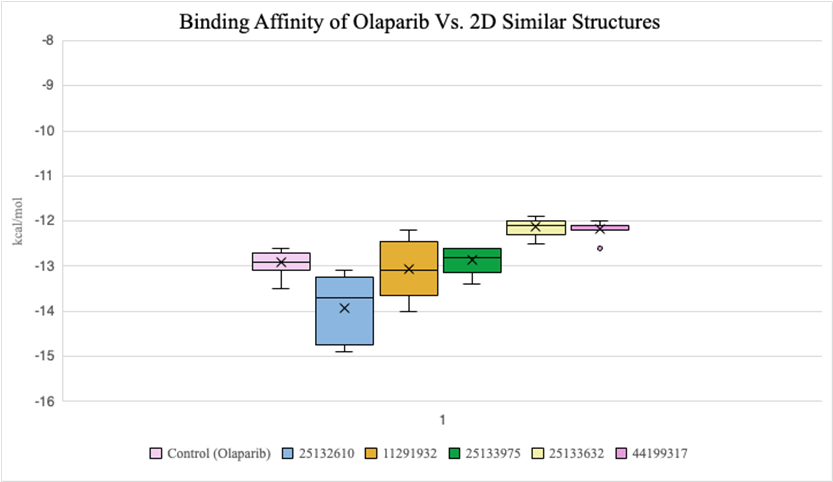

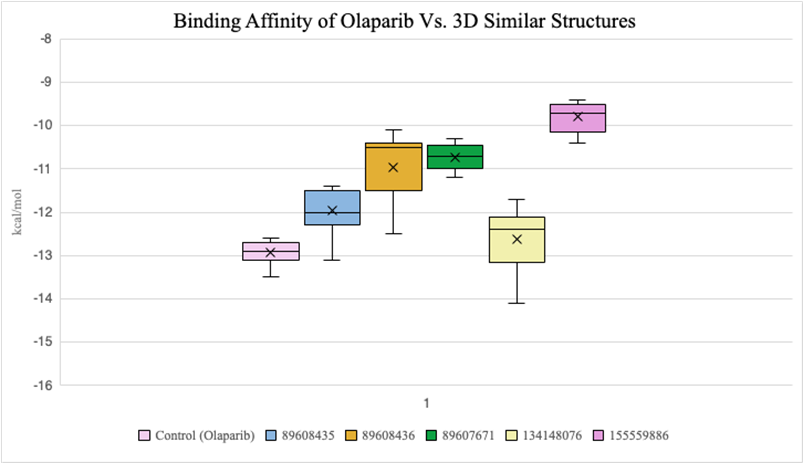

2D compounds that were docked (Figure 6) had lower average binding affinities, measured in kcal/mol, compared to 3D conformers (Figure 7). Both molecules 25132610 and 11291932 have smaller average kcal/mol values compared to olaparib. However, molecule 11291932 exhibited a larger range of binding affinity values than olaparib and molecule 25132610, with its highest value being around -12.2 kcal/mol.

Figure 6. Binding affinity comparison between olaparib and similar compounds (2D)

Figure 7. Binding affinity comparison between olaparib and similar compounds (3D)

Discussion

Analysis of Results

2D similar compounds had lower binding affinities compared to 3D conformers. This suggests that similarities to olaparib’s elemental composition had a bigger impact on binding ability than similarities to olaparib’s 3D orientation. In particular, molecule 25132610 showed the most promise in terms of favourable binding due to its low kcal/mol value, and olaparib can be adjusted based on the differences it has to molecule 25132610. This is significant as an inhibitor that takes less energy to bind to PARP1 means that it will act as a more efficient breast cancer treatment drug, disabling PARP1 from healing cancer cells that are meant to be removed from the body.

A hypothetical reason as to why similar compounds have a better binding affinity compared to conformers can be narrowed down to its elemental components. As shown in Figure 5, despite the molecules having a similar curve in its 3D orientation, its constituents are made up of fairly different elements, as shown by the different coloured balls and sticks. Whereas in Figure 4, the 2D compounds share a noticeably greater amount of similarities to olaparib, with a closer number of elements and more homogenous arrangements.

Conclusions

Molecule 25132610 binding affinity to PARP1 is the most favorable compared to the olaparib control and all molecules tested in this study, as its highest binding affinity value is still lower than olaparib’s average binding affinity value, and its smallest value reaching -14.9 kcal/mol, as shown in Figure 8. Therefore, in terms of changes to the olaparib, it is hypothesized that the binding affinity of olaparib can be improved by replacing olaparib’s cyclopropyl group with a methyl group, as well as adding an extra carbon (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Raw kcal/mol values after docking molecule 25132610 to PARP1.

Figure 9. Circled differences between olaparib and molecule 25132610

Lipinski’s rule of five

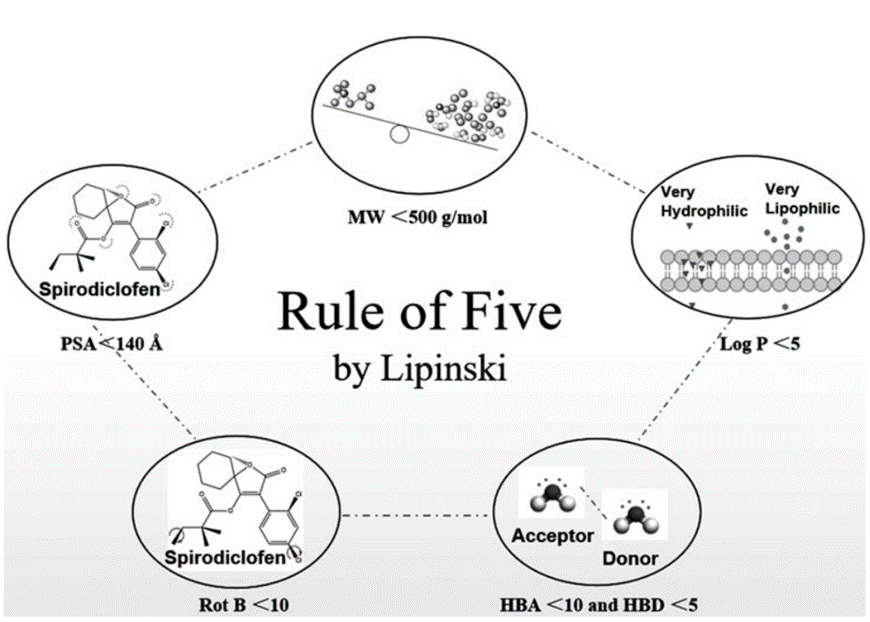

In drug discovery, Lipinski’s rule of five (Figure 10) serves as a guideline and a general predictor of whether a drug candidate can be orally bioavailable or safely ingested (Roskoski, 2019). In order to analyze whether molecule 25132610 met this set of rules, its chemical and physical properties were accessed through section 3.1 of its PubChem database (Figure 11).

Based on its properties, it is hypothesized that the molecule 25132610 is indeed an orally bioavailable drug. Its molecular weight, 422.5 g/mol, meets the Lipinski requirement of being less than 500 g/mol. Its hydrogen donor count of 1 is under the maximum which is 10, and the hydrogen acceptor count does not go over the maximum value of 5. Molecule 25132610 also has a very favourable LogP value of 1.8, and its rotational bond count and polar surface area all fulfill Lipinski’s rule of five.

Figure 10. Diagram explaining Lipinski’s rule of five (Chen et al., 2020)

Figure 11. Computed properties of molecule 25132610 according to section 3.1 of its PubChem database.

Limitations

Although PyRx is a computational biology software used in several professional research settings, in silico methods can only serve as predictions since they are simply mathematical values of how much energy it is supposed to take for the molecule to bind (Zoete et al., 2009). Wet lab techniques should be applied, for instance finding the 25132610 molecule and attempting to dock it to a PARP1 protein will be able to confirm the results.

It is also important to address potential flaws in PubChem’s search database feature. Relevance might not be a search variable for the most accurately sorted compounds from most to least similar. Since a small sample size was taken for compounds (5 out of 834), this can introduce potential underrepresentation of results. However, for conformers there were only 7 matching results on PubChem for structural similarity, so a sample of 5 can accurately represent the population of similar conformers to olaparib.

Future Research

Further studies with a larger library of compounds similar to olaparib could help identify molecules with stronger binding affinity to PARP1 than molecule 25132610. In addition, the safety and bioavailability of molecule 25132610 should be evaluated through in vivo trials. Given that it meets all criteria of Lipinski’s Rule of Five, its oral viability appears promising.

The present study has identified molecule 25132610 as a promising alternative to current drugs used for breast-cancer treatment, due to it using up less kcal/mol to bind to PARP1. These findings demonstrate the potential of computational biology to accelerate drug development, ultimately improving the effectiveness and efficiency of treatments for life-threatening diseases such as breast cancer.

References

Canadian Cancer Society. (2020) Breast Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Society, cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/breast/statistics.

Cancer Research UK. (2021) PARP Inhibitors | Targeted Cancer Drugs | Cancer Research UK. Www.cancerresearchuk.org, www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/targeted-cancer-drugs/types/PARP-inhibitors.

Chen, X., Li, H., Tian, L., Li, Q., Luo, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Analysis of the Physicochemical Properties of Acaricides Based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five. Journal of Computational Biology. https://doi.org/10.1089/cmb.2019.0323

Cortesi, L., Rugo, H. S., & Jackisch, C. (2021). An Overview of PARP Inhibitors for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Targeted Oncology, 16(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-021-00796-4

Dallakyan, Sargis & Olson, Arthur. (2015). Small-Molecule Library Screening by Docking with PyRx. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 1263. 243-250. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19.

Dilmac, S., & Ozpolat, B. (2023). Mechanisms of PARP-Inhibitor-Resistance in BRCA-Mutated Breast Cancer and New Therapeutic Approaches. Cancers, 15(14), 3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15143642

Gajiwala, K.S., Ryan, K. (2020). Structure of the catalytic domain of PARP1 in complex with olaparib. https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7kk4/pdb

Kim, D., and Nam, H.J. (2022) PARP Inhibitors: Clinical Limitations and Recent Attempts to Overcome Them. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(15), 8412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158412.

Łukasiewicz, S., Czeczelewski, M., , Forma, A., Baj, J., Sitarz, R., Stanisławek. A. (2021) Breast Cancer—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies—an Updated Review. Cancers, 13(17), 4287. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13174287.

McCarthy, A.M., Armstrong, K. (2014). The Role of Testing For BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Cancer Prevention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(7), 1023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1322.

Medline Plus. (2020) BRCA1 Gene: MedlinePlus Genetics. Medlineplus.gov. medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/brca1/.

National Cancer Institute. (2024) BRCA Mutations: Cancer Risk & Genetic Testing. National Cancer Institute. www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet.

NCBI. (2020) BRCA1 DNA Repair Associated [Homo Sapiens (Human)] – Gene – NCBI. Nih.gov. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/672.

Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem, 25(13): 1605-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20084.

Roskoski, R. (2019). Properties of FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors. Pharmacological Research, 144, 19–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2019.03.006

Ryan, K., Bolaňos, B., Smith, M., Palde, P. B., Cuenca, P. D., VanArsdale, T. L., Niessen, S., Zhang, L., Behenna, D., Ornelas, M. A., Tran, K. T., Kaiser, S., Lum, L., Stewart, A., & Gajiwala, K. S. (2021). Dissecting the molecular determinants of clinical PARP1 inhibitor selectivity for tankyrase1. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 296, 100251. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.ra120.016573

Zoete, V., Grosdidier, A., & Michielin, O. (2009). Docking, virtual high throughput screening and in silico fragment-based drug design. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 13(2), 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00665.x