Sana Seraj – Life Science, Year 2

Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem that can impact everyday life. As a result, scientists worldwide are trying to find alternatives and there is an emerging interest in using natural antibiotics, such as spices and herbs. Two well-documented examples of these include garlic and oregano. The purpose of this experiment was to test garlic oil and oregano oil against Escherichia coli (E. coli) K-12and to see whether their combination would enhance antibacterial activity. A disk diffusion method was used to determine the inhibition zones and thus antibacterial activity of each group. The results suggest that combining them would not create synergy, as oregano alone had the highest average inhibition zones. The study also noted that garlic oil yielded no antibacterial activity, despite past research proving it to be effective against E. coli. Therefore, further research is needed to determine the cause of this discrepancy.

Introduction

According to Maharjan et al. (2011), since antibiotics have been introduced to our world, they have become increasingly ineffective as time has passed. This has happened because bacteria have evolved to counteract the effects of certain antibiotics. Bacteria have two primary ways in which they can resist antibiotics. The first way is called intrinsic resistance, whereby bacteria inherit resistance through their genetic makeup, enabling them to be antibiotic-resistant naturally (Gehad & Springle, 2020). The other way is for them to develop resistance over time in their lifespan from methods such as horizontal gene transfer and spontaneous mutations (Gehad & Springle, 2020). There is one theory that the origin of intrinsic resistance was bacteria producing antibiotics to compete with each other (Gehad & Springle, 2020). In order to not kill themselves in the process of this, the species gains resistance to the antibiotic compound. The genes could then have been passed to pathogenic bacteria through methods like horizontal transfer. Currently however, the widespread excessive use of antibiotics has caused growing resistance, motivated by random DNA mutation (Gehad & Springle, 2020).

Because of the rise in antibiotic resistance, there is growing interest in viewing spices and herbs as alternatives to counter this. A cross-sectional survey of around 700 individuals in the United States found that a significant number of people (51%) were inclined to use spices as a complementary and alternative medicinal therapy (Jiang, 2019). Natural products within herbs and spices have been found to be antibacterial due to the different bioactive compounds like “alkaloids, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, tannins, cumarins, glycosides, terpenes and phenolic compounds” within them (Maharjan et al., 2011). A study by Gehad and Springle (2020) noted that metabolites exhibit antimicrobial qualities by lowering the bacteria’s pH or binding themselves to bacterial proteins, hence why they can kill them. In addition, metabolites can harm microbial membranes, disrupt cellular metabolism, and decrease microbial toxin production as well, explaining why they are antibacterial agents.

Certain spices have been observed to have more success in inhibiting bacteria, in particular garlic (Allium sativum), oregano (Origanum vulgare), onion (Allium cepa), and clove (S. aromaticum). In a study by Billing and Sherman (1998), these spices were seen to have inhibited bacteria by around 100%, with the exception of clove being able to inhibit around 85%. These spices and herbs have high antibacterial qualities for many reasons. Research by Bongiorno et al. (2008) found that one of the most effective antibacterial spices was garlic. This is because they found that garlic’s antibacterial agents are active against many strains of bacteria (such as “Shigella dysenteriae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp, Salmonella spp, and Proteus mirabilis”), and even more strains that are very resistant to current antibiotics. Another article concludes that this is because of the presence of allicin (the strongest antibacterial agent within crushed garlic), which is created thanks to the enzymatic transformation of allinase on alliin (Singh & Singh, 2018). It’s been revealed that a whole grass of oregano can create oregano essential oil, which has the ability to inhibit meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by affecting its cell permeability, metabolites, key enzymes, and reducing its ability to produce its toxin (Cui & Zhang, 2019). This is because of the presence of phenolic compounds like carvacrol and thymol, which give it antimicrobial properties (Pezzani et al., 2017). Research by Kabrah et al. (2016) found that onions contain a compound called flavonoids, which are very effective antimicrobial compounds. Cloves were found to have high antibacterial performance because they have a component called eugenol, an important compound that is known to be essential in its inhibitory abilities (Souza et al., 2005). It is noted in literature that essential oils’ antimicrobial properties (thymol, carvacrol, and eugenol) could be associated with many things, including their hydrophobic nature and their ability to partition the microbial plasmatic membrane. This disruption within the bacterial membrane allows them to have strong antimicrobial effects (Souza et al., 2005).

The methods used to evaluate the antibacterial properties of spices and herbs influence the results of the experiments. The type of extraction method, whether aqueous, ethanolic, or any other type of solvent, will influence how much of the bioactive compounds are extracted. A study by Bar et al. (2022) revealed that aqueous extracts of garlic yielded greater extraction of allicin than ethanolic ones, with a 10-fold difference. This is possibly due to water being a higher polarity solvent, therefore having a greater capacity to stabilize compounds with polar characteristics such as allicin. Thus for garlic, the solvent type determined the concentration of allicin, which was correlated with the compound’s antibacterial abilities. Other testing conditions such as pH can also affect the inhibition zones. An article by Ahmed et al. (2015) showed that the antibacterial effect of garlic decreased as the pH level increased. However, at higher pH and temperature, although reduced, garlic still retained some of its antibacterial effects, marking it as an effective antibacterial agent under different conditions. However, Arora and Kaur (1999) reported a different relationship between temperature and antibacterial ability, observing that when certain spices (garlic and clove) were prepared in hot water, there was no difference in their antibacterial abilities. However, for garlic extract specifically, upon being refrigerated for 6 days or filtered through filter paper, the antibacterial activity decreased by 15-29%, and it lost its antibacterial abilities entirely upon autoclaving. Raw garlic however was reported to show increased antibacterial activity under different incubation temperatures, potentially due to the formation of a new antimicrobial agent. This discrepancy was interesting, and further investigation could shed more light on this issue.

Other studies have considered whether combining herbs increases or decreases their antibacterial activity, such as Gutierrez et al. (2008), who yielded positive results when combining essential oils of multiple herbs. When oregano and basil were combined in this study, it was seen that there was a large increase in lag phases compared to oregano alone, which showed that the combination had enhanced antibacterial abilities. Another study investigated spices and herbs being combined, but only combinations of extracts from galangal (Alpinia galanga), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and lemon iron bark (Eucalyptus staigerana), and not the spices and herbs known to be highly antibacterial (Weerakkody et al. 2010). One problem yet to be looked into in all of these experiments to the author’s knowledge is if combining spices and herbs with high antibacterial qualities will increase or diminish their inhibition zones.

For that reason, the following experiment aims to determine the effects of this. The objective is to see whether combining garlic and oregano (a spice and herb known to be capable of high antibacterial activity) will produce synergistic effects. Escherichia coli. (E. coli) K12 will be used, which has been commonly utilizied in past experiments for evaluating the antibacterial abilities of spices and herbs. If effective, this research could be very important in the search for natural antimicrobials, by offering a different approach in tackling antibacterial resistance.

Materials and Methods

Ten LB agar plates were poured into Petri dishes, and after cooling into a gel, the plates were labelled. After this, a saline solution was prepared for the E. coli suspension. 0.9 g of table salt was added to ~99 ml of distilled water and mixed with a glass stirring rod for 30 seconds. Using a pipette, 1.5 ml of saline solution was transferred to a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube. To prepare the bacterial suspension, a stock plate of E. coli K-12 was obtained, and 3 colonies were put into the 1.5 ml saline solution with an inoculation loop. The suspension was gently mixed for five seconds, and then 160 µl was added to each plate. The suspension was spread equally across the plate using an L- spreader.

Then, disk diffusion commenced. For the garlic and oregano groups, 20 µl of pure garlic essential oil (Deve Herbes) or organic oregano oil (Herba) was added to each of the disks (Biogram) respectively. For the garlic and oregano mix plates, 10 µl of garlic and 10 µl of oregano oil were added to each disk. For each test group, three treated disks were added to three Petri dishes respectively. One additional plate was used as a negative control with just agar to ensure no contamination. The plates were incubated for 7 days. After one week had elapsed, the diameter of each inhibition zone was measured using a ruler and recorded.

Results

A total of three trials were completed for each of the garlic (Figure 1a), oregano (Figure 1b) and mix (Figure 1c) groups.

Figure 1: Zones of inhibition for a)garlic, b) oregano, and c)garlic and oregano mix plates after 7 days of incubation

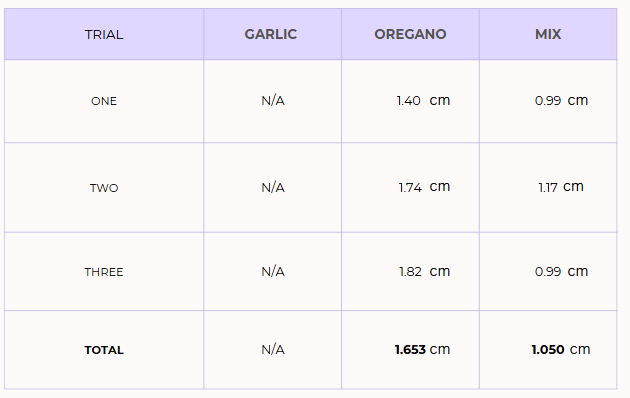

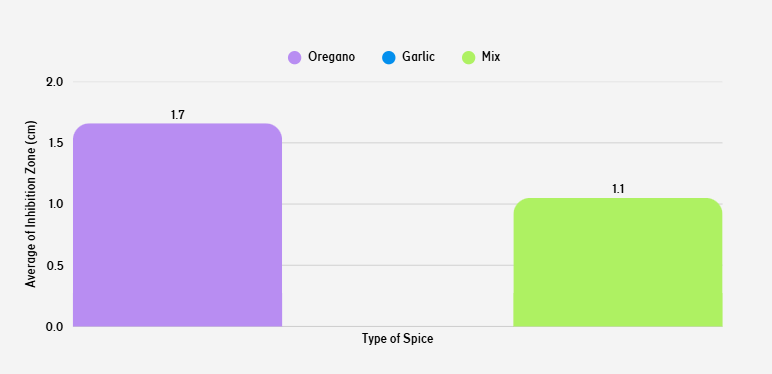

A total of 27 disks were tested across three trials and categories. The mean diameter of the observed zones of inhibition are reported in Table 1. The results suggest that oregano alone yielded the biggest inhibition zones, with a mean zone of inhibition of 1.653 cm across three trials (Figure 2). After oregano was the mix of oregano and garlic, with a mean inhibition zone of 1.050 cm, and finally was garlic, which had no inhibition zones.

Table 1: Mean Inhibition Zone for Each Spice In Each Trial

Figure 2: Measurements of the mean inhibition zones of each spice in centimeters

While the garlic group in trial three plate one did not display clear zones of inhibition, it did have clearer areas surrounding it compared to all other plates, suggesting some antibacterial activity (Figure 3). Similarly, there was also an unusual effect that certain disks had a curvature or circular shape around them, which was observed in all the test groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Garlic disks having clearer surroundings (not inhibition zones however)

Figure 4: Atypical circles/curvatures around the inhibition zones found in certain plates in all test groups.

Discussion

Results and Interpretation

The data from this experiment revealed that combining garlic and oregano oil did not increase the inhibition zones, but rather decreased it compared to oregano alone. Contrary to the original hypothesis, on average, oregano oil produced the largest inhibition zones (1.653 cm), followed by the mix of oregano oil and garlic (1.050 cm), and finally garlic oil alone. It was surprising that garlic oil alone often showed no inhibition at all, as this did not line up with earlier research papers. There was one plate, trial three plate one, where the garlic did not have a zone of inhibition per se, but the area around the disk was clearer than the rest of the plate (Figure 3). One possible reason for this however could be that garlic oil leaked out of the disk and caused that reaction. The results of garlic contradict many research articles, such as Billing and Sherman (1998) and Bongiorno et al. (2008), who claimed that garlic was very effective in inhibiting bacteria. One factor contributing to its lack of efficacy in inhibition zones could be due to the garlic oil not having any allicin, as explained in a study by Amagase et al. (2001). Since allicin is an unstable water-soluble and oil-soluble compound, and the garlic oil used was extracted through steam distillation, which eliminates water-soluble compounds completely, allicin would have been removed completely by the end of the process. Because of that, pure garlic oil does not have allicin, but rather contains compounds such as oil-soluble sulphur compounds like diallyl trisulfide (Amagase et al., 2001). Consequently, because of the method of extraction, there is a decreased amount of allicin within the final oil, compared to freshly crushed garlic extract. That being said, in a paper by Yasin et al. (2022), garlic oil was used against E. coli and yielded results. Interestingly, out of all the bacterium tested, E. coli had some of the smallest and largest inhibition zones on average compared to the other bacterium, yet was also one of the most resistant strains of bacteria. This could also account for the limited effect of the garlic oil on the growth of the bacteria. The oregano oil data aligns with past research on its antibacterial properties.

A study by Gutierrez et al. (2008) could explain why the mix of garlic and oregano did not produce larger inhibition zones than garlic or oregano alone. The authors tested the efficacy of plant essential oils in combination with each other against E. coli and other bacterial strains. Against E. coli specifically, oregano combined with rosemary had no result, while other combinations had moderate to great efficacy (however no combination showed “clear synergistic effect”) (Gutierrez et al., 2008). For example, oregano and thyme, both very strong antibacterial agents on their own, did not synergize, which could be what happened to garlic and oregano. It is possible that since garlic contains sulphur compounds, while oregano and thyme have phenolic compounds, this decreased the overall antibacterial properties rather than increasing them (Amagase et al., 2001)(Pezzani et al., 2017)(Gutierrez et al., 2008). The composition of each compound is also important. It is noted within the paper by Gutierrez et al. (2008) that when carvacrol and its precursor p-cymene, work together, the p-cymene is able to help carvacrol enter the bacterial cell membrane easier, thus improving the spice combination’s efficacy. Yet for garlic and oregano, while a major compound in oregano essential oil is p-cymene (8.90%), it’s not a major component in garlic essential oil (Sidiropoulou et al., 2020). However, despite the lack of p-cymene and having used 50% less oregano in the mix plate as compared to the oregano-only plate, the inhibition zones were not on average 50% smaller than the oregano alone. This could be possible due to garlic’s antibacterial agents working with oregano’s antibacterial properties and providing an increased antibacterial effect, despite the lack of p-cymene.

Around some of the plates, there was also an atypical circle/curvature a few millimetres away from the inhibition zone (Fig. 4). One reason for this could be that during the application of the E. coli suspension, the L-spreader was dragged into the agar because of the excessive pressure, creating divots which created this phenomenon.

Addressing Limitations/Challenges

Selecting an appropriate test method proved difficult and created many challenges for gathering quantitative data. The method initially chosen for this experiment involved adding powdered spices to melted LB agar before pouring the plates. This method however led to sparse quantitative data because the spices within the agar caused difficulty in seeing and counting the E. coli colonies correctly, requiring the experiment to be restarted. The issue of quantitative data was solved by switching to disk diffusion, yet another issue had to be dealt with. An infusion was made by combining garlic, oregano, and water, yet the first infusion created did not have enough powdered spice within it to provide measurable inhibition zones. In order to address this issue, the infusion’s spice content was adjusted and increased. However, the inhibition zones stayed cloudy. The extraction method was switched from infusions to pure garlic and oregano oil as a way to prevent contamination and also increase the concentration of the spice. This finally allowed for results.

The possibility of cross-contamination affecting the second trial is possible as the same pair of tweezers was used for all of the disks. While this limitation is not likely to have influenced the primary results of this study, it explains the contamination found on several plates. Also, on many of the plates there was condensation, which smeared colonies, and thus prevented data from being gathered from those inhibition zones. The plates that were distorted by condensation were excluded, while plates with condensation that was not touching the inhibition zone and was less than 2 mm, were included.

The data from this research project allowed for speculation regarding different aspects of combining spices and herbs and accentuated some factors that may inhibit the effectiveness of these combinations. While subject to sources of error, this experiment offers insight into this little-studied subject, aiding in the search for effective natural antibacterial agents. Future experiments could increase the amount of allicin by using various extraction techniques for the garlic variable to determine why this discrepancy has occurred. Subsequent trials afterwards could combine other spices and herbs that are known for their antibacterial properties such as clove and onion. The effect of temperature on inhibition zones could also be investigated. Gathering this information would be beneficial in the long-term research for substitute antibiotic options.

References

Ahmed, M. A., Ravi, S., & Ghogare, P. (2015). Studies on Antimicrobial Activity of Spices and Effect of Temperature and pH on Its Antimicrobial Properties. IOSR Journals. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Studies-on-Antimicrobial-Activity-of-Spices-and-of-AneesAhmed-Ravi/afa840806a36c100822938b91b2e7d4a1bb81921

Amagase, H., Petesch, B. L., Matsuura, H., Kasuga, S., Itakura, Y. (2001). Recent Advances on the Nutritional Effects Associated with the Use of Garlic as a Supplement. November 15-17, 1998. Newport Beach, California, USA. Proceedings. (2001). The Journal of nutrition, 131(3s), 951S–1123S.

Arora, D., S., & Kaur, J. (1999). Antimicrobial activity of spices. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00074-6

Bar, M., Binduga, U. E., & Szychowski, K. A. (2022). Methods of Isolation of Active Substances from Garlic (Allium sativum L.) and Its Impact on the Composition and Biological Properties of Garlic Extracts. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 11(7), 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11071345

Billing, J., & Sherman, P. W. (1998). Antimicrobial Functions of Spices: Why Some Like it Hot. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 73(1), 3–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3036683

Bongiorno, P. B., Fratellone, P. M., & LoGiudice, P. (2008). Potential health benefits of garlic (Allium sativum): A narrative review. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine. https://doi.org/10.2202/1553-3840.1084

Cui, H., Zhang, C., Li, C., & Lin, L. (2019). Antibacterial mechanism of oregano essential oil. Industrial Crops and Products, 139, 111498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111498

Gehad, Y., & Springel, M. (2020). Characterization of antibacterial properties of common spices: Journal of emerging investigators. Journal of Emerging Investigators. https://doi.org/10.59720/20-069

Gutierrez, J., Barry-Ryan, C., & Bourke, P. (2008). The antimicrobial efficacy of plant essential oil combinations and interactions with food ingredients. International journal of food microbiology, 124(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.02.028

Jiang, T. A. (2019). Health benefits of culinary herbs and spices. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL. https://doi.org/10.5740/jaoacint.18-0418

Kabrah, A. M., Ashshi, A. M., Faidah, H. S., & Turkistani, S. A. (2016). Antibacterial Effect of Onion. Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311535680_Antibacterial_Effect_of_Onion

Maharjan, D., Singh, A., Lekhak, B., Basnyat, S., & Gautam, L. S. (2012). Study on Antibacterial Activity of Common Spices. Nepal Journal of Science and Technology, 12, 312–317. https://doi.org/10.3126/njst.v12i0.6518

Pezzani, R., Vitalini, S. & Iriti, M. (2017). Bioactivities of Origanum vulgare L.: an update. Phytochem Rev, 16, 1253–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-017-9535-z

Sidiropoulou, E., Skoufos, I., Marugan-Hernandez, V., Giannenas, I., Bonos, E., Aguiar-Martins, K., Lazari, D., Blake, D. P., & Tzora, A. (2020). In vitro Anticoccidial Study of Oregano and Garlic Essential Oils and Effects on Growth Performance, Fecal Oocyst Output, and Intestinal Microbiota in vivo. Frontiers in veterinary science, 7, 420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00420

Singh, R., & Singh, K. (2019). Garlic: A spice with wide medicinal actions. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 8(1), 1349-1355. https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2019.v8.i1.6946/garlic-a-spice-with-wide-medicinal-actions

Souza, E. L. de, Stamford, T. L. M., Lima, E. de O., Trajano, V. N., & Barbosa-Filho, J. M. (2005). Antimicrobial effectiveness of spices: An approach for use in Food Conservation Systems. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 48(4), 549-558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-89132005000500007

Weerakkody, N. S., Caffin, N., Lambert, L. K., Turner, M. S., & Dykes, G. A. (2011). Synergistic antimicrobial activity of galangal (Alpinia galanga), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and lemon iron bark (Eucalyptus staigerana) extracts. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 91(3), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4206

Yasin G., Saade Abdalkareem, J., Mahmudiono, T., Al-shawi, S. G., Rustem Adamovich, S., Shehla, S., Abed Jawad, K., Acim Heri, I., Marwan Mahmood, S., Mohammed, F. (2022). Investigating the effect of garlic (Allium sativum) essential oil on foodborne pathogenic microorganisms. Food Science and Technology, 42. https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.03822