Gillian Mok – Applied Science, Year 2

Abstract

A person’s postural sway is an indicator of their overall balance. Currently, there are no general-use devices that can be used to measure a person’s postural sway. The lack of accessibility is concerning for seniors as they generally have higher risks of falling. To address the issue, a general-use postural sway detector making use of an accelerometer was created. An experiment was then run to verify the device’s results in four separate scenarios, each with different degrees of the subject’s instability. We found that the device is able to detect small variations in balance well, with approximately 5% error compared to industry devices. The accuracy of the device drops as the posural stability becomes more pronounced, measuring with up to 50% error between trials, however it is a reliable tool for measuring less severe balance instabilities. Overall, the device’s low manufacturing cost means that the device has potential to be used in community and non-clinical settings as a screening tool.

Introduction

Many people, especially seniors, have balance problems which can increase their risk of falling-induced injury. Balance problems are also a symptom of health issues, such as Parkinson’s disease, or a result of previous afflictions, such as a stroke (Park et al., 2015). A person’s postural sway, or the movements a person makes to remain in an upright position, can be a good indicator of a person’s balance overall. Postural sway movements may be broken down into sideways motion (X-direction) and forwards and backwards motion (Y-direction).

Balance is determined by multiple factors in the human body. The eyes, inner ear, nervous system, and muscles all contribute to a person’s balance. Vision improves stability as part of a sensory feedback system: vision impairment has been demonstrated to reduce postural stability (Collings et al., 2015). The inner ear is also an important factor in determining a person’s balance. It provides sensory feedback on orientation and motion.

In order to adjust to the sensory feedback provided by the inner ear and eyes, a person’s nervous system will control the muscles in their body to make minute ajustments. These motions are more pronounced in cases where a person has existing balance problems (Yiou et al., 2018).

Based on a clinical study done by Røgind et al. (2003), a baseline can be established for normal postural sway. This baseline was taken using a force plate. They found a person’s Center of Pressure (COP)–the point in which the total force acting on a person’s foot or feet is concentrated– from the force plate, and then recorded the changes in this value over time. They found that as age increases, postural sway will also increase. There was also a larger postural sway value in those who consumed more alcohol or smoked.

A previous study run by Lo et al. (2022) tested the effectiveness of a custom force plate to measure postural sway. The goal of their experiment was to test the viability of a custom low-cost force plate. In their experiment, they had 40 participants test out the custom force plate in two separate sessions (Table 1). The data in the first two columns for the first row give the average velocity of the COP of the individuals in the two study groups when their eyes are open. Overall, their results showed excellent readability for younger participants, and more variability with older participants, a trend that is accurate according to the results of Røgind et al. (2003).

Table 1. Within-day reliability for different COP variables in young participants. (Lo et al. 2022)

Another system that was developed to measure postural sway was one done by Grafton et al. (2019). The study involved the testing of a head-mounted wearable device. Using Inertial Measurement Unit-based sensors, they measured different types of sway power in individuals, including linear sway power. None of the observed changes due to external variables, such as session-to-session variability or changes due to routine physical activity, exceeded the 95% confidence intervals. The success of this experiment suggests that measurements of postural sway with methods other than force plates are achievable.

Despite these studies, there are limitations to the current technology. Currently, the only way to measure the amplitude of postural sway is by using a person’s COP with a force plate. However, force plates require complex computation and the creation of biophysical models in order for them to be effective. The complexity of these devices make them difficult to use outside of a laboratory.

There are also no methods that have been used to measure the amplitude of a person’s postural sway using a variable other than a person’s center of pressure. The experiment done by Grafton et al. (2019) only focused on power, which neglects the variability in a person’s overall sway.

Most of the devices in use are used in data collection or as diagnostic tools. The current complexity of force plates make them infeasible to use in more general settings. Therefore, a gap in current research is the lack of an accessible device that provides detailed data to the user. Such a device could be used in physiotherapy to determine whether a treatment method is sucessful or not. Such a device could measure the velocity and displacement of a person’s center of mass in order to determine their postural sway. If such a device were easily accessible, it would give patients more autonomy over their health and recovery.

Method

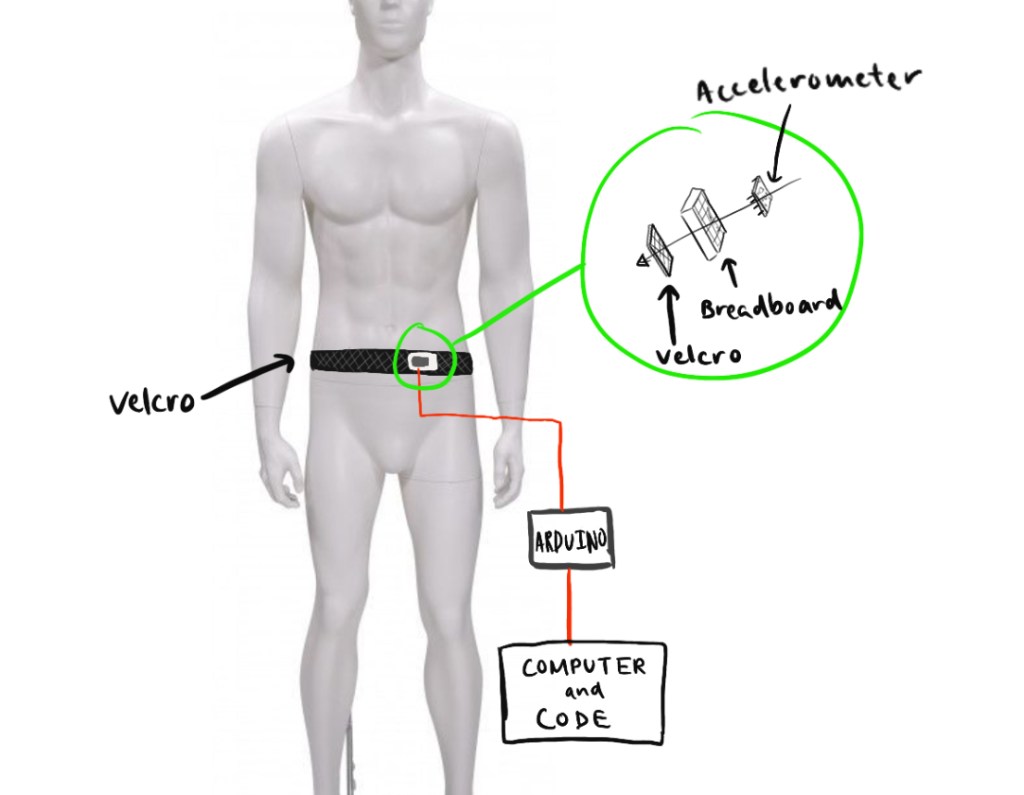

In order to adress the lack of an accessible balance monitoring tool, a device was created using an accelerometer (Adafruit BNO055 Absolute Orientation Sensor), a breadboard, an Arduino board (DFRobot Arduino Board and Shield), wires (DFRobot M/M Jumper Cables for Arduino), and Velcro (3/4 Inch Fastener Roll, SOURRI) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Components of the Device

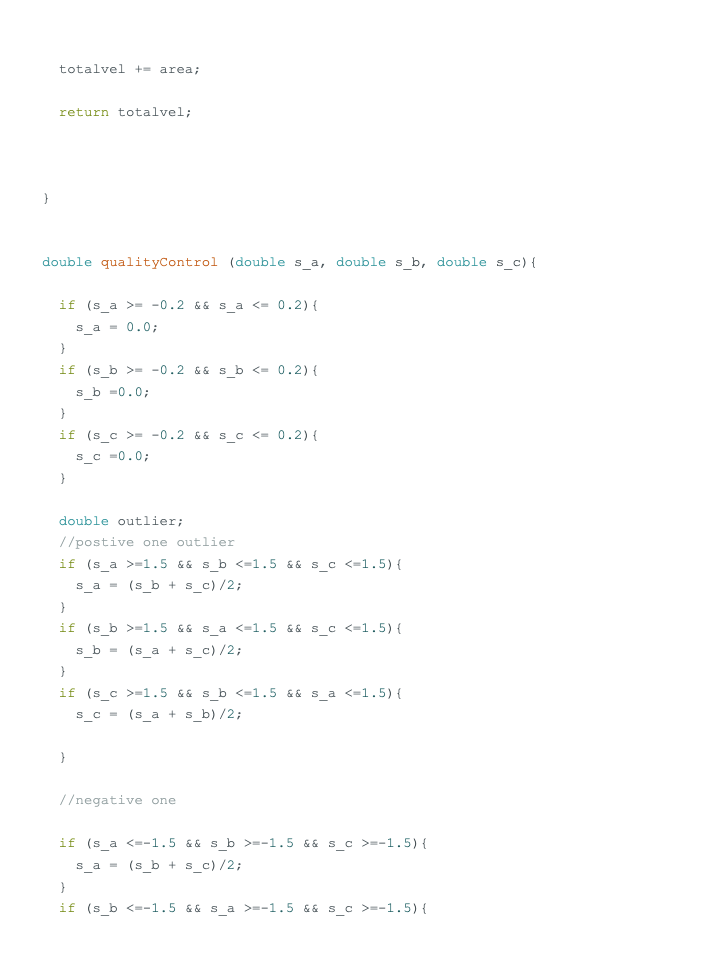

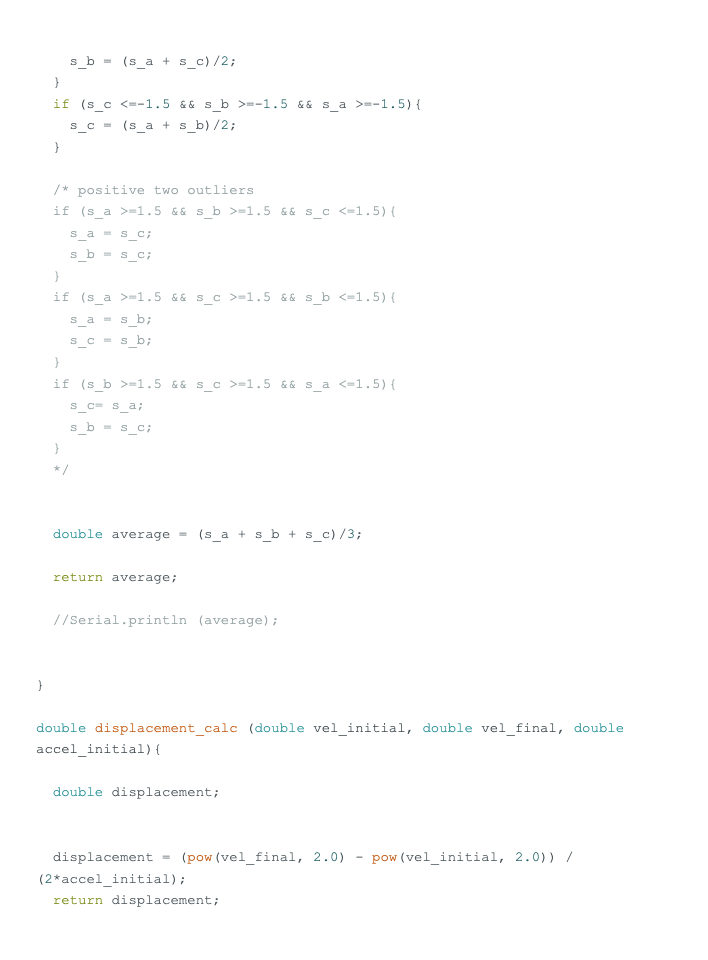

The accelerometer was soldered to copper pins and placed on a breadboard. The breadboard was then wired to an Arduino board. Using the Arduino IDE, code was written in order to calculate the change in x-direction velocity between two data sampling times. The velocity changes were averaged and noise-reduced to preserve accuracy and precision. The displacement of the accelerometer was then calculated using the acceleration and velocity values.

To mount the device, a velcro belt was used. The sensor module, consisting of the accelerometer, breadboard, and wires, was attached to the belt with a velcro patch stuck on the back of the breadboard. The wires extended to the Arduino board, which was connected to the computer (Figure 2).

The device’s code was written in C++, in the Arduino IDE. The base code for acceleration sampling was referenced from Townsend et al (2015). The accelerometer was coded to sample the acceleration every 25 milliseconds. From there, the code would integrate the acceleration-time graph in order to find the change in velocity. The velocity-time graph would then be integrated to find the displacement.

Figure 2. Diagram of Device Construction

Figure 3. Code Flowchart

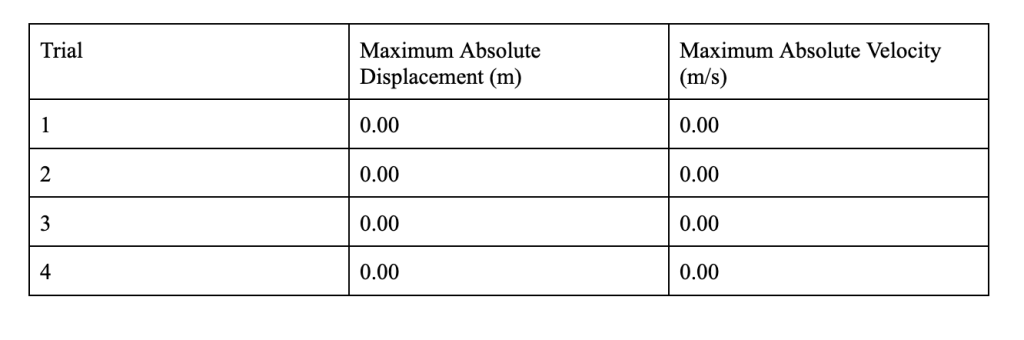

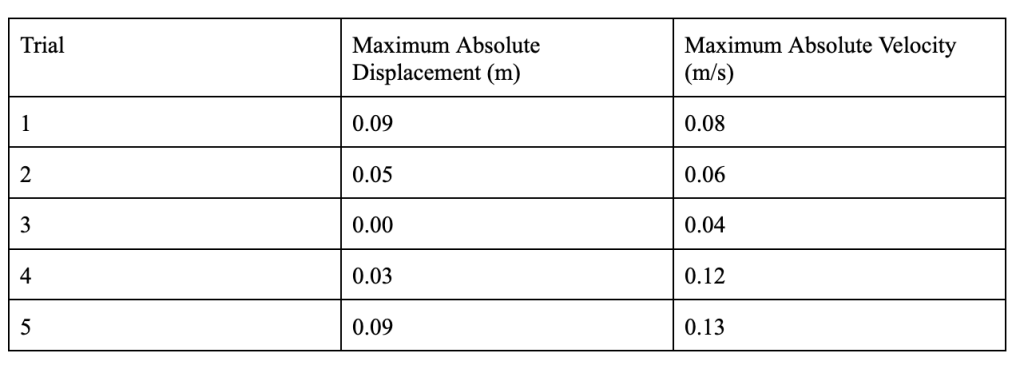

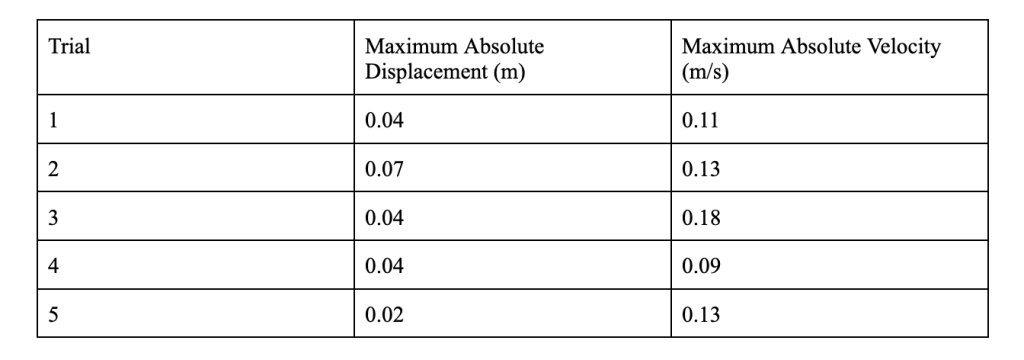

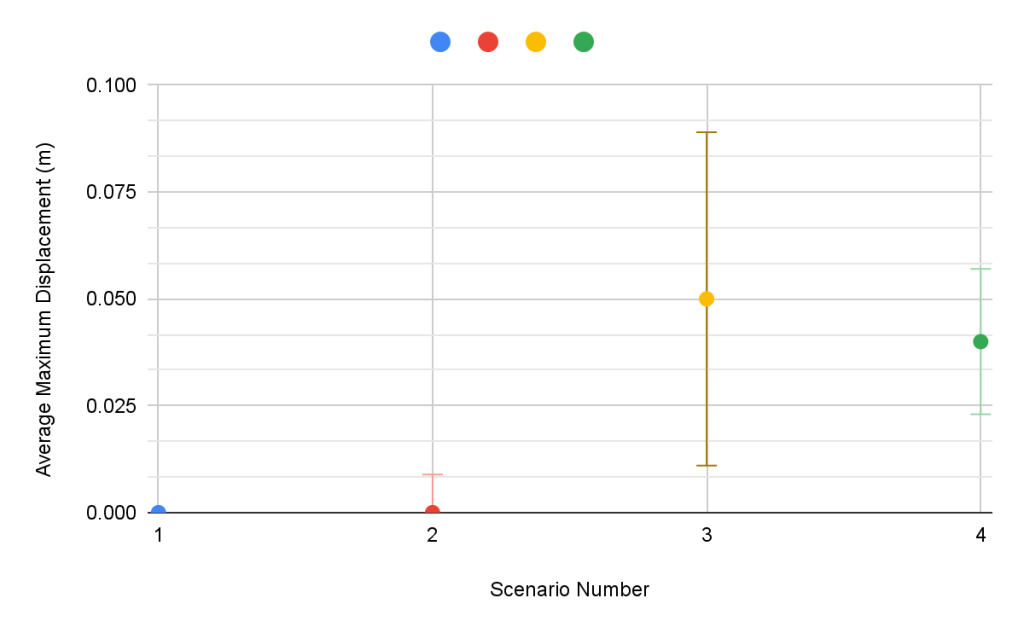

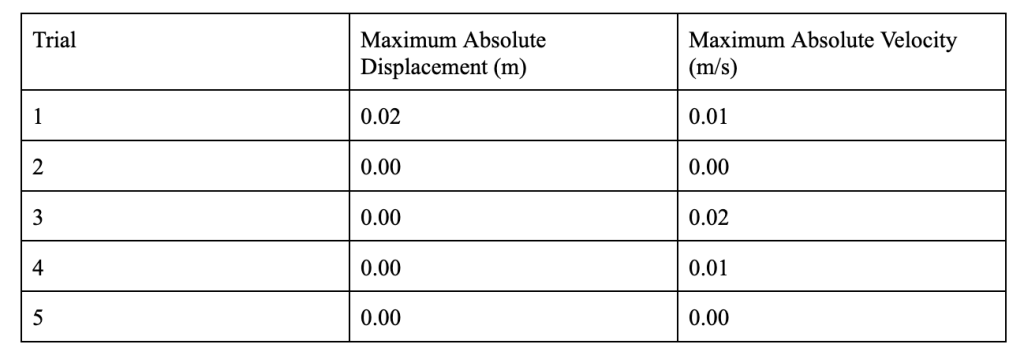

An experiment was performed in order to test the accuracy and feasibility of the device. A single healthy teenager was used as a test subject in the trials. The device was attached to the subject’s hips and data was recorded for different scenarios. In the first scenario, the subject was sitting down and stationary (Table 2). In the second scenario, the subject was standing upright (Table 3). In the third scenario, the subject was standing on one leg with both eyes open (Table 4). In the fourth scenario, the subject was standing on one leg with both eyes closed (Table 5). Each trial consisted of thirty seconds of data collection, except for Scenario 4, which had a data collection time of ten seconds. The maximum absolute velocity and maximum absolute displacement in the x-direction were then recorded (Table 6; Figure 4; Figure 5).

Table 2. Maximum velocity and displacement measured while the subject was sitting down (Scenario 1)

Table 3. Maximum velocity and displacement measured in while the subject was standing on both legs (Scenario 2)

Table 4. Maximum velocity and displacement measured while the subject was standing on one leg (Scenario 3)

Table 5. Maximum velocity and displacement measured while the subject was standing on one leg with closed eyes (Scenario 4)

Table 6. Average Maximum Velocity and Displacement for all Scenarios with Standard Deviation

Figure 4. Average maximum absolute displacement (m) for each scenario

Figure 5. Average maximum absolute velocity (m/s) for each scenario

Discussion

A higher scenario number corresponds with a higher degree of expected balance instability. As shown in Figure 4, the monitor is able to detect larger values of both displacement and velocity in cases where an individual’s balance is hindered by external factors. The device is able to detect small variations in balance well. When the subject was sitting down, the device detected an average maximum velocity of 0.00 meters per second (Table 6). When the subject was standing, the device was able to measure the subject’s small oscillations and the average maximum velocity was recorded as 0.01 meters per second. These values line up with the previous research done by Lo et al, whose measured average sway velocity while standing was 0.00996 meters per second (Table 1). The sensor is therefore able to detect small changes in postural sway with relative accuracy. For small variations, the sensor had less than 5% error rates.

Some limitations of the device are as follows: the accelerometer can only measure acceleration values with a precision of 0.01 meters per second squared, making the velocity and displacement calculations somewhat imprecise. As the sensor runs over a period of time, the rounding errors from a lack of precise data compound, making the sensor most useful when measuring data in short periods. To avoid compounding errors, a time period of 20 seconds or less should be used. Using imprecise data for the calculations, especially considering the loss of data that happens within the calculations, means that the value of the velocity and displacement results fall in a rather large range. For scenarios with pronounced instability, such as Scenario 4, the margin of error can be up to 50% of the original value, making the calculations inaccurate (Figure 5). The space between sampling times of the accelerometer means that the calculations have some degree of inaccuracy.

Preliminary results show that the sensor has potential in community, non-clinical settings as a screening tool. The device’s manufacturing cost was seventy dollars, making it much more affordable for individuals to use than professional testing. The device can be placed in health and community centers, family doctor’s offices, and senior homes in order to allow for easy access.

Future work on the device would benefit from using a more sensitive accelerometer. Additionally, future tests should use a large pool of test subjects in order to make the results more precise. Testing the device with a large population will allow the determination of the reliability of the results.

References

Collings, R., Paton, J., Glasser, S., & Marsden, J. (2015). The effect of vision impairment on dynamic balance. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research, 8(S1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1146-8-s1-a6

Grafton ST, Ralston AB, Ralston JD. Monitoring of postural sway with a head-mounted wearable device: effects of gender, participant state, and concussion. Med Devices (Auckl). 2019 May 1;12:151-164. https://doi.org/10.2147/MDER.S205357

Horak, F., King, L., & Mancini, M. (2014). Role of Body-Worn Movement Monitor Technology for Balance and Gait Rehabilitation. Physical Therapy, 95(3), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140253

Lo, P.-Y., Su, B.-L., You, Y.-L., Yen, C.-W., Wang, S.-T., & Guo, L.-Y. (2022). Measuring the Reliability of Postural Sway Measurements for a Static Standing Task: The Effect of Age. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.850707

Park, J. H., Kang, Y. J., & Horak, F. B. (2015). What Is Wrong with Balance in Parkinson’s Disease?. Journal of movement disorders, 8(3), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.15018

Røgind, H., Lykkegaard, J. J., Bliddal, H., & Danneskiold-Samsøe, B. (2003). Postural sway in normal subjects aged 20-70 years. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 23(3), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1475-097x.2003.00492.x

Townsend, K., Herrada, E. (2015). Adafruit BNO055 Absolute Orientation Sensor [Source Code]. Adafruit. https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-bno055-absolute-orientation-sensor/arduino-code

Yiou, E., Hamaoui, A., & Allali, G. (2018). Editorial: The Contribution of Postural Adjustments to Body Balance and Motor Performance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00487

Appendix

Appendix A:

Code