Dennis Shen – Applied Science, Year 2

Abstract

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is a process through which computers are trained to recognize characters appearing within an image. Recent advancements show promise for OCR to be applied to music. This study aims to create an open-source program that incorporates OCR to transpose alphabetical chords found in sheet music. The program was built with three main parts: image preprocessing, image OCR, and image postprocessing. Then, the program was tested against alphabetical chord sheets with lyrics found from the internet. The results shown by this method of transposing chords achieved an average accuracy of 78% across 66 tested images. These results indicate this program, with improvements to the accuracy, can enable alphabetical chord sheets to be more easily transposed. These possibilities may lead to a future of more accessible music and music education.

Introduction

Playing music requires a variety of skills – knowing how to play the notes on an instrument, knowing how to read sheet music, and having knowledge of music theory. One possible method of playing music is to read chords from a chord sheet. Tunyasanon et al. (2017) reported that these can often be found online in specific keys but take extra time to transpose into different keys for different instruments. While experienced musicians can use theory knowledge to transpose said keys, the difficulty and time cost is greater for amateur musicians. For students – often amateur musicians, a primary goal remains to learn to play the music.

Research has shown that discovery of the musical piece through playing it is crucial to the understanding of musical concepts (Fowler, 1970). From a broader education perspective, this principle still holds. Yannier et al., 2021 confirmed that students learned more through actively engaging in the learning process, where being physically active in their learning allowed them to improve pattern recognition, generalize their learning and improve their creativity. Additionally, 99% of students agreed that hands on building improved their technical skill development (Kline et al., 2021). These findings point to a benefit to be had from utilizing hands on tools in an educational setting. A field that has shown promise are digital tools. Research done by (Dancsa et al., (2023) concluded that digital tools can not only make the teaching-learning process successful but can also continuously improve the competence of learners. Furthermore, digital tools allow actively engaged students to improve their problem-solving, speaking and critical thinking abilities. Another study by Moreno et al. (2018) affirm this, stating that the use of mobile applications as an educational tool can support the construction of knowledge and improve the creativity of learners.

In music education, various digital tools and advancements bring hope to assist in musical learning. One advancement is with Optical Character Recognition (OCR), where computers are trained to recognize characters appearing on a page with various pattern recognition technologies (Mori et al., 1992). Stemming from this technology and advancements in OCR, various other tools such as Optical Music Recognition arose – where it attempts to allow computers to read musical notation. However, while Optical Music Recognition exists, the technology is often limited to a specific subset of musical inscriptions (Calvo-Zaragoza et al., 2021). Another advancement is using OCR to perform character recognition of various lyrics in musical composition. Notably, automatic lyric recognition is challenging – especially for older documents (Burgoyne et al., 2009). Tunyasanon et al. (2017) achieved a promising 80% accuracy for OCR followed by transposition of chord characters, such as A#. Their methodology consisted of reading the image, separating the chords from lyrics using a mathematical analysis, then applying musical transposition afterwards. However, the study conducted had a narrow testing dataset consisting of ten images, as well as no further implications on the accessibility of the resulting program.

While generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT allows for inputs of musical scores for OCR, there are limitations within educational settings regarding AI. A study done by Fullan et al. (2024) found that AI in educational environments may become a helpful educational tool, or a real danger to jobs and livelihoods. Additionally, they found that school leads are confronted by challenges posed by AI. These findings indicate that direct use of AI within educational environments may not be the most straightforward solution.

A facet to improve the efficiency and benefits of hands-on learning in a musical educational setting incorporates OCR technology. To reduce the time chord name transposition takes for both amateurs and professionals, a program of increased accuracy, broad distribution and testing rigor is proposed. The program will aim to combine an improvement in both OCR and transposition accuracy into a downloadable file, which can be utilized by various education institutions.

Materials and Methods

The Java programming language version 17.0.1 was used to create the application. There are four main steps in the process: Importing Libraries, Input and Preprocessing, OCR, and Post Processing. Testing was then done on 66 images with chords and lyrics.

Importing Libraries

The latest JavaCV and Tess4J libraries were imported into a Java project Maven file. In this case, the version for JavaCV was 1.5.11, while the Tess4J version was 5.13.0. The English training data was downloaded from the tesseract github. An English wordlist was downloaded as well from here. Words representing chords were removed from the wordlist. All single letters (A, B, C), flats (Ab, Bb, Cb) and also minors (Am, Bm, Cm) were removed.

Input and Preprocessing

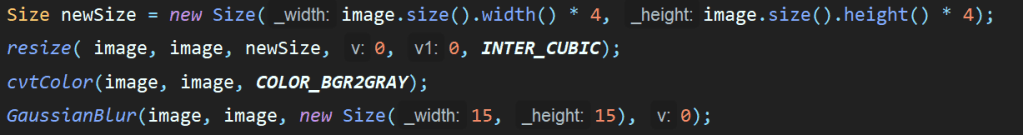

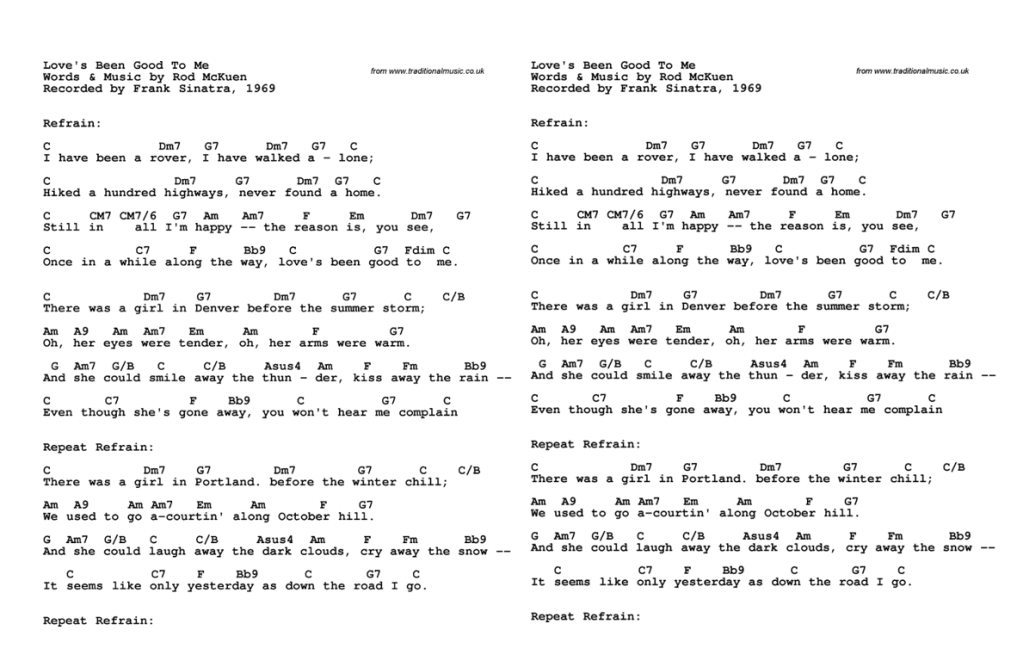

Input images were read through Java’s FileReader class and converted to Mat objects with the JavaCV library. These objects stored the image for processing. Then, three operations were performed with the JavaCV library (Figure 1). The image was resized to four times its original pixel scale (a 400×400 image becomes 1600×1600). Then, the image is converted to grayscale. Finally, the image had Gaussian blur applied with a kernel size of 15×15 pixels. This image was then saved (Figure 2).

Figure 1. The image resizing, grayscaling and the Gaussian blur functions

Figure 2. The input image prior to (left) and after (right) preprocessing

OCR

An instance of the Tess4J tesseract was created, which served as the sole model for OCR. A whitelist of alphanumeric characters, whitespace, forwards slash, periods was inputted into the Tess4J instance (Figure 3). The option to preserve spacing was kept to ensure output spacing matched with the original image. The image was then processed with this model to generate a string representing the image’s text (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The training data source, character whitelist and spacing preservation setting

Figure 4. The OCR text output (Shown on right)

Post Processing

A function was written to split the output into individual lines. Another function was written to split these lines into smaller strings according to spaces. These were then compared against the English word list. All lines not containing English words were classified as chords. Each line that was classified as a chord was transposed up a set number of half steps dictated by a pre-set variable. Further details about said function have been included in the appendix. Lastly, these lines were then put back into order and into a text file.

Figure 5. The text file after transposing up two half steps (shown on right)

Testing

Tests were performed on 66 Portable Network Graphic (PNG) images from the internet. The images contained only chords and lyrics. These images were resized to 1275 pixels wide, with their height scaled accordingly to mimic a sheet of letter paper at 150 dots per inch. Images were randomly ordered and split into 11 groups, corresponding to transposition up one to eleven half steps. The machine used in these tests ran using an Intel i7 1165G7 processor with 16gb of RAM.

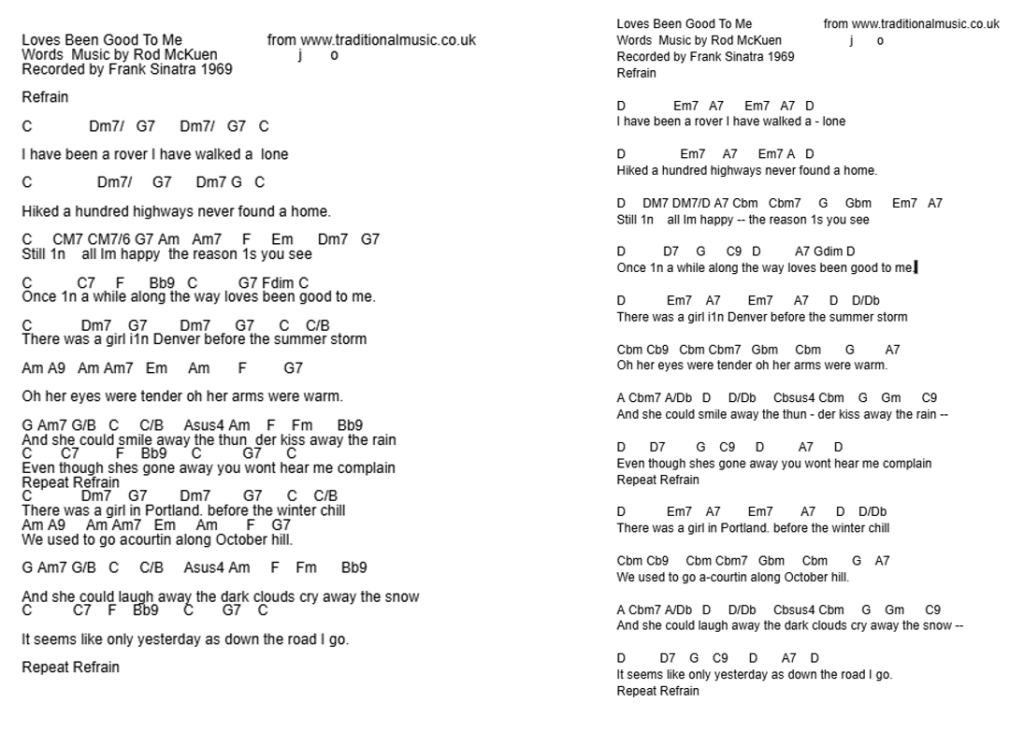

The images were inputted into the transposer and their output saved to an individual text file (Figure 6). The transposed text output was then checked manually for chord accuracy only. A chord was considered ‘correct’ if the root note after transposing, when played on the piano, would result in the correct pitch. A chord was considered ‘incorrect’ if it was missing, or if the root note was not ‘correct’. A chord was ‘hallucinated’ if there was no previous chord in the original image, yet the output file contained an extra chord.

Figure 6. Input image (Left) and output image (Right). Red are examples of ‘incorrect’ chords, blue are examples of ‘hallucinated’ chords

For each input and output, the number of ‘correct’, ‘incorrect’, and ‘hallucinated’ chords were counted. Results were tallied including and excluding the hallucinations. In results where hallucinations were counted, they contributed to both the total and the ‘incorrect’ count. In results where hallucinations were discounted, they contributed to neither the total nor the ‘incorrect’ count. The percentage accuracy for each type was calculated by dividing the number of ‘correct’ chords by the total number of chords.

The time to process each input function and output function was also measured in milliseconds by the Java system time as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Segment showing time calculation

An average time was calculated by taking the sum of all the times to process each of the images and dividing by the number of images. An average accuracy total for both including hallucinations and excluding hallucinations was taken by summing the percentage accuracies of each image, then dividing by the number of images.

Results

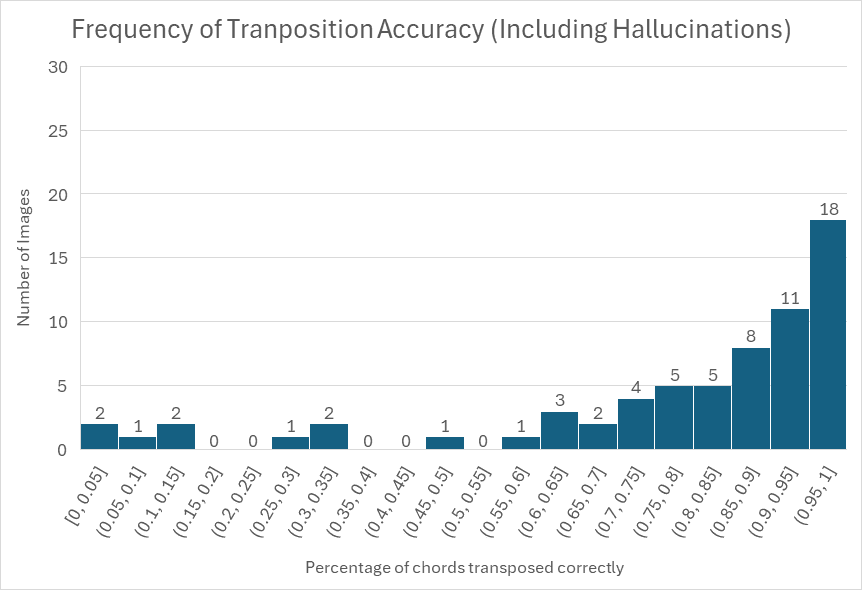

Figure 8 and 9 show the distribution of percentage accuracies of the transpositions.

Figure 8. A histogram showing the distribution of accuracy (excluding hallucinations)

Figure 9. A histogram showing the distribution of accuracy (including hallucinations)

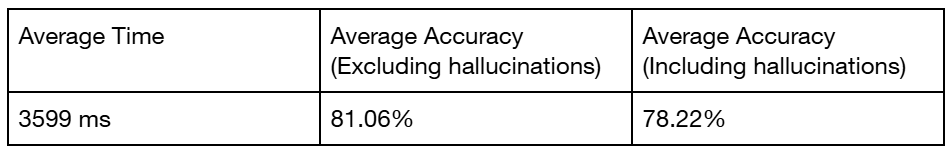

Table 1 showcases overall accuracy and time taken for all 66 images. Time is rounded to nearest millisecond, while accuracy is rounded to hundredth percent.

Table 1. Overall average time and average accuracy

Discussion

The results show promise towards developing a full-fledged application allowing transposition of chord sheets by taking a photo. The average accuracy with hallucinations was around 78%. This is roughly expected, as it was similar to the 80% of Tunyasanon et al. (2017). However, a greater number of tests performed (66 compared to ten) strengthen the claim.

Moreover, manual analysis found that the input image clarity likely impacted performance. While the images were all resized to an equal 1275 pixels wide, the true resolution of the image remained unchanged. For the input image shown in Figure 10, the output was largely incomprehensible.

Figure 10. A blurry image

However, if this program was made into a mobile application with images taken directly from a modern mobile phone, the clarity of the image should be consistent with the camera rather than online media

On this basis, some improvements to be made are with the OCR engine and preprocessing. A different modern OCR library such as Pytesseract or EasyOCR may allow for a greater ability to reduce hallucinations and inaccuracies in the OCR step. Adaptive preprocessing to each specific image may allow for superior input to the OCR engine, which can again improve accuracy.

Further improvements can also be made to the transposition function to allow for more musically accurate transpositions. Instead of merely being the same note on the piano (such as Cbb and Bb), have the function determine the key of the whole chord sheet and then transpose accordingly. This can allow for greater readability, as the chords now fit more clearly into a musical key but also may improve accuracy. Additionally, a graphical user interface can be added to make this program into a more user accessible application.

Conclusion

Overall, this program shows strong progress towards a greater accuracy when transposing chord sheets, achieving an average accuracy of just under 80%. Although there are future improvements to be made regarding the OCR component and musical accuracy, the open-source nature of this program also allows it to be a future step forward in improving accessibility to musical education and musical experiences for all.

Appendix

Code can be found at: Dennis-Shen/transposer

References

Burgoyne, J. A., Devaney, J., Pugin, L., Ouyang, Y., & Himmelman, T. (2009). Lyric extraction and recognition on digital images of early music sources. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277297348

Calvo-Zaragoza, J., Jr., J. H., & Pacha, A. (2021). Understanding Optical Music Recognition. ACM Computing Surveys, 53(4), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3397499

Dancsa, D., Štempeľová, I., Takáč, O., & Annuš, N. (2023). Digital tools in education. International Journal of Advanced Natural Sciences and Engineering Researches, 7(4), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.59287/ijanser.717

Fowler, C. B. (1970). Discovery: One of the Best Ways to Teach a Musical Concept. Music Educators Journal, 57(2), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/3392841

Fullan, M., Azorín, C., Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and school leadership: challenges, opportunities and implications. School Leadership & Management, 44(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2023.2246856

Kline, A., Kolegraff, S., & Cleary, J. (2021). Student Perspectives of Hands-on Experiential Learning’s Impact on Skill Development using Various Teaching Modalities . International Conference on Social and Education Sciences , 1–10. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED626321.pdf

Mori, S., Suen, C. Y., & Yamamoto, K. (1992). Historical review of OCR research and development. Proceedings of the IEEE, 80(7), 1029–1058. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.156468

Moreno, H. B. R., Ramírez, M. R., Rojas, E. M., & del consuelo Salgado Soto, M. (2018). Digital education using apps for today’s children. 2018 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2018.8399329

Tunyasanon, N., Ounyoung, N., Loturat, H., Chaisri, N., & Mettripun, N. (2017). Musical chords transposer for captured image based on Optical Character Recognition. 2017 International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology (ICDAMT), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAMT.2017.7904923

Yannier, N., Hudson, S. E., Koedinger, K. R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Munakata, Y., Doebel, S., Schwartz, D. L., Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L., Callaghan, K., Theobald, E. J., Freeman, S., Cooper, K. M., & Brownell, S. E. (2021). Active learning: “Hands-on” meets “minds-on.” Science, 374(6563), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj9957