Ann Wang – Applied Science, Year 2

Abstract

Hydrogen fuel cells are increasingly recognized as a pivotal technology in the global transition to sustainable energy systems. Harnessing the potential of hydrogen, the element with the highest energy content per mass unit (142 MJ/kg), they are playing a critical role in decarbonizing industries that are hard to electrify, such as shipping and heavy manufacturing (Ursúa et al., 2012). However, currently, 96% of hydrogen gas is derived from fossil fuels, with only 4% generated via water electrolysis. Thus, scaling up green hydrogen production is critical to maintaining the sustainability of fuel cell technologies. This study investigates the efficiency of hydrogen production and the amount of corrosion induced by various electrolytes, including KOH, NaCl, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3, in Alkaline Water Electrolysis. At an electrolyte concentration of 1M, it was found that KOH had the fastest rate of hydrogen production at 2.4´10-5 ± 1´10-6 moles/second, followed by NaCl and Na2CO3, which showed similar rates at 1.4´10-5 ± 6´10-6 moles/second and 1.3´10-5 ± 3´10-6 moles/second respectively, and finally NaHCO3 with the lowest rate at 5.9 ´10-6 ± 3´10-6 moles/second. On the other hand, NaCl caused the most corrosion of electrodes, followed by KOH, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3 in that order.

Introduction

Alkaline Electrolysis Mechanism

Water electrolysis uses electricity to divide water into hydrogen and oxygen gas. The system involves two half-cell reactions at the cathode and anode compartments, respectively: the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (1) and the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (2) (Daodui and Bounahmidi., 2023).

Alkaline Water Electrolysis (AWE) is a popular type of water electrolysis that uses a basic solution as the electrolyte. Commonly implemented for its robustness and reliability, AWE requires the lowest operational temperature while maintaining the highest tolerance for impurities in the water when compared to other electrolysis techniques such as Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) and Solid Oxide Electrolysis (SOE) (Becker et al., 2023).

Variables Impacting Hydrogen Production

For Alkaline Water Electrolysis to outcompete fossil fuels, its cost needs to decrease from 3-6 USD/kgH2 to 2 USD/kgH2, and its efficiency needs to improve from 50-60 kWh/kgH2 to 40-45 kWh/kgH2 (Franco and Giovannini., 2023). Thus, to further scale up green hydrogen production, many studies have been conducted to determine the optimal operating parameters of AWE in terms of hydrogen production rates, the resulting gas purity, and the amount of electrode corrosion.

I. Flow Rate

A popular model by Ulleberg (2013) describes that while a higher flow rate facilitates ion movement and reaction kinetics, it can reduce hydrogen purity due to the increased migration of dissolved species between half-cells; specifically, oxygen or other byproducts from the anode are more likely to mix with the hydrogen gas produced at the cathode. From another perspective, Xue (2016) studied specific flow patterns, and concluded that achieving uniform flow patterns can prevent gas bubble accumulation and increase hydrogen production by 22%.

II. Electrode Properties

Hreiz et al. (2015) found that shorter inter-electrode distances and increased surface area of electrodes enhance current density and hydrogen generation. On the other hand, electrode roughness promotes gas bubble entrapment which can lead to elevated overpotentials, where unwanted redox reactions at the anode, like the oxidation of chlorine gas instead of oxygen gas, are favoured (Chaplin, 2022). Accordingly, more heat is generated and a loss in efficiency occurs.

III. Temperature

Elevated temperatures positively enhance electrolyte conductivity and HER/OER reaction rates, but also increase overpotential effects, bubble size, gas crossover, which negatively impacts the hydrogen purity (Jang et al., 2021; Hammoudi et al., 2012).

IV. Pressure

Regarding the impact of pressure, research by Sanchez et al. (2018) revealed that while increased pressure raises the total voltage required, it also results in reduced bubble diameter, which decreases electrolyte resistance and thus indirectly lowers cell voltage. Overall, pressure increases have a negative non-linear impact on the efficiency of electrolysis, although the effect is minimal compared to other factors.

V. Concentration of Electrolyte

Increasing the electrolyte concentration within an optimal range can improve electrolyte conductivity, decrease gas solubility, and enhance hydrogen purity by facilitating efficient ion transport and reaction kinetics (Amores et al., 2014; Haug et al., 2017) However, concentrations that exceed the optimal threshold (~6.5M) may hinder conductivity due to ionic saturation and accelerate corrosion of the electrodes.

VI. Electrolytes

As evident through sections I-V, there are many factors that influence the efficiency of Alkaline Water Electrolysis; this study focuses specifically on the types of electrolytes and their impact on the rate of hydrogen production and corrosion, which are two factors that, to the author’s knowledge, have not been investigated comprehensively together for the selected electrolytes.

An ideal electrolyte for water electrolysis should have high ionic conductivity to efficiently conduct ions between the cathode and anode, enabling hydroxide ions produced in the HER reaction at the cathode to migrate to the anode for the OER reaction to occur (Han et al., 2020). Similarly, having OH⁻ ions already in solution facilitates the OER reaction at the anode. Additional considerations include the amount of electrode corrosion caused by the electrolyte, environmental impacts of the byproducts, and potential production of chlorine gas through overpotential effects.

Currently, potassium hydroxide (KOH) is commonly used in Alkaline Electrolysis due to the high ionic conductivity of K+ ions and strong basic qualities. However, KOH is highly caustic and can cause significant corrosion to the materials used in electrodes, especially over long-term use (Basori et al., 2023). Additionally, improper handling or disposal of KOH can have detrimental environmental effects, such as soil degradation and contamination of water sources. Therefore, this paper intends to explore the use of safer and more sustainable electrolytes in AWE electrolysis. The alternative electrolytes investigated were NaCl, which has a high ionic conductivity; NaHCO3 because of its accessibility, basic properties, and minimal harmful byproducts; and Na2CO3, for similar reasons as NaHCO3.

It was hypothesized that KOH would demonstrate the most effective electrolysis performance, followed by NaCl, Na2CO3,and NaHCO3 in that order, as ion movement is facilitated with increased conductivity (Yuan et al., 2024). On the other hand, the amounts of corrosion for NaCl, Na2CO3,and NaHCO3 were predicted to be lower than KOH because being a strong base, KOH is more reactive with metals (New Jersey Department of Health, 2010). Therefore, whether the electrolyte was optimal for AWE was evaluated based on the rate of hydrogen production and the amount corrosion observed.

Methodology

Prototype Building

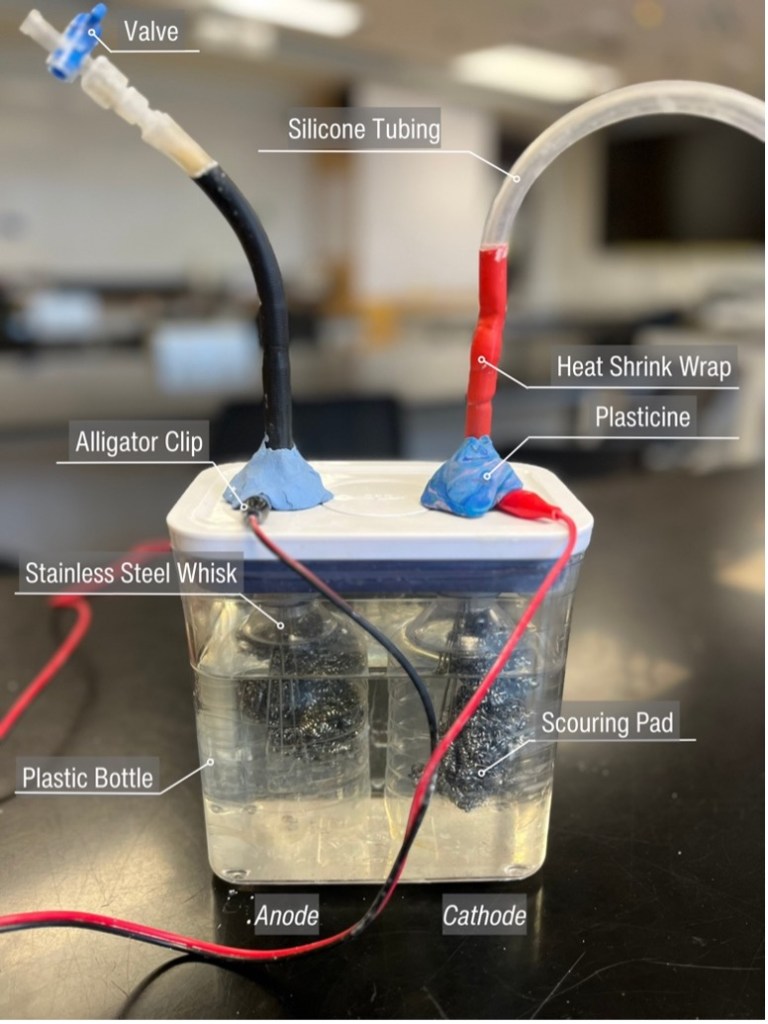

In this study, an electrolyser, inspired by a design by Ben Cusick (2021), was constructed to generate hydrogen. A 1.6L container with an airtight lid (Oxo) was used as the electrolysis chamber. Two holes with a diameter of 3/8” (0.9525cm) were drilled into the lid with the centre of each hole positioned 4.0cm from the side edge and 5.25cm from the top edge.

Stainless steel whisks with hollow handles (Anaeat) were used as electrodes, and scouring pads (Cdskba) were inserted into the wire end of the whisk to increase the surface area. To prevent the mixing of H2 and O2 gas while permitting the migration of ions in solutions, plastic bottles (500mL) with 6cm cut of the bottom were used to separate the cathode and anode.

Finally, to ensure that the apparatus was airtight, the coiled whisk handles were sealed with heat shrink plastic in the section where they passed through the lid and around the connection to the silicon tubing that allowed the H2 to flow into the eudiometer. Modelling clay was used to seal the area around the alligator clips attached to the unsealed area of the whisk handles, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Orthographic projection of electrolyser (top view, front view, and side view) with specific dimensions

Figure 2. Electrolyser prototype with materials labelled.

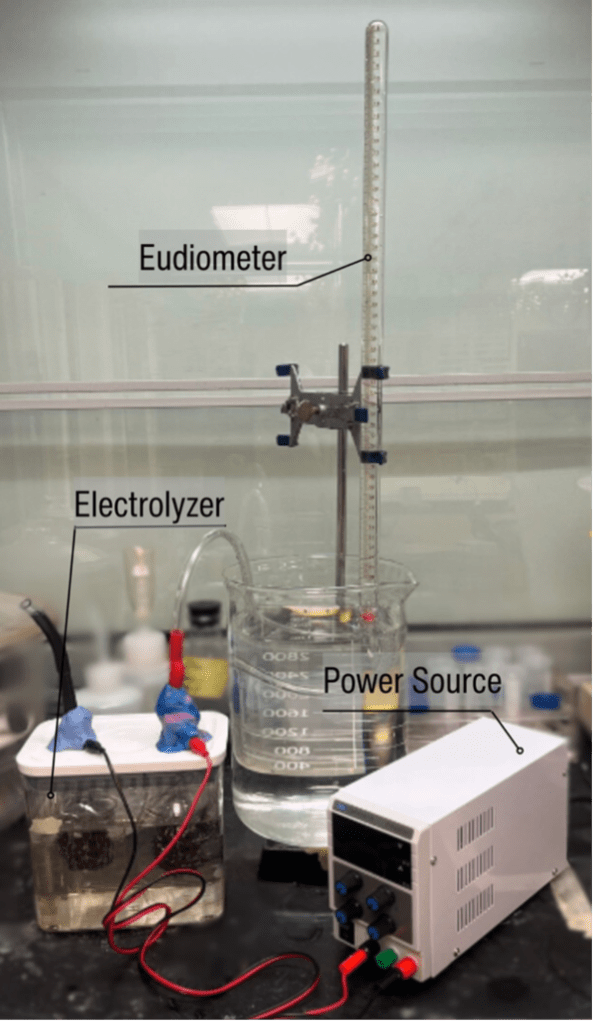

Figure 3. Experimental setup consisting of the power source, electrolyser and eudiometer.

Data Collection

To prepare the solution, 1.2 moles of the desired electrolyte were added to 1.2 L of distilled water to create a 1 M solution in the container, which was stirred until no solid particles remained. The power supply (Sky Toppower STP6005H) was set up at a constant voltage of 29V with the positive terminal attached to the oxygen-producing side (black tubing) and the negative terminal attached to hydrogen-producing side (red tubing). To determine the amount of gas produced, a eudiometer was used. Specifically, when the first gas discharge occurred, the time elapsed, the volume of gas in the eudiometer tube, and the height of the water column were recorded. Five tests were conducted for each electrolyte, with the exception of KOH, where three tests were conducted because of supply limitations. Between each test, the solution of electrolyte was replaced, and the apparatus was rinsed with distilled water; between each electrolyte, the plastic bottles and scouring pads were replaced.

Results

Qualitative Observations and Pictures

Raw Data

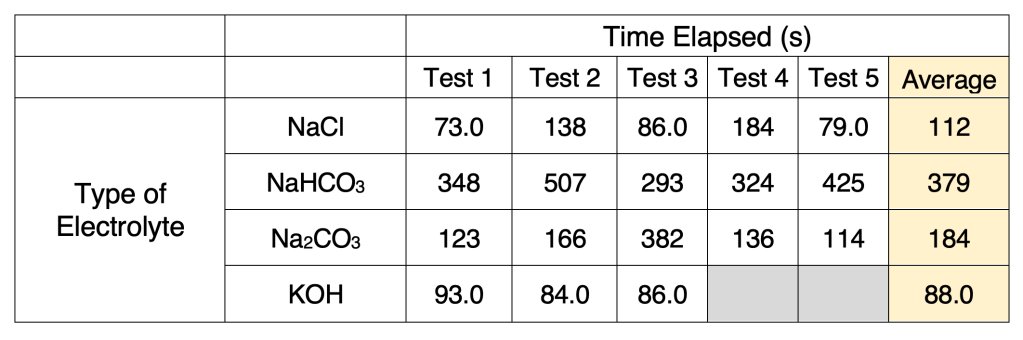

Table 1. Time elapsed at the first gas discharge

Table 2. Volume of gas in eudiometer at the first gas discharge

Table 3. Height of water column measured at the first gas discharge from the surface of the water in hydraulic trough to the meniscus of the water in the eudiometer.

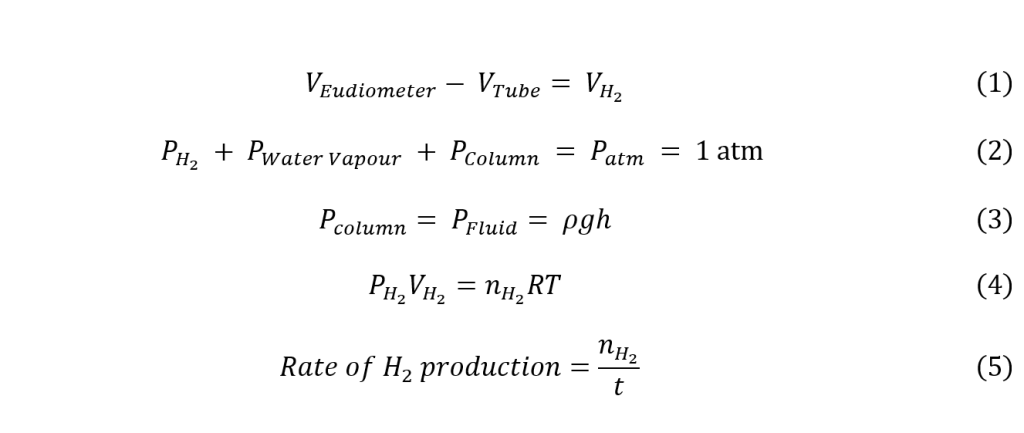

Calculations

To find the rate of hydrogen production, the data collected above was used for a set of calculations. Firstly, to account for the pre-existing gasses in the apparatus tube and determine the actual volume of H2 in the eudiometer, equation (1) was used. Then, the actual pressure of the H2 was calculated with equation (2), considering the pressure of the water column in the eudiometer as determined in equation (3). Finally, the rate of hydrogen production in moles H2/second was calculated by taking the number of moles of hydrogen calculated with the ideal gas law (4) and dividing it by the time elapsed (5). These calculations were carried out using a surface air pressure of 1 atm, a temperature of 293.15 K inside the eudiometer, and a water vapor pressure of 2411 Pa (National Weather Service, n.d.).

Table 4. Sample calculation of process described above with data from the first test with the electrolyte KOH

Data after Calculations

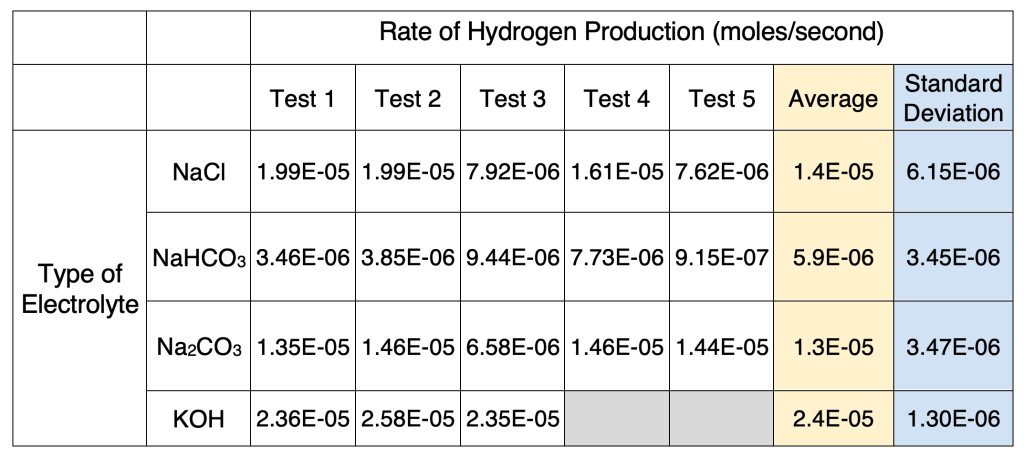

Table 5. Calculated rates of hydrogen production

According to the calculated graph shown in Figure 9, KOH showed the fastest rate of hydrogen gas production, followed by NaCl, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3.

Figure 9. Bar graph of average rates of hydrogen production with error bars

Statistical Test Results

To determine if the differences between the rates of hydrogen production of the electrolytes are statistically significant, four two-sample t-tests were conducted at an alpha value of 0.05. It was determined with a 95% confidence level that there was a significant difference between KOH and NaCl (p = 0.0199), NaCl and NaHCO3 (p = 0.025), and Na2CO3 and NaHCO3 (p = 0.0083). On the other hand, there was no statistical difference between NaCl and Na2CO3 (p = 0.63).

Discussion

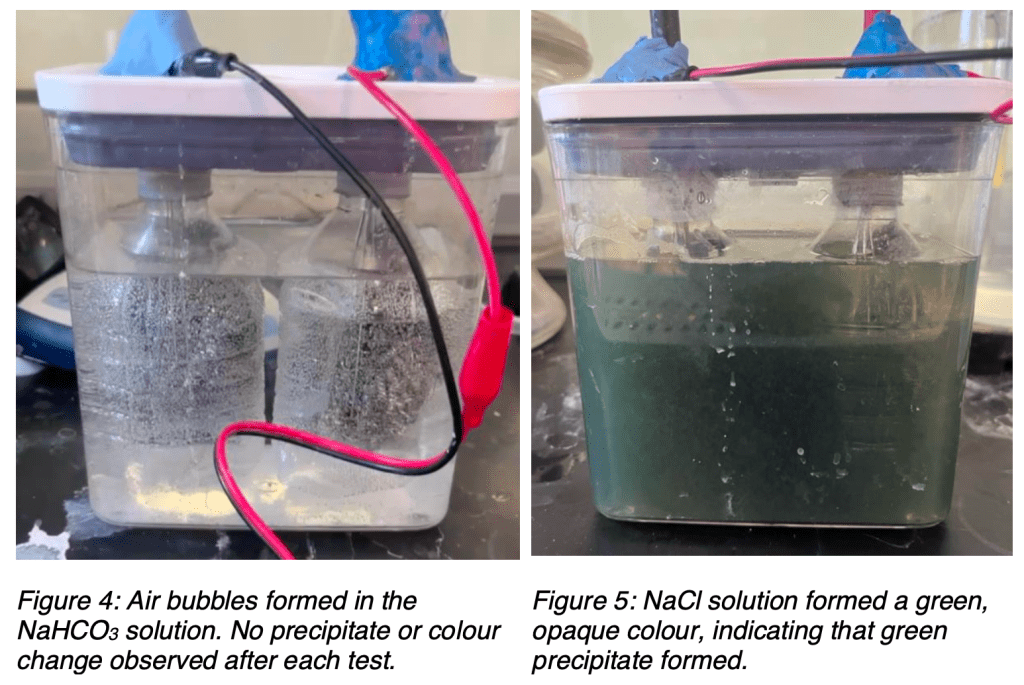

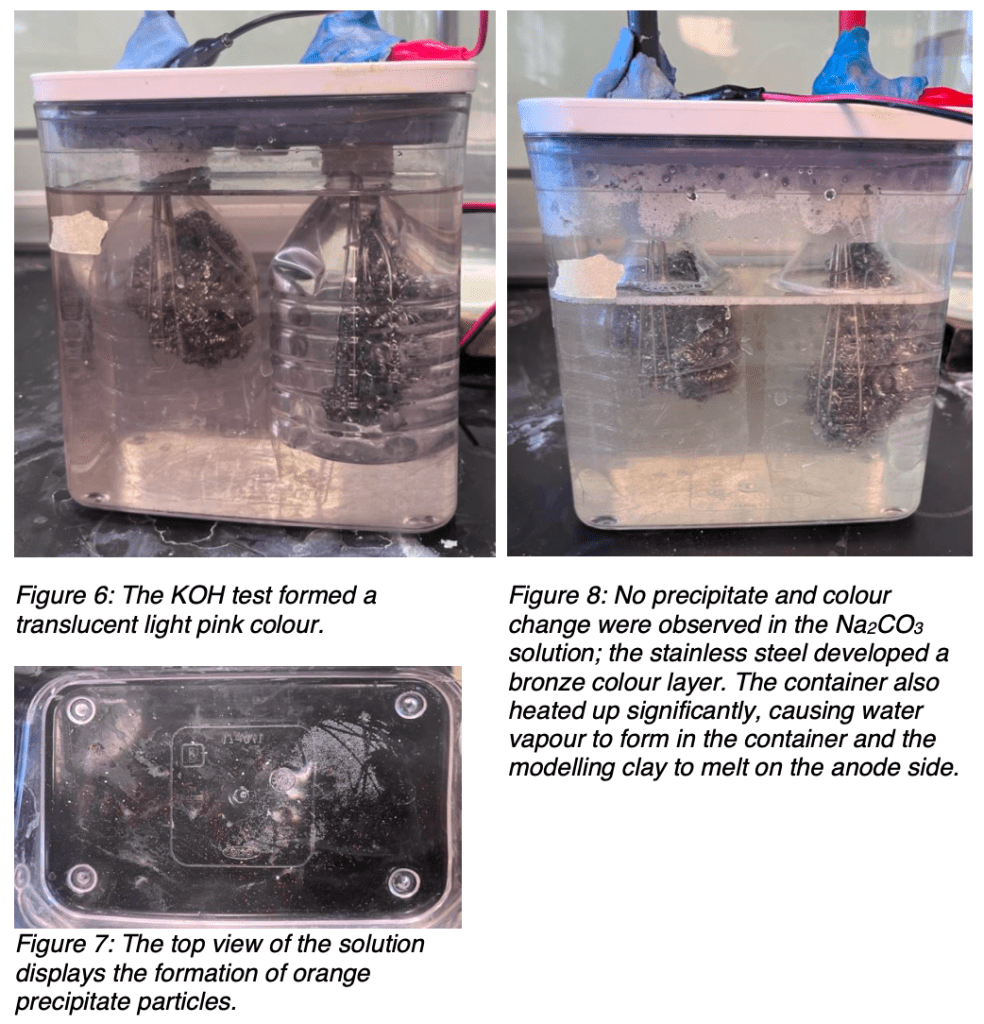

Given the same input voltage, we can conclude that KOH was the electrolyte with the highest rate of hydrogen production, and thus was the most efficient, followed by NaCl and Na2CO3, which were statistically equivalent, and finally NaHCO3. In terms of corrosion, it was observed that NaCl displayed the most corrosion, followed by KOH, Na2CO3, and NaHCO3 in that order.

I. Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

Among the tested solutions, KOH exhibited the highest hydrogen production rate (0.025 moles/second), which can be attributed to its high ionic conductivity and its strong basic qualities. However, as apparent in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the solution developed a translucent pink colour and formed orange precipitate, which is likely from the creation of iron (III) hydroxide (Fe(OH)3) precipitate, an indication of corrosion to the stainless-steel electrodes. Thus, a future investigation could comprise of testing other affordable electrolyte materials, like graphite and copper, in a solution of KOH for resistance to alkaline corrosion.

II. Sodium Chloride (NaCl)

Sodium chloride (NaCl) showed the second highest hydrogen production rate along with Na2CO3, suggesting that it supports electrolysis reasonably well. However, because of the lower overpotential of chlorine gas when compared to oxygen gas, chlorine gas formed at the cathode, reacting with water to produce HCl (Wang et al., 2025). This Cl– oxidation of chromium formed CrCl3, breaking down the protective oxide layer on stainless-steel electrodes and accelerating corrosion, as shown in Figure 5. Therefore, minimizing the overpotential effect at the cathode is essential for improving NaCl as an electrolyte in alkaline electrolysis.

III. Sodium Carbonate (Na2CO3)

Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) produced hydrogen at a similar rate compared to NaCl, despite its lower ionic conductivity. This could be because carbonate ions (CO32-) can undergo hydrolysis (CO32⁻(aq) + H2O(l) ⇋ HCO3– + OH– // Kb = 1.79×10-4), facilitating the migration of OH– ions from the anode to the cathode and thus the redox reaction. Moreover, carbonate can also react with iron from the electrodes to form a precipitate (CO32-(aq) + Fe2+(aq) → FeCO3(s)), which was observed through the bronze-coloured layer on the electrodes in figure 8. According to Neerup (2023), when FeCO3 is obtained as a byproduct of corrosion, it can create a protective barrier against further corrosion. In the industry, FeCO3 can be used as an iron source for producing animal feed, as a soil stabilizer in agriculture, and as a potential anode material in lithium batteries. Thus, future research could explore the dual production of FeCO3 and hydrogen gas using Na2CO3 in AWE.

IV. Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO3)

Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) had the lowest hydrogen production, which can be linked to its weak ionization and decomposition into CO2. Specifically, the equilibrium constant for the equation CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3 is very low, (Keq = 1.70 × 10-3 at 25°C); thus, NaHCO3, when dissolved in water, spontaneously forms carbon dioxide, as apparent in Figure 4, further limiting proton availability for hydrogen formation. While minimal corrosion was observed, this spontaneous decomposition suggests that sodium bicarbonate may be less effective as an electrolyte for AWE.

Limitations When Selecting Electrolytes

In this experiment, two limitations were encountered when choosing electrolytes to investigate: current constraints on the power source and the molar solubility. For example, for Calcium Chloride (CaCl2) and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), ~22V was the highest voltage the power source could be set to without switching to a constant current setting, indicating that the solution was drawing more current than the amount of current the power source could operate (5A). To mitigate this issue in the future, a power source with a maximum current of 10A should be used or the set voltage for testing should be lowered. Next, the low solubility of Borax/Sodium tetraborate decahydrate (Na2 [B4O5(OH)4]·8H2O (31.7 g/L or 0.083M) prevented it from reaching the concentration used for other salts (1M) under standard conditions. To allow them to be comparable with higher soluble electrolytes in future experiments, the set molarity should be lowered.

Other Potential Errors

Several factors, including voltage fluctuations, potential gas contamination, asymmetry of scouring pads in electrodes, and temperature changes, may have influenced the accuracy and consistency of the hydrogen production rate in this experiment. Primarily, slight fluctuations in voltage during testing may have affected the rate of hydrogen production, as a higher voltage increases the electrolysis rate. Additionally, the possibility of other gases entering the collection tube alongside hydrogen could have impacted the purity of the collected gas, leading to potential overestimations in volume measurements. Moreover, when inserted into the whisks, the scouring pads were not perfectly even on all sides, which could have potentially resulted in inconsistent surface area when they were replaced between electrolytes. Another factor to consider is that the temperature inside the electrolysis cell may have increased over time as the apparatus continued running. Since higher temperatures generally enhance reaction rates by increasing ion mobility, this could have contributed to higher hydrogen production rate for electrolytes with a higher resistance and exothermic properties (Na2CO3).

Future Direction

Moving forward, future research could explore mixed electrolyte systems by combining multiple electrolytes to optimize conductivity and efficiency. Moreover, weighing the electrodes before and after the experiment would be valuable to obtain quantitative measurements of the amount of corrosion. Further investigation into methods for reducing overpotential effects would enhance the durability of a system using NaCl as an electrolyte. Additionally, exploring the potential reuse of byproducts, such as using FeCO₃ as a corrosion inhibitor, would be valuable. Finally, observing how the hydrogen production rate changes over time as the reaction progresses could provide a deeper understanding of long-term electrolysis performance.

Beyond energy storage and transportation, hydrogen technology is being developed in many other fields to decarbonize material and energy production. For example, a variation of the alkaline electrolyser can be used to generate concrete at a significantly lower carbon footprint and increase the rate of reactive carbon capture (Xie et al., 2023; Berlinguette Group UBC, 2025). Additionally, it has been shown that the rate of nuclear fusion can be increased by loading the reactor with high concentrations of hydrogen.

The above initiatives have been demonstrated with small-scale models and prototypes; however, they have yet to enter the industry. Thus, future projects could investigate the scalability and cost effectiveness of these technologies.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that potassium hydroxide (KOH) outperforms the other electrolytes in terms of hydrogen production efficiency in AWE, as anticipated due to its high ionic conductivity. However, the presence of byproducts from corrosion, such as Fe(OH)3, highlights challenges for the long-term use of KOH as an electrolyte. On the other hand, sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) emerged as a promising alternative, having minimal corrosion and offering the additional benefit of forming byproducts of industrial value, such as FeCO3. Furthermore, sodium chloride (NaCl) exhibited comparable hydrogen production rate to Na2CO3 but caused the most corrosion on the electrodes because of overpotential effects. Finally, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) had the lowest rate of hydrogen production but also had the least amount of corrosion on the electrodes. By identifying the advantages and drawbacks of each of these electrolytes, this study provides a more comprehensive picture of durability and efficiency in AWE and contributes to the development of other emerging hydrogen technologies.

References

Amores, E., Rodríguez, J., & Carreras, C. (2014). Influence of operation parameters in the modeling of alkaline water electrolyzers for hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 39(25), 13063–13078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.07.001

Basori, B., Mohamad, W. M. F. W., Mansor, M. R., Tamaldin, N., Iswandi, A., Ajiriyanto, M. K., & Susetyo, F. B. (2023). Effect of KOH concentration on corrosion behavior and surface morphology of stainless steel 316L for HHO generator application. Journal of Electrochemical Science and Engineering. https://doi.org/10.5599/jese.1615

Becker, H., Murawski, J., Shinde, D. V., Stephens, I. E. L., Hinds, G., & Smith, G. (2023). Impact of impurities on water electrolysis: a review. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 7(7), 1565–1603. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2se01517j

Berlinguette Group UBC. (2024, November 28). Carbon-neutral building materials [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bNuLrE3xjuo

Berlinguette Group UBC. (2023, February 28). Advanced nuclear fusion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzApRZYKGyY

Emam, A. S., Hamdan, M. O., Abu-Nabah, B. A., & Elnajjar, E. (2024). A review on recent trends, challenges, and innovations in alkaline water electrolysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 64, 599–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.03.238

El-Shafie, M. (2023). Hydrogen production by water electrolysis technologies: A review. Results in Engineering, 20, 101426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101426

Franco, A., & Giovannini, C. (2023). Recent and Future Advances in Water Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Generation: Critical Analysis and Perspectives. Sustainability, 15(24), 16917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416917

Han, C., Li, W., Liu, H. K., Dou, S., & Wang, J. (2020). Principals and strategies for constructing a highly reversible zinc metal anode in aqueous batteries. Nano Energy, 74, 104880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104880

Hammoudi, M., Henao, C., Agbossou, K., Dubé, Y., & Doumbia, M. (2012). New multi-physics approach for modelling and design of alkaline electrolyzers. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37(19), 13895–13913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.07.015

Haug, P., Kreitz, B., Koj, M., & Turek, T. (2017). Process modelling of an alkaline water electrolyzer. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 42(24), 15689–15707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.05.031

Hreiz, R., Abdelouahed, L., Fünfschilling, D., & Lapicque, F. (2015). Electrogenerated bubbles induced convection in narrow vertical cells: PIV measurements and Euler–Lagrange CFD simulation. Chemical Engineering Science, 134, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2015.04.041

Jang, D., Cho, H., & Kang, S. (2021). Numerical modeling and analysis of the effect of pressure on the performance of an alkaline water electrolysis system. Applied Energy, 287, 116554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116554

NOAA’s National Weather Service. (n.d.). Vapor pressure calculator. https://www.weather.gov/epz/wxcalc_vaporpressure

Neerup, R., Løge, I. A., & Fosbøl, P. L. (2023). FECO3 synthesis pathways: the influence of temperature, duration, and pressure. ACS Omega, 8(3), 3404–3414. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07303

New Jersey Department of Health. (2001). Right to know Hazardous substance fact sheet: POTASSIUM HYDROXIDE. https://nj.gov/health/eoh/rtkweb/documents/fs/1571.pdf

[NightHawkInLight]. (2021). DIY Hydrogen/Oxygen Generators From Grocery Store Items (HHO Fuel Cells & Split Cell Electrolysis) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d85OX6yEwE0&t=1744s

Sánchez, M., Amores, E., Rodríguez, L., & Clemente-Jul, C. (2018). Semi-empirical model and experimental validation for the performance evaluation of a 15 kW alkaline water electrolyzer. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 43(45), 20332–20345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.09.029

Spreafico, C. (2024). Prospective life cycle assessment to support eco-design of solid oxide fuel cells. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2024.2355899

Ulleberg, O. (2002). Modeling of advanced alkaline electrolyzers: a system simulation approach. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 28(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3199(02)00033-2

Ursúa, A., & Sanchis, P. (2012). Static–dynamic modelling of the electrical behaviour of a commercial advanced alkaline water electrolyser. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37(24), 18598–18614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.09.125

Wang, Y., Qu, G., Zhang, Y., Li, L., Wang, J., Lu, P., Ren, Y., Cheng, M., Cai, Y., & Li, J. (2025). Efficient and stable chlorine evolution reaction in a neutral environment using a low-ruthenium-doped CuMnRu/CC electrode. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 112, 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.02.417

Xie, Q., Wan, L., Zhang, Z., & Luo, J. (2023). Electrochemical transformation of limestone into calcium hydroxide and valuable carbonaceous products for decarbonizing cement production. iScience, 26(2), 106015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106015

Xue, L., Song, S., Chen, W., Liu, B., & Wang, X. (2024). Enhancing Efficiency in Alkaline Electrolysis Cells: Optimizing Flow Channels through Multiphase Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling. Energies, 17(2), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17020448

Yuan, Z., Chen, A., Liao, J., Song, L., & Zhou, X. (2023). Recent advances in multifunctional generalized local high-concentration electrolytes for high-efficiency alkali metal batteries. Nano Energy, 119, 109088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2023.109088