Yifan Zhuo – Year 3 (Student)

Lauren Pugsley (Mentor)

Abstract

An increasing number of antibiotic issues, like antibiotic resistance and shortage, have emerged all over the world, causing inconvenience and negative impacts on society. This study aims to compare the effectiveness of Urinary Tract Infection’s (UTI) home remedies with commonly used antibiotics in impeding bacterial motility, the main cause of UTI. It was observed that the bearberry leaf extract was more effective at disrupting bacterial motility than garlic extract, but less effective than fosfomycin. Additionally, in two out of three trials, the bacterial motility area in garlic extract was larger than without treatment, suggesting that garlic extract’s interaction with semi-solid agar might promote bacterial motility. It is suggested that further studies should be conducted, testing more home remedies with various volumes and the possible interaction between garlic extract and semi-solid agar.

Introduction

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) is an infection caused by bacteria invasion and growth in the urinary tract, which is composed of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra (Barber et al., 2013). As the second most common infectious disease, UTI affects more than 150 million people all over the world annually (Mlugu et al., 2023). If left untreated, severe UTI can lead to urosepsis, a systemic inflammatory response to infections in the urinary tract, which can be associated with multi-organ dysfunction and has a mortality rate of 25% to 60% (Kalra & Raizada, 2009; Peach et al., 2016; Porat et al., 2024). The global burden of UTIs has been increasing over the past few decades, with the absolute number of UTI cases rising by 60.40% from 1990 to 2019 (X. Yang et al., 2022).

Most infections involve infections of the lower urinary tract, which include the bladder and urethra (Mayo Clinic, 2022). UTI typically occurs when bacteria, most commonly Escherichia coli (E. coli), enter the urinary tract through the urethra and begin to spread in the bladder (Komala & Kumar, 2013). Nearly 95% of cases of UTIs are caused by bacteria that typically multiply at the opening of the urethra and travel up to the bladder (Flores-Mireles et al., 2015; Mount Sinai, n.d.). Although the urinary system is designed to keep out bacteria, the defenses sometimes fail, and bacteria may grow into a full-blown infection in the urinary tract (Mayo Clinic, 2022). The most common UTIs occur mainly in women because they have a shorter urethra than men do, and thus, the bacteria need to travel less distance to reach the bladder in females (Czajkowski et al., 2021). In fact, about 50-60% of adult women experience at least one UTI in their lifetime (Al-Badr & Al-Shaikh, 2013).

To mitigate UTI, consuming bacteria-fighting antibiotics to the full recommended amount is the most usual and effective treatment (National Institutes of Health, 2022). There are several commonly used antibiotics to treat UTI, including Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, amoxicillin, and cephalexin (Jancel & Dudas, 2002). However, there has been constant threat of antibiotic drug shortages in countries of all income levels (Pandey et al., 2024). Between 2022 and 2023, Canada experienced shortages of antibiotics, including amoxicillin and cephalexin commonly used for UTI treatment (Government of Canada, 2023).

Despite being a pressing and severe infection affecting millions of people annually, research on UTIs and potential treatments is slowed because it requires the use of infected specimens (Little et al., 2006; Sinawe & Casadesus, 2024). The obtainment of such materials is difficult and can be time-consuming, and therefore slows down advancement and improvement in the field (Glogowska et al., 2023). Moreover, collecting infected samples like urine culture poses a slight risk of infection through methods like the utilization of needles (Cleveland Clinic, n.d.).

The inaccessibility of antibiotics and difficulty to obtain infected specimens prompted our study. Our study compared the effectiveness of antibiotics with more accessible and relatively cheaper UTI home remedies in impeding the E. coli’s movement in the urinary tract.

E. coli’s flagellum-mediated motility has been suggested to assist its dissemination to the upper urinary tract, thus causing infections (Lane et al., 2005, 2007). E. coli’s motility can be observed and analyzed when grown in semi-solid agar, which has a lower agar concentration of 0.2 to 0.5% and provides a soft, jelly-like growth medium for bacteria (Abdulkadieva et al., 2022; Millipore Sigma, n.d.). Our study performed a bacterial motility test, using 0.5% semi-solid agar plates to inoculate E. coli and observe the E. coli movement in the agar. Three treatments were tested in the study: fosfomycin antibiotics, garlic extract, and bearberry leaves supplement, with the latter two being typical UTI home remedies that maintain antimicrobial properties (Chang et al., 2022; Michel, 2024). Treatments were added into the agar in recorded volumes prior to agar solidification. The area of the bacteria grown on the plates were compared and analyzed to infer the bacterial movement and effectiveness of the treatments in impeding bacterial motility.

Materials and Methods

Semi-Solid Agar with Treatments Preparation

In 100 mL distilled water, 1 g tryptone, 0.5 g sodium chloride, and 0.5 g agar were suspended. The medium was boiled for complete dissolution and then sterilized in a 15 psi pressure cooker (All American) for 20 minutes. When cooled to approximately 50 °C, the treatments were added into the agar. For each 100 mL agar, 32 μL of 25 mg/mL fosfomycin stock solution (0.25 g fosfomycin (BioShop) dissolved in 10 mL distilled water), 2 garlic extract soft gels (Nature’s Bounty) (equivalent to 2000 mg of fresh garlic), or the powder within 1 bearberry leaves supplement capsule (Nature’s Way) (containing 370 mg of bearberry leaf) was added for each treatment group respectively. The agar was poured into sterile Petri dishes and allowed to set with lid overnight.

Liquid Culture Incubation

To a sterile culture tube, 5 mL of Lennox Broth liquid broth (Carolina) was added. One E. coli colony was picked up from a source plate with a pipette tip. The culture tube was tilted, allowing the pipette tip to touch the side of the tube for colony cell transfer. The broth was pipetted up and down to mix. A control tube with no transferred bacteria was also made to ensure good aseptic technique. The culture tubes were incubated overnight at 37 °C with a constant horizontal shaking speed of 225 rpm.

E. coli Inoculation

Using a pipette, 2 μL of the liquid culture was inoculated into the center of the semi-solid agar plate. The loaded sterile tip was pushed into the agar and the contents were gently expelled before being pulled up. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours.

E. coli Motility Analysis using ImageJ

Following incubation, pictures of each plate were taken, where the bases of the plates were visible. Each picture was opened in the software ImageJ. The Oval tool was used to locate the base of the plate, and the Straight Line tool was used to mark the diameter of the base. The scale of the picture was set as shown in Figure 1: the marked diameter was entered as the reference distance in pixels, and 5.5 cm, the measured diameter of the plate, was set as the known distance.

Figure 1. Example image where the diameter of the plate was marked, and the scale was set to known distance of 5.5 cm.

The image was then smoothed three times and converted to 8-bit in the software, assisting the threshold adjustment later on. Then, the threshold was adjusted as shown in Figure 2: the dark background was selected, the upper threshold level was maintained at 255, and the lower threshold was adjusted to let the red shade in the image match the outline of the E. coli motility.

Figure 2. Example image where the threshold was adjusted so that the red shade approximately matched the outline of the bacterial motility.

Finally, the Analyze Particles tool was used to approximate the area of the E. coli motility on the plate, showing the labeled particles of the image and a table of their corresponding area as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Example image’s labeled particles and their corresponding area, approximated by the software.

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s Range Test

Using XLMiner Analysis ToolPak in Google Sheets, the one-way ANOVA test was performed on measured bacterial motility areas in each of the three trials. The p-value from the ANOVA test output indicated that the difference in areas between treatment groups were significantly different. However, it was unknown which groups contributed to this significant difference, and therefore, Tukey’s Range Test was necessarily performed.

A table was set up to list the treatment groups in distinct pairs. The absolute values of the difference in the mean areas of each pair were calculated and recorded. The standard error was also calculated for each pair, using formula 1:

where MSE is the mean square error found in the MS column and Within Groups row of the ANOVA result, and nj is the sample size from each group, which is 3 in this study. Then, the q score was calculated for each of the pairs, using formula 2:

Finally, the calculated qtukey scores were compared with the critical level for the given number of groups and degree of freedom. In this study, there were four treatment groups and a degree of freedom of 8 according to ANOVA results, and therefore, the critical level of 5% significance level was 4.529. When the qtukey score was greater than the 4.529 critical level, the pair of treatment groups had a significant difference. When the qtukey score was smaller than the 4.529 critical level, the pair of treatment groups did not have a significant difference.

Results

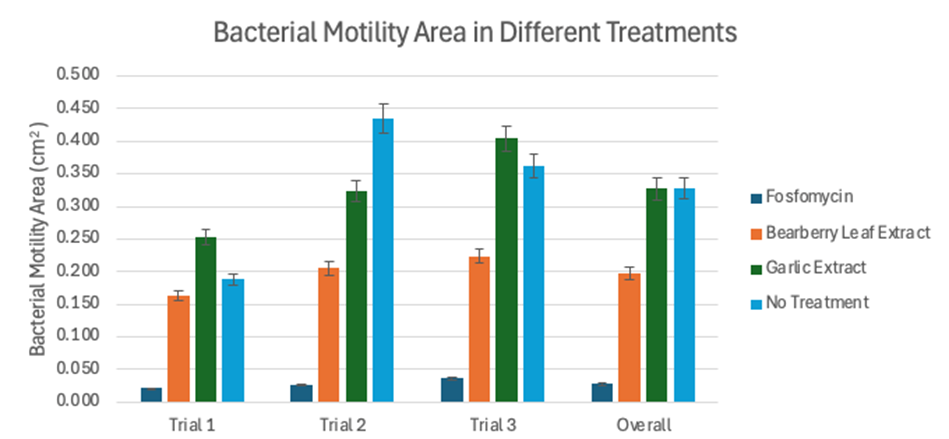

Overall, three trials were conducted, with three plates in each treatment group within these trials. However, only two plates were tested for garlic extract in trial 2 due to contamination of the third plate. In addition to growth inside the agar, bacteria were observed to grow on the surface of the agar as well. The average area and fold change of the E. coli motility was calculated for each treatment compared to the bacteria area in the no treatment group. Using the E. coli’s average area from each of the three trials and the overall area, the overall area and fold change for each treatment were calculated and collected in Table 1, and a grouped bar graph was constructed as presented in Figure 1.

Table 1. Bacterial motility area (cm2) of each plate, treatment, and trial, and the fold change in area compared to fosfomycin of each trial.

Figure 1. Bacterial motility area (cm2) in different treatments in each trial and overall.

Using the E. coli’s average area from each trial, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the statistical significance of the difference in areas between treatment groups, as shown in Table 2. Then, Tukey’s Range Test was conducted using ANOVA results and average bacterial area to assess the significance of differences between pairs of treatment groups, as shown in Table 3.

Table 2. One-way ANOVA results using average bacterial motility area in each trial

Table 3. Tukey’s Range Test results using ANOVA results and average bacterial motility area in each trial.

Overall, the bacterial motility areas in the no treatment and garlic extract groups were the largest, with a difference of 0.002 cm2. The garlic extract had a 1.006-fold decrease in motility compared to the no treatment group. However, since the error bars of the two average area overlapped as shown in Figure 1, the overall area difference might not be statistically significant. The bacterial motility in fosfomycin was the smallest, with an average motility area of 0.028 cm2 and a 11.750-fold decrease in motility compared to the control. The average bacterial motility in bearberry leaf extract was the second smallest, with an average area of 0.197 cm2 and a 1.670-fold decrease in motility. It’s also worth noting that the bacterial motility in garlic extract was even larger than the no treatment group in two out of the three trials.

The one-way ANOVA demonstrated that the difference observed in bacterial motility areas between treatment groups was significant [F(3, 8) = 10.625, p = 0.004]. Tukey’s Range Test showed that, more specifically, the differences observed in bacterial areas between fosfomycin and garlic extract, and fosfomycin and no treatment were statistically significant.

Discussion

According to the ANOVA results, the differences observed in terms of bacterial motility areas in different treatment groups were statistically significant and therefore unlikely to have occurred by chance alone. The observed differences in areas were therefore likely associated with the tested treatments. According to Tukey’s Range Test, due to the statistically significant difference in bacterial areas between fosfomycin and garlic extract, and fosfomycin and no treatment, garlic extract and no treatment likely could not impede bacterial growth and motility as much as fosfomycin. In comparison, the difference in bacterial areas between fosfomycin and bearberry leaf extract was not statistically significant, suggesting that the observed difference might be caused by chance, and bearberry leaf extract might be able to impede bacterial growth and motility to a similar degree as fosfomycin.

While the bacterial motility area for bearberry leaf extract groups was still larger than fosfomycin, it was consistently smaller than the bacterial motility area of the no treatment group. In comparison, in two out of three trials, the bacterial motility area in garlic extract was larger than without treatment. The results indicated that among the three UTI treatments tested, fosfomycin was suggested to be the most effective in impeding bacterial motility. Of the UTI home remedies tested, bearberry leaf extract was suggested to be more effective in disrupting bacterial motility than the garlic extract. The results, showing small differences between the bacterial motility area with garlic extract and without treatment, indicated that the garlic extract was not as effective or even promoted bacterial motility compared to no treatment, which differs from what has been commonly suggested in previous studies (Bhatwalkar et al., 2021; Nakamoto et al., 2020).

There are a few limitations of the experiment. Only two home remedies were chosen to be tested due to limited time and material. 2 μL of liquid culture was ejected into the agar instead of the optimal 1 μL due to the limited amount of fosfomycin, which might have contributed to the overflow and bacterial growth on the surface of the agar (Ravichandar et al., 2017). Therefore, the bacterial growth observed in the experiment might not be solely caused by E. coli’s motility. The powder within the bearberry leaves supplement capsule was not fully dissolved in the 0.5% semi-solid agar. The undissolved powder sedimented at the bottom of the plates, impeding a more comprehensive observation and analysis of the bacterial growth and movement in the agar with bearberry leaves treatment. The sediment at the bottom also resulted in ununiform treatment concentration in the agar, which might have impacted the bacterial growth. In the first trial, the incubator was accidentally set to be around 42 °C instead of the optimal growth temperature around 37 °C (Son & Taylor, 2021). Since the temperature exceeded 40 °C, E. coli’s growth might have been reduced, so the results obtained in the first trial were less comparable to the latter two trials (Yang et al., 2020). In the third trial, the liquid culture used for bacterial inoculation was initially grown with 1 colony in 10 mL broth, in comparison to 1 colony in 5 mL broth in the first two trials. The different bacterial concentration of the liquid culture used in the third trial might help explain the discrepancies of its bacterial motility area with the previous 2 trials.

In the future, the experiment should be repeated, including testing of more home remedies, such as kombucha and cranberry juice, and use of 1 μL liquid culture in each plate. Further study should be conducted with fully dissolved bearberry leaf powder in the agar to minimize the impact of incomplete dissolution on the bacterial growth. In addition, future studies should investigate the effect of home remedies’ volume on the bacteria growth to find the most effective way to apply the home remedy treatments. As for the analysis, the obtained bacterial growth was an approximation due to the limitation of the ImageJ software. In the future, more accurate measurement of the bacterial growth should be utilized, including the possible use of fluorescence microscopy (van Teeffelen et al., 2012).

In addition, our results showed that the bacterial motility area in the garlic extract in two out of three trials was larger than without treatment. The current methods of preparing garlic extract have several drawbacks that can affect the concentration of allicin, which is responsible for the antimicrobial activity in garlic. The use of acidic and alcoholic extractants could inhibit alliinase activity, which catalyzes the conversion of allicin from alliin (Nguyen et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2013). In addition, allicin is a volatile and unstable compound and could be lost to the atmosphere under high temperatures larger than 40 °C, which is usually the extraction temperature applied for 3 or more hours (Nguyen et al., 2021; Reiter et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2013). In fact, almost 90% of allicin can be lost within 3 hours of extraction under a temperature of over 40 °C (Nguyen et al., 2021). Therefore, our results point to an intriguing question that whether garlic extract promotes bacterial motility, contrary to the purpose of home remedies, or whether its interaction with semi-solid agar provides more ideal environment for bacteria growth and motility. These research questions have not been studied in existing literature to our knowledge and should be tested in future studies.

It is estimated that 5.7 million deaths occur each year, mostly in low- and middle-income countries, that could be prevented by antibiotics (Hartwig & Kliesow, 2020). UTI, an infection that could be treated by antibiotics, affects roughly 400 million people each year (Barron, 2024). Meanwhile, over 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur in the U.S. only, causing more than 35,000 deaths each year (CDC, 2025). These daunting estimations further highlight the importance of our finding that bearberry leaf extract could be a potentially effective alternative UTI treatment.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deep gratitude to my mentor Lauren Pugsley, who helped me finalize my methodology and provided constant support and suggestions throughout my entire project.

References

Abdulkadieva, M. M., Sysolyatina, E. V., Vasilieva, E. V., Gusarov, A. I., Domnin, P. A., Slonova, D. A., Stanishevskiy, Y. M., Vasiliev, M. M., Petrov, O. F., & Ermolaeva, S. A. (2022). Strain specific motility patterns and surface adhesion of virulent and probiotic Escherichia coli. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 614. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04592-y

Al-Badr, A., & Al-Shaikh, G. (2013). Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Management in Women. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 13(3), 359–367.

Barber, A. E., Norton, J. P., Spivak, A. M., & Mulvey, M. A. (2013). Urinary Tract Infections: Current and Emerging Management Strategies. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 57(5), 719–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit284

Barron, M. (2024, May 3). Why Do Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) Recur? ASM.Org. https://asm.org:443/Articles/2024/May/Why-Urinary-Tract-Infections-UTI-Recur

Bhatwalkar, S. B., Mondal, R., Krishna, S. B. N., Adam, J. K., Govender, P., & Anupam, R. (2021). Antibacterial Properties of Organosulfur Compounds of Garlic (Allium sativum). Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 613077. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.613077

CDC. (2025, April 11). 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report. Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html

Chang, Z., An, L., He, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, S., Lei, M., Xu, P., Lai, Y., Jiang, Z., Huang, Y., Duan, X., & Wu, W. (2022). Allicin suppressed Escherichia coli-induced urinary tract infections by a novel MALT1/NF-κB pathway. Food & Function, 13(6), 3495–3511. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1fo03853b

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). What Is a Urine Culture? Retrieved January 4, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/22126-urine-culture

Czajkowski, K., Broś-Konopielko, M., & Teliga-Czajkowska, J. (2021). Urinary tract infection in women. Przegla̜d Menopauzalny = Menopause Review, 20(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2021.105382

Flores-Mireles, A. L., Walker, J. N., Caparon, M., & Hultgren, S. J. (2015). Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 13(5), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3432

Glogowska, M., Croxson, C., Butler, C., & Hayward, G. (2023). Experiences of urine collection devices during suspected urinary tract infections: A qualitative study in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice, 73(732), e537–e544. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0491

Government of Canada. (2023, September 6). Supply of antibiotic oral suspension products: Notice [Notices]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-shortages/information-consumers/supply-notices/antibiotic-oral-suspension.html

Hartwig, R., & Kliesow, P. S. (2020). Antimicrobial Resistance between Lack of Access and Excess. https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/antimicrobial-resistance-between-lack-of-access-and-excess

Jancel, T., & Dudas, V. (2002). Management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Western Journal of Medicine, 176(1), 51–55.

Kalra, O. P., & Raizada, A. (2009). Approach to a Patient with Urosepsis. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases, 1(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-777X.52984

Komala, M., & Kumar, K. S. (2013). Urinary tract infection: causes, symptoms, diagnosis and it’s management. Indian Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Biotechnology, 1(2), 226. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289595790_Urinary_tract_infection_Causes_symptoms_diagnosis_and_it’s_management

Lane, M. C., Alteri, C. J., Smith, S. N., & Mobley, H. L. T. (2007). Expression of flagella is coincident with uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension to the upper urinary tract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(42), 16669–16674. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607898104

Lane, M. C., Lockatell, V., Monterosso, G., Lamphier, D., Weinert, J., Hebel, J. R., Johnson, D. E., & Mobley, H. L. T. (2005). Role of Motility in the Colonization of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the Urinary Tract. Infection and Immunity, 73(11), 7644–7656. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.73.11.7644-7656.2005

Little, P., Turner, S., Rumsby, K., Warner, G., Moore, M., Lowes, J. A., Smith, H., Hawke, C., & Mullee, M. (2006). Developing clinical rules to predict urinary tract infection in primary care settings: Sensitivity and specificity of near patient tests (dipsticks) and clinical scores. The British Journal of General Practice, 56(529), 606–612.

Mayo Clinic. (2022, September 14). Urinary tract infection (UTI)—Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/urinary-tract-infection/symptoms-causes/syc-20353447

Michel, K. (2024, June 5). Home Remedies for UTI. Comprehensive Urology. https://comprehensive-urology.com/urologist-desk/home-remedies-for-uti/

Millipore Sigma. (n.d.). Types of Media in Microbiology. Retrieved January 26, 2025, from https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/CA/en/technical-documents/technical-article/microbiological-testing/microbial-culture-media-preparation/types-of-media-in-microbiology

Mlugu, E. M., Mohamedi, J. A., Sangeda, R. Z., & Mwambete, K. D. (2023). Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of uropathogens with biofilm forming capacity among outpatients in morogoro, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 23(1), 660. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08641-x

Mount Sinai. (n.d.). Urinary tract infection Information. Mount Sinai Health System. Retrieved January 4, 2025, from https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/report/urinary-tract-infection

Nakamoto, M., Kunimura, K., Suzuki, J.-I., & Kodera, Y. (2020). Antimicrobial properties of hydrophobic compounds in garlic: Allicin, vinyldithiin, ajoene and diallyl polysulfides (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 19(2), 1550–1553. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2019.8388

National Institutes of Health. (2022, February 4). What are the treatments for UTIs & UI in women? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/urinary/conditioninfo/treatments

Nguyen, B. T., Hong, H. T., O’Hare, T. J., Wehr, J. B., Menzies, N. W., & Harper, S. M. (2021). A rapid and simplified methodology for the extraction and quantification of allicin in garlic. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 104, 104114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104114

Pandey, A. K., Cohn, J., Nampoothiri, V., Gadde, U., Ghataure, A., Kakkar, A. K., Gupta, Y., Kumar, Malhotra, S., Mbamalu, O., Mendelson, M., Märtson, A.-G., Singh, S., Tängdén, T., Shafiq, N., & Charani, E. (2024). A systematic review of antibiotic drug shortages and the strategies employed for managing these shortages. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2024.09.023

Peach, B. C., Garvan, G. J., Garvan, C. S., & Cimiotti, J. P. (2016). Risk Factors for Urosepsis in Older Adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 2, 2333721416638980. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721416638980

Porat, A., Bhutta, B. S., & Kesler, S. (2024). Urosepsis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482344/

Ravichandar, J. D., Bower, A. G., Julius, A. A., & Collins, C. H. (2017). Transcriptional control of motility enables directional movement of Escherichia coli in a signal gradient. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 8959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08870-6

Reiter, J., Levina, N., Van der Linden, M., Gruhlke, M., Martin, C., & Slusarenko, A. J. (2017). Diallylthiosulfinate (Allicin), a Volatile Antimicrobial from Garlic (Allium sativum), Kills Human Lung Pathogenic Bacteria, Including MDR Strains, as a Vapor. Molecules, 22(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22101711

Sinawe, H., & Casadesus, D. (2024). Urine Culture. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557569/

Son, M. S., & Taylor, R. K. (2021). Growth and Maintenance of Escherichia coli Laboratory Strains. Current Protocols, 1(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.20

van Teeffelen, S., Shaevitz, J. W., & Gitai, Z. (2012). Image analysis in fluorescence microscopy: Bacterial dynamics as a case study. BioEssays : News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, 34(5), 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201100148

Xu, J., Zhuang, Y., & Lao, F. (2013). Garlic oil soft capsules and preparation method thereof (China Patent CN103404851A). https://patents.google.com/patent/CN103404851A/en

Yang, C.-Y., Erickstad, M., Tadrist, L., Ronan, E., Gutierrez, E., Wong-Ng, J., & Groisman, A. (2020). Aggregation Temperature of Escherichia coli Depends on Steepness of the Thermal Gradient. Biophysical Journal, 118(11), 2816–2828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.02.033

Yang, X., Chen, H., Zheng, Y., Qu, S., Wang, H., & Yi, F. (2022). Disease burden and long-term trends of urinary tract infections: A worldwide report. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 888205. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.888205