Yixin (Sophie) Jiang – Year 3 (Student)

Vincent Wong (Mentor)

Abstract

Obstacle detection systems are vital for assistive technologies and autonomous navigation, particularly when deployed on everyday edge devices with limited computational resources. This study investigates whether quantization and pruning can enhance the efficiency of YOLOv8n, an object detection model, without significantly compromising its performance. Using a dataset of 3350 annotated public-space obstacle images across 22 classes, a baseline YOLOv8n model was trained and compared against four variant models: FP16 and INT8 quantized model, and 5% and 10% pruned models. All models were evaluated using a series of metrics: mAP scores, precision, recall, inference time, model size, and memory usage. Results suggested that quantization improved computational efficiency and inference time with minimal performance degradation; notably, the INT8 model reduced inference time by over 50% and cut model size by over 65% while preserving close-to-baseline performance. Pruning showed minimal computational benefit and caused more severe performance degradation. The findings highlight quantization, especially to INT8, as a robust strategy for enabling low-latency, accurate obstacle detection in resource-constrained environments such as assistive wearables, while pruning requires further refinement—such as architectural adaptation—to be similarly effective.

Introduction

Context

Obstacle detection plays a crucial role in various real-world applications, including autonomous vehicles, robotics, and assistive technologies (Alahdal et al., 2024; Anand et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). For visually impaired individuals, real-time obstacle detection systems offer the potential to significantly enhance independent mobility by providing timely alerts about road hazards. Traditional assistive tools such as canes or guide dogs are widely used, but they have limitations in detecting elevated or moving obstacles, and may be physically burdensome or financially inaccessible for some users (Lin & Wu, 2014; Merugu et al., 2022). Recent advances include GPS-based navigation aids and audio-feedback systems, yet many struggle with real-time inference speed and accuracy, or place cognitive or physical load placed on users (Dakopoulos & Bourbakis, 2010). These limitations highlight the need for compact, intelligent, and responsive systems capable of navigating dynamic environments. However, designing such systems presents unique challenges—not only must they be accurate and fast enough for real-time feedback, but they must also operate reliably on edge devices (such as Raspberry Pis) with limited computational power, memory, and energy.

Literature Review

Obstacle Detection and YOLO extensions: Obstacle detection using machine learning has seen significant advancements, especially since the introduction of deep learning (Boesch, 2024). The You Only Look Once (YOLO) model—first developed and introduced by Redmon et al. (2015)—differed from traditional detection pipelines that required multiple passes over each image for classification and instead offered a single-pass approach to multiple object detection that dramatically reduced inference while maintaining model performance. Since then, YOLO has undergone multiple iterations. Extensions of YOLO models, either equipped with modified architecture or fine tuned using new datasets, have shown promise in specialized domains, including autonomous vehicles (Alahdal et al., 2024), autonomous mobile robots (Anand et al., 2024), underwater object detection (Feng & Jin, 2024), and assistive technology (Wang et al., 2024). For assistive technology, specifically, Wang et al. (2024) developed YOLO-OD, aimed at aiding visually impaired individuals in outdoor environments. The study added several enhancements in YOLO’s architecture, such as a Feature Weighting Block for feature importance discrimination, to achieve an average precision of 30.02% on a public dataset.

Compact models: Given the computational demands of machine learning models, researchers have explored strategies for compacting these models for resource-constrained environments. Developed techniques includes: model quantization (Zhou et al., 2017; Han et al., 2016), where weights are stored with lower precision; pruning (Han et al., 2016; Molchanov et al., 2017), where insignificant or redundant aspects of a model are removed; Huffman coding (Han et al., 2016), where weights are compressed in a lossless manner to reduce storage requirement; and direct architecture modifications (Howard et al., 2017). Smaller YOLO variants, such as YOLOv8n (Ultralytics, n.d.-c), have been developed to strike a balance between performance and efficiency and for deployment on devices like Raspberry Pi. Nevertheless, these models still demand careful consideration of computational and storage resources in multi-model deployment scenarios where loading multiple models onto an edge device may exceed its capacity.

Research Focus

The central research question is: How can quantization and pruning strategies improve the efficiency of YOLO models for real-time obstacle detection on edge devices? Despite existing research on object detection and compact YOLO models, there is a significant gap in combining these research directions to optimize YOLO specifically for road obstacle (such as fences, gate barriers, potholes) detection in resource-constrained environments. While current small YOLO variants offer efficiency improvements, they may not yet be compact enough for future applications involving even smaller assistive devices or scenarios where multiple models compete for limited computational resources on devices like the Raspberry Pi. The present investigation seeks to address this gap by quantizing and pruning YOLOv8n to create YOLO model variants—then analyzing their performance and computational requirements. The findings aim to provide actionable insights into creating lightweight, adaptable YOLO configurations that are more computational efficient than YOLOv8n while maintaining high detection accuracy. They could inform the development of compact assistive technologies for the visually impaired, where real-time, reliable obstacle detection is critical, while also supporting broader applications in resource-limited environments.

Materials and Methods

Dataset and Base Model

The “Obstacles in Public Spaces for Dist-YOLO” dataset by Mufti Restu Mahesa (Mufti Restu Mahesa, 2024) was used. The dataset contains a curated collection of 3350 images capturing obstacles in public environments. There are a total of 22 obstacle classes: Right Turn, Left Turn, Puddle, Street Vendor, Obstacle, Bad Road, Garbage Bin, Chair, Pothole, Car, Motorcycle, Pedestrian, Fence, Gate barrier, Roadblock, Door, Tree, Plant pot, Drain, Stair, Pole, and Zebra Cross. Each image was annotated with bounding boxes indicating the location and class of obstacles (Figure 1). For the purpose of this study, the database was randomly split into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing sets. A custom YAML configuration file was generated to define the dataset structure and class labels to guide model training.

Figure 1. Sample labeled dataset.

The YOLOv8n (Ultralytics, n.d.-c), which is a lightweight object detection architecture pre-trained on the Common Objects in Context (COCO) dataset, was used as a base model. To best leverage transfer learning and ensure compatibility between the obstacle dataset and the pretrained weights, semantically similar classes in the obstacle dataset were mapped to corresponding COCO classes. Specifically, Pedestrian was mapped to Person; Motorcycle retained its label as Motorcycle; and Car retained its label as Car.

Baseline Model Training

YOLOv8n was trained with the training subset of the obstacle dataset using the Ultralytics library for 100 epochs with batch size 16 (Ultralytics, n.d.-b). The trained model was exported to a .engine format for later inference and deployment. This model served as the controlled baseline against the quantized and pruned YOLOv8n variants created in Sections 2.3 and 2.4.

Quantization

To investigate the effect of quantization on model performance and computational requirements, two levels of quantization were explored using Ultralytics.

The original YOLOv8n model was trained for 100 epochs with batch size 16 and with the Automatic Mixed Precision (amp = True) setting enabled (Ultralytics, n.d.-b). This allowed the model to automatically adjust between high (float32) and low (float 16) numeric precision during training. While training with automatic mixed precision does not quantize the model, it can indirectly train the model to be more tolerant of lower-precision environments, particularly for float16.

Then, the resulting trained model was exported in two precision. First, a model was exported in float16 precision to generate a FP16 model variant. Second, the model was exported in int8 precision for a INT8 model variant; throughout this export process, the validation dataset was used as a calibration set to ensure that the precision loss due to the quantization was minimized. Both exported models were in .engine format for consistency.

Pruning

The pruning process began with the trained baseline YOLOv8n model from Section 2.2. The goal was to simplify the model by removing filters that contribute the least to the model’s predictions. In this case, the least significant filters were assessed through the L1 norm, defined as the sum of the absolute values of a filter’s weights. A lower L1 norm often indicates that the given filter is redundant or underutilized. Looping through the model’s convolutional layers and using PyTorch’s prune.ln_structured with n=1 and dim=1 (PyTorch, 2023), the program pruned entire filters and any corresponding bias terms with the lowest L1 norms along the output channel. The pruning masks were then permanently removed to ensure that the pruning is absolute and that the model is truly simplified and compatible with exporters.

Two levels of pruning were tested: removing either 5% or 10% of the least significant filter channels and their associated biases from each convolutional layer. Following pruning, both model variants were retrained for 100 epochs on the training dataset to allow the model to adapt and recover some of the performance degradation. The retained pruned models were then exported to .engine format.

Evaluation Metrics

All models (baseline, FL16, INT8, 5% pruned, and 10% pruned model) were evaluated on the testing data with batch size 16 and using CPU-inference. The evaluation focused both on the model performance and its computational efficiency.

The noted performance metrics were as follows:

- [email protected] and [email protected]:0.95 indicate how well the model balances precision and recall (at a fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 and across multiple IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95, respectively). Higher mAP values suggest more accurate localization and classification.

- Precision measures the model’s ability to make correct predictions. High precision indicates fewer false alarms.

- Recall showcases the model’s ability to detect all relevant objects. High recall can be essential in ensuring no obstacles are missed.

- Confusion matrix visualize which classes are frequently confused and highlight potential weaknesses in the model.

- Inference time is the average time taken per image to perform inference; it reflects real-time performance.

Two key metrics were used to evaluate computational requirements. First, model size was assessed by measuring the size of the exported .engine file for each model. Second, memory usage was evaluated using the Python library psutil (Rodola, 2025).Specifically, memory usage was recorded immediately before and after running inference on the full testing dataset with a batch size of 16. The difference between these values represented the memory used during inference.

Results

Performance

Table 1 summarizes the performance of all model variants and Figures 2 and 3 visualize it.

Table 1. Detection performance metrics on testing dataset

Figure 2. Detection performance across model variants

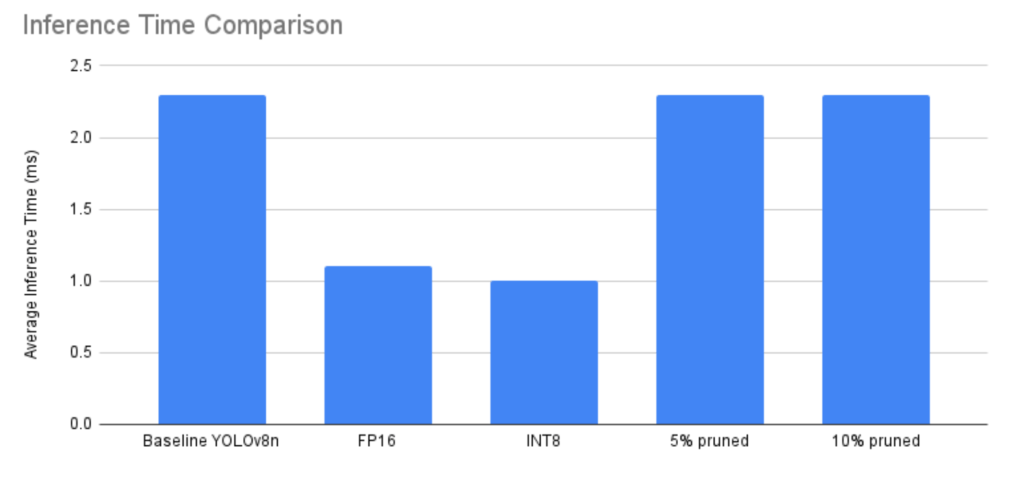

Figure 3. Inference Time across model variants

The baseline YOLOv8n model achieved a [email protected] of 0.799, [email protected]:0.95 of 0.600, precision of 0.690, recall of 0.817, and an average inference time of 2.3 milliseconds. The FP16 variant demonstrated nearly identically while reducing inference time to 1.1 milliseconds. The INT8 quantized model achieved the highest precision (0.741) and maintained competitive mAP scores ([email protected] = 0.801; [email protected]:0.95 = 0.587). It also reached the lowest inference time recorded at 1.0 milliseconds. The 5% pruned model, compared with the baseline, had a marginal decrease in performance and unchanged latency. Contrastingly, the 10% pruned model experienced a notable decline in performance due to the substantial reductions in precision (0.475) and recall (0.712).

3.2 Class-Specific Performance

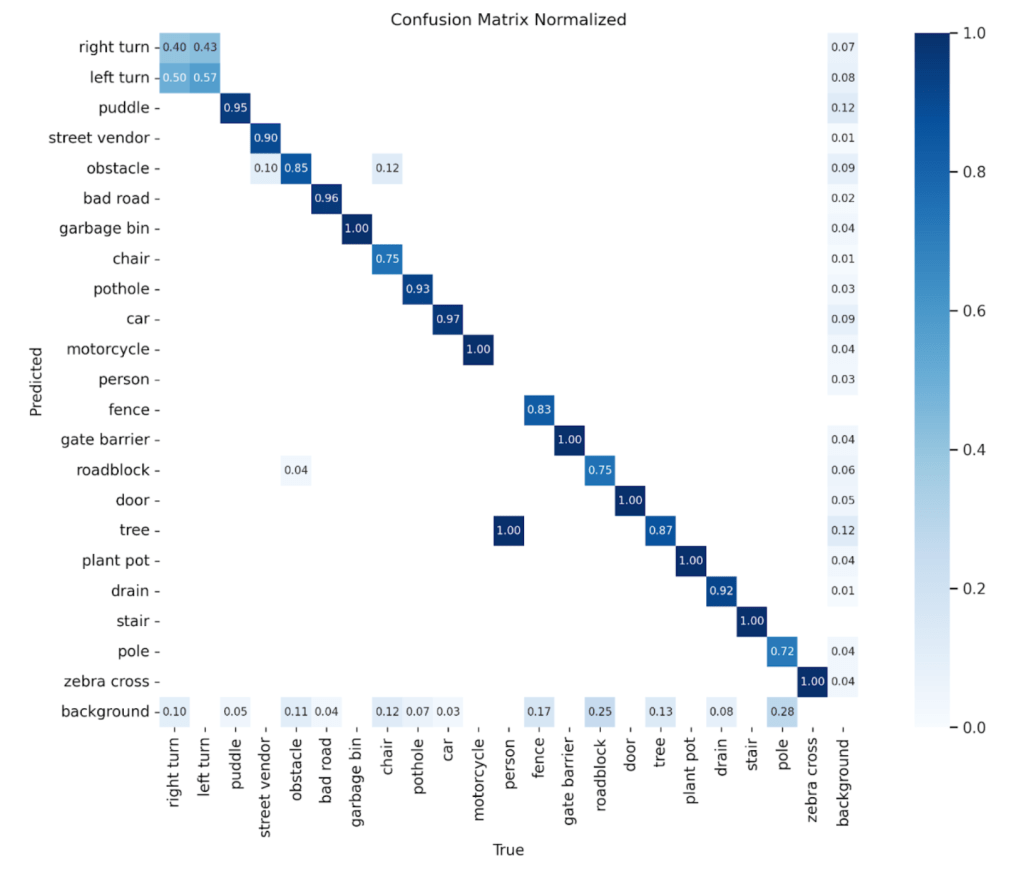

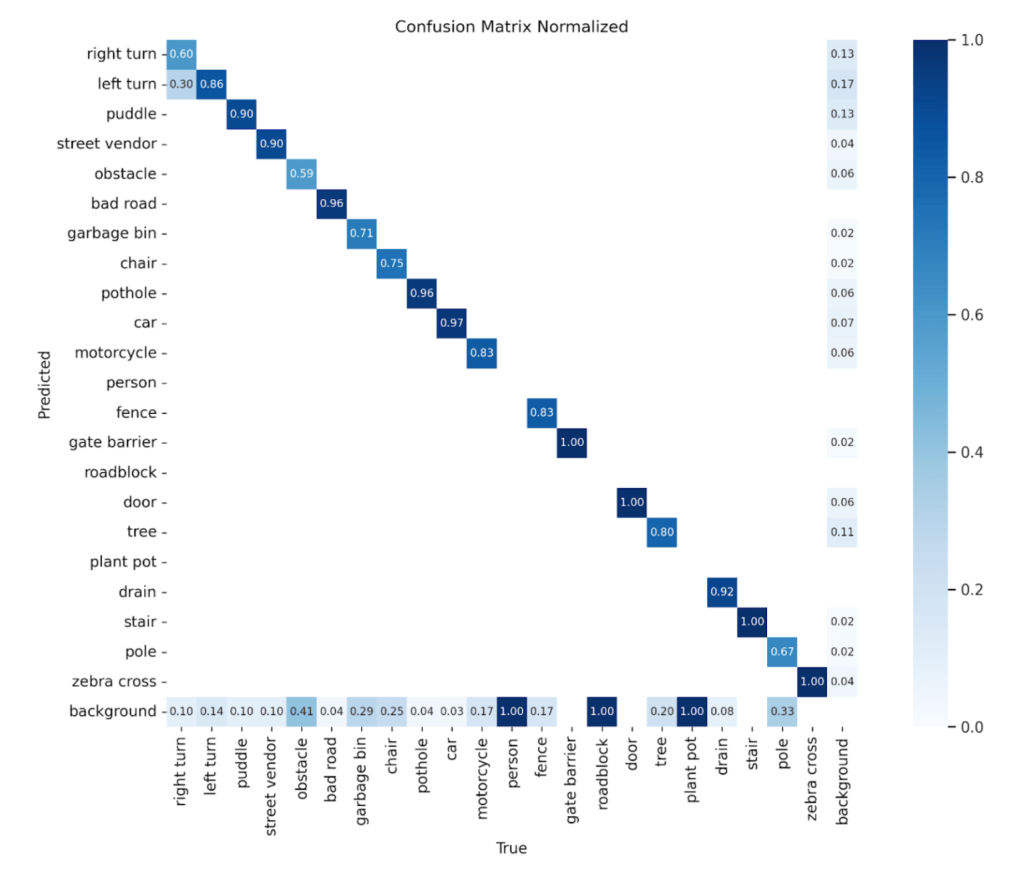

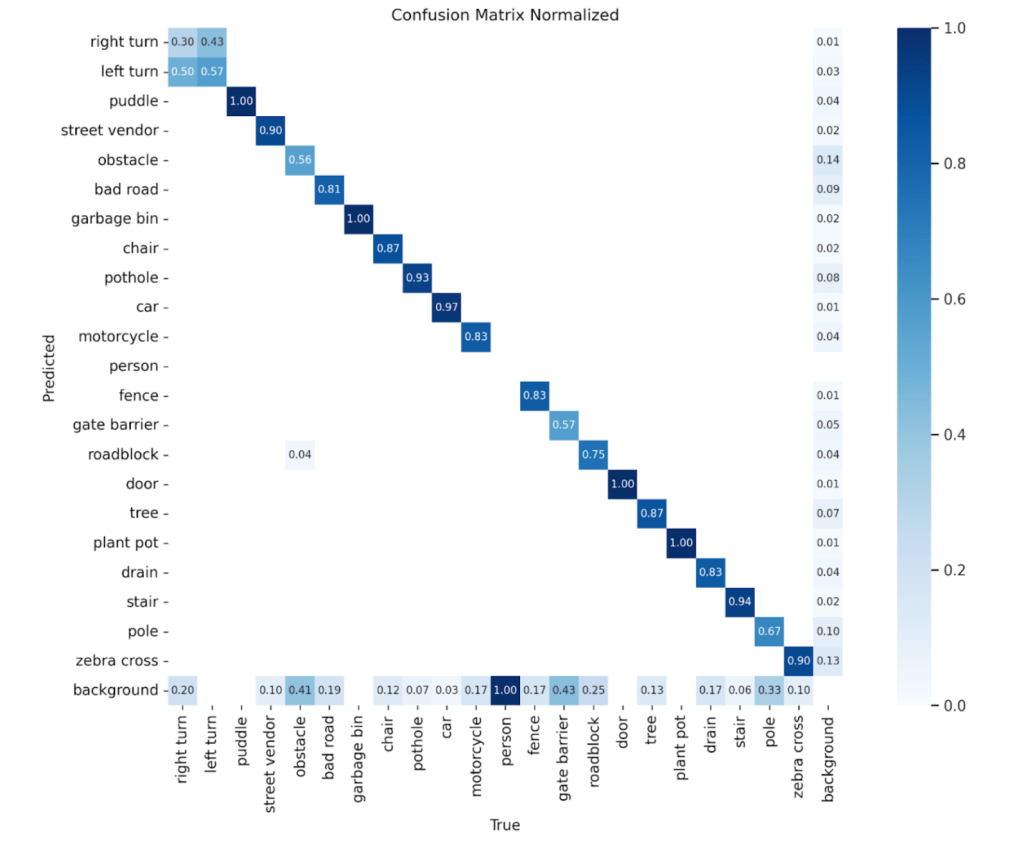

To illustrate class-wise detection performance, normalized confusion matrices are shown for three selected model variants: the baseline YOLOv8n, the INT8 quantized model, and the 10% pruned model. These variants were chosen to represent the performance benchmark, the quantized model with the best trade-off between accuracy and inference speed, and the most underperforming model, respectively. See Figures 4 to 6.

Figure 4. Confusion matrix of baseline YOLOv8n model.

Figure 5. Confusion matrix of INT8 quantized model.

Figure 6. Confusion matrix of 10% pruned model.

All three models demonstrated difficulty in accurately detecting the person class. The relative performance across classes is consistent across the models. The INT8 quantized model showed slightly lower performance compared to the baseline, while the 10% pruned model underperformed relative to both. Notably, the INT8 model exhibited a pronounced drop in accuracy for the roadblock class.

Computational Requirements

In terms of computational efficiency (Table 2), the INT8 quantized model achieved the smallest model size (7.23 MiB) and lowest memory usage (995.45 MiB), followed by the FP16 model (9.19 MiB, 1000.69 MiB). Meanwhile, the pruned models showed minimal reduction in model size and memory usage compared to the baseline.

Table 2. Model size and memory usage of models.

Discussion

Before interpreting the results, it is important to note that some obstacle classes—particularly person (1 instance) and plant pot (2 instances)—were severely underrepresented in the testing dataset. As such, any quantitative results related to these two classes should be interpreted cautiously, as they are not statistically significant. This limitation affected all model variants equally and likely contributed to observation that the models all struggled in accurately detecting the person class.

Quantization

Quantization proved to be an effective strategy for optimizing the YOLOv8n model on the specific object detection tasks—whether quantized to int8 or float16 format, the strategy significantly improved computational efficiency and inference time with minimal performance degradation. The INT8 model, in particular, achieved the fastest inference time (1.0 ms), the smallest model size (7.23 MiB), and the lowest memory usage (995.45 MiB), all while sustaining detection performance comparable to the baseline. These improvements support the central goal of this study: enabling reliable, real-time obstacle detection on low-power, resource-constrained edge devices. In the context of assistive technology, the reduced inference time observed in the INT8 model translates to faster alerts and smoother navigation experiences; meanwhile, smaller model size and lower memory consumption allow for deployment on compact devices (e.g., Raspberry Pi or wearables), and even the inclusion of additional assistive functions (e.g., text-to-speech or GPS) without exceeding hardware limits.

For both the INT8 and FLOAT16 model variants, the fact that efficiency gains were achieved with only minor drops in mAP suggests that quantization did not drastically compromise the model’s ability to localize and classify obstacles. This may be attributed to the robustness of the YOLOv8n architecture to quantization. Additionally, past studies have suggested the potential that quantization results in a regularization effect: by reducing numeric precision, the model may be less prone to overfitting subtle noise in the training data and perform better on unseen data (Tallec et al., 2023). Nonetheless, class-specific behavior reveals some nuances.

The INT8 model, while generally strong, showed reduced performance in detecting certain classes such as roadblock; considering that roadblocks tend to be more visually subtle and vary more in shape compared to other obstacles, this suggests that quantization may disproportionately impact classes with less distinctive visual features or greater intra-class variability. Additional calibration may be needed if future systems in object detection wish to prioritize detecting rare but critical obstacles.

Overall, the quantized YOLOv8n models—particularly INT8—offer a compelling solution to the problem of delivering fast, accurate, and lightweight obstacle detection in real-world assistive scenarios.

Pruning

Pruning, in contrast, had more nuanced and sometimes adverse effects. The 5% pruned model retained comparable accuracy to the baseline and showed no gain in inference time or resource usage. This may be a result of the interaction between pruning and YOLO’s deployment pipeline: removing filters doesn’t always translate to runtime efficiency unless the model’s backend is optimized to leverage the newly adopted sparser architecture. Also, modest pruning may not be enough to reduce model complexity unless accompanied by specific architectural simplifications.

With greater pruning, the 10% pruned model suffered a significant drop in detection performance across all metrics—an indication that overly aggressive pruning compromises performance. For critical applications like obstacle detection for visually impaired users, such degradation introduces unacceptable risk. Moreover, even with 10% of the filters removed, the model size and inference time remained nearly identical to the baseline, once again demonstrating that pruning without subsequent architectural optimization or backend acceleration does not meaningfully compact a model.

Conclusion & Future Directions

In summary, quantization offers a reliable pathway to improve model efficiency for edge deployment, particularly in the context of real-time obstacle detection. Particularly, INT8 quantization delivers strong performance, significant speedup, and compact size. Pruning, by contrast, needs more careful tuning. Light pruning may preserve accuracy, but it yields minimal efficiency gains—while excessive pruning can severely compromise model performance.

A key method to bypass the limitations of this research is the development or expansion of datasets with more balanced class representation. This would allow for statistically sound evaluation of model performance across all obstacle types. Additionally, incorporating data augmentation techniques—such as geometric transformations and lighting variations—could enhance the class diversity of a lacking dataset and improve model generalization. There are also multiple directions for future work to push the boundary of object detection model efficiency without compromising reliability. For instance, for quantization, employing quantization-aware training (QAT) or trying dynamic and mixed-precision quantization. For pruning, attempting the removal or manipulation of layers (e.g., combining convolution layers) instead of only filters, or pruning based on criteria more sophisticated than the L1 norm.

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank my mentor, Vincent Wong, for his invaluable support, insightful suggestions, and generous provision of GPU resources throughout the course of this research. His guidance played a crucial role in shaping both the technical direction and execution of the project.

References

Alahdal, N. M., Abukhodair, F., Meftah, L. H., & Cherif, A. (2024). Real-time Object Detection in Autonomous Vehicles with YOLO. Procedia Computer Science, 246, 2792–2801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.09.392

Anand, A., Suresh, D., AJ, M., S, P., & Zaheer, S. (2024). Implementation of Online Path Planning and Obstacle Avoidance Using Yolo for Autonomous Mobile Robots. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202406.1382.v1

Boesch, G. (2024, October 4). Object Detection in 2021: The Definitive Guide. Viso.ai. https://viso.ai/deep-learning/object-detection/

Dakopoulos, D., & Bourbakis, N. G. (2010). Wearable Obstacle Avoidance Electronic Travel Aids for Blind: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part c (Applications and Reviews), 40(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsmcc.2009.2021255

Feng, J., & Jin, T. (2024). CEH-YOLO: A composite enhanced YOLO-based model for underwater object detection. Ecological Informatics, 82, 102758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102758

Han, S., Mao, H., & Dally, W. J. (2016). Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1510.00149

Howard, A. G., Zhu, M., Chen, B., Kalenichenko, D., Wang, W., Weyand, T., Andreetto, M., & Adam, H. (2017). MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861

Lin, I-Fen., & Wu, H.-S. (2014). Activity Limitations, Use of Assistive Devices or Personal Help, and Well-Being: Variation by Education. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 1), S16–S25. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu115

Merugu, S., Ghinea, G., Subhani Shaik, A., Ahmed, M., & P, R. B. (2022). A Review of Some Assistive Tools and their Limitations for Visually Impaired. HELIX, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.29042/2022-12-1-1-9

Molchanov, P., Tyree, S., Karras, T., Aila, T., & Kautz, J. (2017). Pruning Convolutional Neural Networks for Resource Efficient Inference. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1611.06440

Mufti Restu Mahesa. (2024). Obstacles in Public Spaces for Dist-YOLO. Kaggle.com. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/muftirestumahesa/obstacles-in-public-spaces-for-dist-yolo

PyTorch. (2023). torch.nn.utils.prune.ln_structured — PyTorch 2.6 documentation. Pytorch.org. https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.nn.utils.prune.ln_structured.html

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. (2015). You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.02640

Rodola, G. (2025, February 13). psutil: Cross-platform lib for process and system monitoring in Python. PyPI. https://pypi.org/project/psutil/

Tallec, G., Yvinec, E., Dapogny, A., & Bailly, K. (2023). Fighting over-fitting with quantization for learning deep neural networks on noisy labels. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2303.11803

Ultralytics. (n.d.-a). Model Export with Ultralytics YOLO. Docs.ultralytics.com. https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/export/

Ultralytics. (n.d.-b). Model Training with Ultralytics YOLO. Docs.ultralytics.com. https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/train/

Ultralytics. (n.d.-c). YOLOv8. Docs.ultralytics.com. https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8

Wang, W., Jing, B., Yu, X., Sun, Y., Yang, L., & Wang, C. (2024). YOLO-OD: Obstacle Detection for Visually Impaired Navigation Assistance. Sensors, 24(23), 7621–7621. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24237621

Zhou, A., Yao, A., Guo, Y., Xu, L., & Chen, Y. (2017). Incremental Network Quantization: Towards Lossless CNNs with Low-Precision Weights. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1702.03044