Alexandra Ye – Applied Science, Year 2

Abstract

This study investigates the impact of dropper tip geometry on eye drop volume and usability, in order to reduce medication waste and improve dosing accuracy. Four 3D-printed prototypes with varying internal and external structures were designed and tested against a commercial control using standardized saline trials. Drop size was measured by mass of 10 drops per trial to overcome limitations in precision. Results showed that pointed tips produced significantly smaller drops than flat ones while internal geometry had minimal effect. Although three prototypes showed statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements, differences in material composition between the prototypes (PLA) and the control (PE) were identified as a potentially significant confounding factor. Findings support further exploration of tip design and material compatibility to enhance ophthalmic drug delivery.

Introduction

Eyes are one of most important organs; they allow living beings to see and interact with the world around them. As humans, it is important for us to understand how to take care of our eyes to prolong their well-being. With that said, eye droppers are a simple, yet essential tool used for all sorts of eye care scenarios. One way eye droppers are used is to administer artificial tears, or lubricating eye drops. These are commonly used to relieve dry eye discomfort caused by long hours in front of a screen, fatigue, or dry environments (Boyd, 2022). For more serious conditions, such as bacterial eye infections, antibiotics can be prescribed also in the form of eye drops to directly kill the malicious bacteria (Porter, 2024). Eye drops are particularly popular because they are non-invasive and easy to use. In fact, up to 90% of marketed ophthalmic formulations are eye drops (Patel et al., 2013). The convenience and effectiveness of eye droppers makes them a critical tool in both treating and preventing eye conditions, but they are not without their limitations.

Eye drops, despite their widespread use and convenience, are associated with several medical challenges. One significant issue is the potential for systemic side effects, even when the medication is applied correctly. According to Farkouh et al. (2016), the active ingredients in ophthalmic drugs are often highly concentrated and a portion of the administered drug may be absorbed into the rest of the body through unintended routes, such as the lacrimal drainage system. This can lead to excess bioavailability, which is particularly concerning in children, who are more vulnerable to adverse effects due to their smaller body size and underdeveloped metabolic systems. The lack of weight-adjusted dosing in pediatric ophthalmology further compounds this issue, and Farkouh et al. emphasize that current investigations on pediatric dosing are limited.

Another problem lies in the variability of drop volumes delivered by multi-dose eye drop bottles. German et al. (1999) found that the drop size can range significantly (from 33.8 µl to 63.4 µl) depending on factors such as the handling angle of the bottle. The study highlights that the amount of drug administered is proportional to drop sizes. The combination of larger drops of higher concentration gives excess medication, worsening the previously mentioned problem of bioavailability. The researchers also noted that there are currently no regulations in the UK or USA governing drop volume, even though drug volume significantly affects drug efficacy. This variability could impact therapeutic efficacy and lead to inconsistent treatment outcomes.

Van Santvliet and Ludwig (2004) delve deeper into the biopharmaceutical and technical aspects of eye drops, pointing out that the typical drop size of 25-70 µl exceeds the eye’s capacity of 7-10 µl, resulting in significant waste and reduced efficiency. From both a therapeutic and economic perspective, 5 to 15 µl is the perfect volume to maximize efficiency and minimize waste. Their review also discusses factors that determine drop size, such as surface tension, viscosity, and the design of the dropper tip. The authors concluded that an optimal dropper tip should have a narrow outer orifice and a well-defined surface area to ensure consistent drop formation and controlled release. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing dropper design to ensure both precision and efficiency.

Reviewing previous literature indicates that there is a clear issue with current eye dropper designs, as they often fail to deliver the optimal dosage of medication. Given the widespread reliance on eye drops for various medical conditions, this inefficiency is both economically and therapeutically unsustainable (Patel et al., 2013). A study that experimentally investigates dropper tip designs could provide a solution by identifying features that consistently deliver the correct dosage with minimal effort. Specifically, this study will focus on optimizing the shape and structure of the dropper tip to regulate drop volume. Through controlled experimental testing and iterative prototyping, this research aims to develop a dropper tip that enhances dosing precision and minimizes medication waste. Filling this gap will not only benefit patients but also improve the effectiveness and usability of ophthalmic treatments overall.

Materials and Methods

Designing the Dropper Tips

Before designing, proper measurements of the testing bottle were taken for reference. The bottle used for this experiment was a conventional multi-dose dropper bottle with a squeezable plastic body belonging to an expired 0.02% atropine solution. First, the tip of the testing bottle was removed with a pair of pliers and the inside of the dropper bottle was washed with soap and water and dried. Then, a digital caliper was used to measure the inner diameter of the neck of the bottle, as well as the height. These measurements were noted in a document for reference throughout the design process.

The design process began with sketching cross-sectional diagrams of dropper tips on paper, modifying variables such as internal structure and nozzle shape to explore different configurations (Figure 1). These sketches were scanned and uploaded into Autodesk Fusion, where they served as a reference for digital modeling. Using Autodesk Fusion’s Sketch Tool, an outline of each dropper tip was traced based on the scanned design. The Revolve Tool was then be used to convert the 2D sketch into a symmetrical 3D model (Figure 2). Once finalized, the dropper tip designs were exported as .STL files, which was used for slicing and 3D printing.

Figure 1: Hand drawn sketches of initial dropper tip designs

Figure 2: Sample CAD model of finalized dropper tip created in Autodesk Fusion

A total of four dropper tip designs were created for testing while Dropper A, the dropper that came with the bottle, served as the control. Dropper B featured a smooth, sloped interior that ended in a concave tip, intended to observe how a streamlined internal channel might affect drop formation. Dropper C had a wider internal channel and a flat, circular tip, designed to test the impact of both larger volume flow and increased surface area. Dropper D introduced a narrow, completely vertical interior, aiming to regulate flow through internal constriction. Lastly, Dropper E combined a pointed tip with sharp internal ridges to evaluate whether abrupt internal angles influenced drop behavior.

3D Printing Process

The .STL file from Autodesk Fusion was imported into Bambu Studio, the slicing application for the Bambu Lab X1 Carbon 3D printer. This program converted the 3D model into a layer-by-layer sliced format for printing. The slicing settings were configured to a layer height of 0.20 mm and an initial layer height of 0.20 mm under the “Quality” tab. Seam position was set to Aligned, and advanced settings enabled only one wall on top surfaces. Furthermore, the system preset was set to 0.20mm Standard @BBL X1C.

To ensure a flush and thus stable connection between the tip and the bottle, all droppers were printed upside down. This orientation helped prevent warping at the base of the dropper. However, printing in this orientation introduced overhangs near the nozzle tip. Bambu Studio addressed this by automatically generating scaffolding supports, which were manually removed after printing with pliers. The final print file was then saved as a .GCODE.3MF file and transferred to a microSD card for insertion into the side of the 3D printer’s screen. Printing was carried out using a basic PLA filament with a 0.4 mm nozzle on a textured PEI plate.

Iterative Refinement of Prototypes

Before testing, the printed dropper tips underwent an iterative refinement process to assess their fit and functionality. Each prototype was visually inspected and qualitatively evaluated to check whether it attached securely to the bottle and had a properly formed orifice for liquid passage. To limit PLA wastage, unfit prototypes were first modified by hand in several manners. Plugged tips were lightly sanded to reveal the underlying orifice while droppers with narrow bases were covered in 1-2 layers of masking tape to ensure tighter fit onto the bottle. If these manual fixes were unsuccessful, the models were revised in Autodesk Fusion and reprinted. Each design underwent this cycle of printing, inspection, and digital modification as many times as necessary until a functional version was achieved. Only after one design was finalized did the process begin again for the next, continuing until four viable prototypes were ready for testing. Once these designs were finalized, the study proceeded to formal testing, where quantitative measurements were taken to evaluate drop volume and excess liquid retention.

Testing Procedure and Data Collection

The eye dropper prototypes were tested with 15.00g of 0.9% saline, as it is often used to simulate real-world ophthalmic fluids (Barabino et al., 2005). Each trial consisted of measuring the mass of 10 drops in a container with a precision balance. Each dropper prototype underwent 10 such trials.

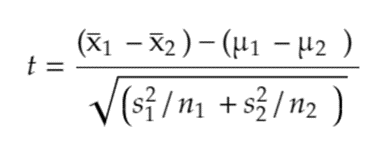

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the modified dropper tips, a Two-Sample t-test Assuming Unequal Variances was performed. This test compared the observed performance of each 3D-printed dropper tip to the control dropper tip (dropper A), providing an overview of how each prototype deviates from the standard commercially available design. The t value, calculated from (1) determined whether differences in drop sizes were due to random variation or were statistically significant.

A two-tailed test was used because there is no prior evidence to suggest whether the modified dropper tips would produce larger or smaller drops compared to the standard. Therefore, the analysis needed to account for the possibility of differences in either direction, making a two-tailed test the most appropriate and safe approach.

In this analysis, the average mass per individual drop was not calculated to avoid unnecessary manipulation of the data. Every trial for each dropper involved exactly 10 drops, and other conditions, such as using fully filled bottles and the same vial of saline solution, were kept constant. Therefore, direct comparison of the total mass across samples remained valid and statistically meaningful.

The alpha (α) level was set to 0.05, the standard threshold in scientific research. If the p-value falls below 0.05, it will confirm that the selected dropper tip design provided a measurable improvement. Excess liquid retention was not measured due to difficulties in instrumentation; however, it was qualitatively observed to be negligible across droppers 1, 3 and 4.

Results and Data Analysis

Table 1: Data collected from the control dropper (Dropper A)

Table 2: Data collected from Dropper B and Excel’s corresponding statistical test

Table 3: Data collected from Dropper C and Excel’s corresponding statistical test

Table 4: Data collected from Dropper D and Excel’s corresponding statistical test

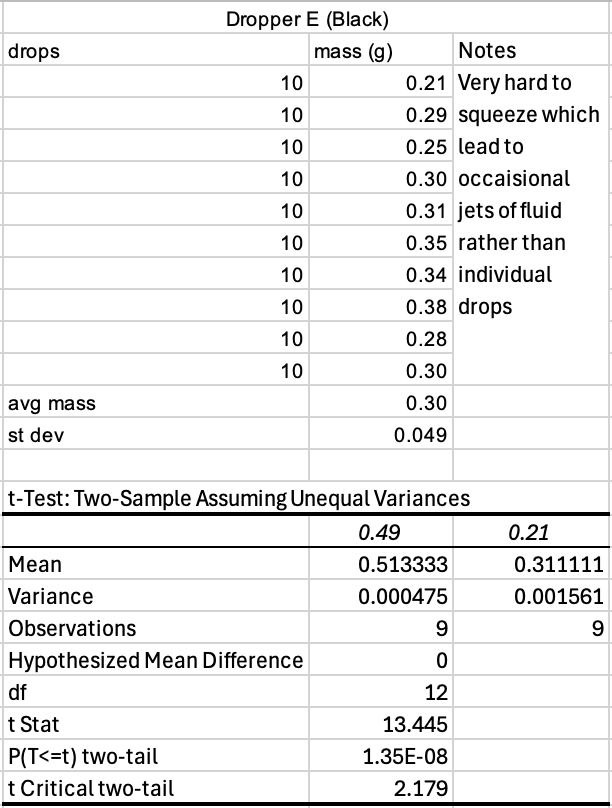

Table 5: Data collected from Dropper E and Excel’s corresponding statistical test

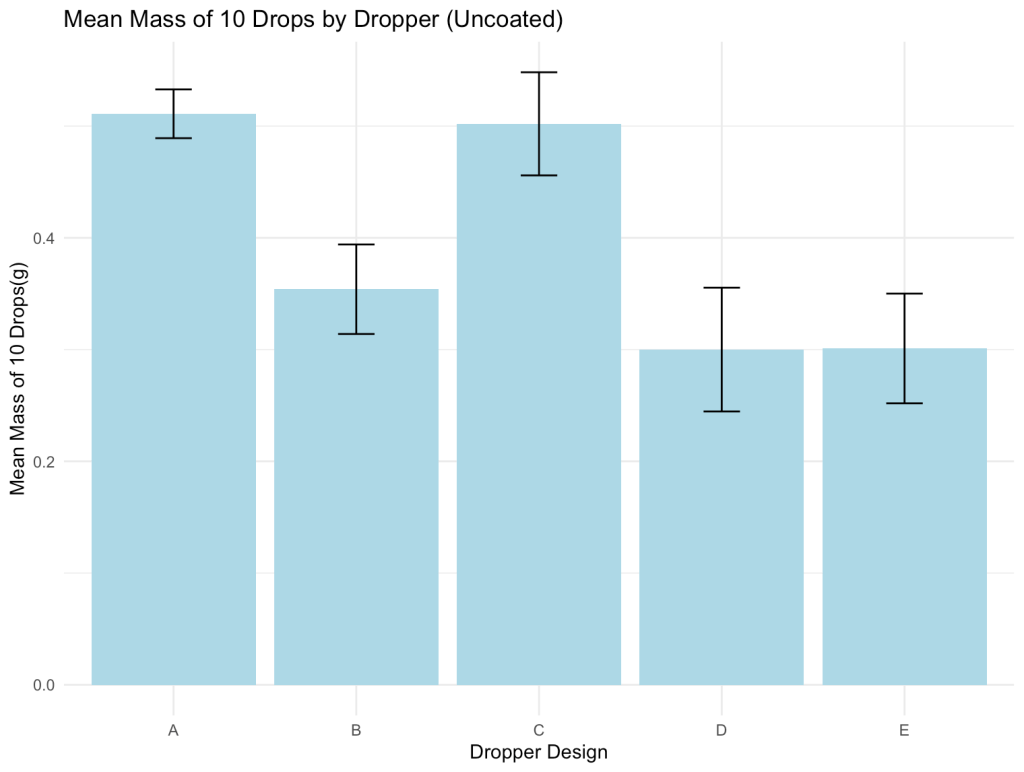

Figure 3: Comparison of average mass of 10 drops across control and prototype designs

Discussion

During the printing process, it was found that orienting the dropper tips upside down produced more reliable results. This method ensured that the connecting edge between the dropper tip and the plug portion of the base remained at a 90º angle. As a result of this consistent angle throughout the circumference, the dropper seemed to fit more snug in the mouth of the bottle. When printed right side up, the tips exhibited slight deformation at the nozzle due to drooping, which led to inconsistencies in the connection point. However, printing upside down introduced a new challenge: ensuring the internal hole remained open. In the case of Dropper D v2, excess filament pooled during printing and obstructed the internal channel entirely, despite manual attempts at sanding and using a needle to reopen the orifice.

As for the experimental results, each prototype yielded unique outcomes in both drop size and usability. Dropper B (Yellow) demonstrated the most promising balance overall, producing statistically smaller drop sizes while remaining easy to handle. Its performance suggests strong potential for reducing medication waste and limiting systemic absorption. Dropper E (Black), although producing the smallest drops among all tested designs, presented significant usability challenges. It required excessive squeezing force, showed frequent leakage, and occasionally formed a jet stream of saline rather than individual drops. Ultimately this dropper is impractical despite its precision. Dropper D (Red) also achieved a meaningful reduction in drop size; however, its output was difficult to control, often releasing multiple drops by accident. In contrast, Dropper C (Black) performed similarly to Dropper A (the control) across all metrics, suggesting that its design did not offer any significant improvements.

Droppers B, D and E each yielded statistically significant differences, while Dropper C did not. This discrepancy invites a closer look at each prototype’s design. Although the interior geometries of Droppers B, D, and E varied, they produced similar drop sizes, suggesting that internal structure may not be the most influential factor in determining drop size. Instead, a visual comparison between Dropper C and the other three designs revealed a possible explanation: Dropper C had a flat circular tip with a 4 mm diameter, whereas the others featured a sharp point or dome with a surface diameter of 1-2 mm. It was also observed that liquid tended to cling to the broad tip of Dropper C and accumulate before falling off, thus resulting in larger drops. This suggests that the surface area at the very tip of the dropper is likely the most critical factor in controlling drop size.

Despite the promising findings, the study is not without limitations. First, the results are only generalizable to squeeze bottles that use a plug-and-hole attachment mechanism. Additionally, most commercially available 3D printers are not certified for medical-grade applications and may not be safe for direct contact with ophthalmic medications due to potential contamination or residue. Therefore, this study can only serve as a proof of concept for the feasibility of altering eye dropper tip parameters to decrease drop size.

One of the most significant confounding variables in this study is the difference in material composition between the control dropper and the 3D-printed prototypes. Most commercial eye droppers are manufactured through injection molding using polyethylene (PE), while all prototypes in this study were printed using polylactic acid (PLA). These two materials differ in surface properties and interactions with saline solution, which may have influenced how droplets formed, potentially skewing the results.

Future research could examine material properties more directly. For instance, coating dropper tips with a hydrophobic substance like Vaseline was briefly explored. The goal was to reduce the contact angle and encourage smaller droplet formation. While preliminary results showed promise, this method was ultimately excluded to maintain the study’s focus on mechanical design factors. Moreover, Vaseline is not a practical solution for real-world use, as it could interfere with medication delivery or patient safety.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that modifying dropper tip geometry can significantly impact drop size and usability. While three of the four prototypes outperformed the control, material differences remain a key confounding variable. Future research should explore alternative materials and refine tip design to further enhance dosing precision.

Works Cited

Barabino, S., Rolando, M., Camicione, P., Chen, W., & Calabria, G. (2005). Effects of a 0.9% sodium chloride ophthalmic solution on the ocular surface of symptomatic contact lens wearers. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d’ophtalmologie, 40(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80116-4

Boyd, K. (2022, February 9). Lubricating Eye Drops for Dry Eyes. American Academy of Ophthalmology https://www.aao.org/eye-health/treatments/lubricating-eye-drops

Farkouh, A., Frigo, P., & Czejka, M. (2016). Systemic side effects of eye drops: a pharmacokinetic perspective. Clinical Ophthalmology, 10, 2433–2441. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S118409

German, E., Hurst, M. & Wood, D (1999). Reliability of drop size from multi-dose eye drop bottles: is it cause for concern?. Eye 13, 93–100 . https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1999.17

Patel, A., Cholkar, K., Agrahari, V., & Mitra, A. K. (2013). Ocular drug delivery systems: An overview. World Journal of Pharmacology, 2(2), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.5497/wjp.v2.i2.47

Porter, D. (2024, October 24). Antibiotic Eye Drops. American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Van Santvliet, L. & Ludwig, A. (2004). Determinants of eye drop size, Survey of Ophthalmology, Volume 49, Issue 2, Pages 197-213, ISSN 0039-6257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.009.