Tanya Liu – Life Science

Abstract

This project explores a cost-effective DIY approach to micropropagation, aiming to make plant tissue culture accessible to hobbyists and small-scale projects. Micropropagation is the culturing of plant tissues in controlled environments and typically requires expensive equipment and high level of care. By using affordable alternatives such as small pressure cookers and glass canning jars, this project seeks successful plant growth and multiplication under budget-friendly conditions. Murashige and Skoog medium is used as the primary growth medium, supplemented with sugar and the antibiotic Tetracycline HCl to enhance growth and prevent contamination. Two trials were conducted to evaluate the effects of varying antibiotic concentrations on the success of plant growth and bacterial and fungal contamination. Results showed a reduction in contamination with higher Tetracycline HCI concentrations, though no significant plant growth was observed.

Introduction

Micropropagation is the culturing of plant tissues and organs in closed vessels filled with specialized culture media under controlled environmental conditions (Loberant & Altman, 2010) It allows for rapid generation of a large number of clonal plants and has thus become a standard tool used in conservation, genetic engineering, and biotechnology. (Read, 2007) Successful micropropagation saves excessive amounts of a grower’s time, labor, and space spent on unproductive seeds, cuttings, and grafts. Tissue cultured plantlets, grown under sterile environments of the laboratory, are much less subject to attacks from pests, diseases, and other environmental risks. (Kyte et al, 2013)

In a traditional lab setting, specialized equipment and infrastructure are used to facilitate the culturing process. Cleanrooms, growth chambers, and sterile workstations are carefully observed to ensure sterile and controlled conditions (humidity, light, etc..) are maintained. (Sahu & Sahu, 2013) Equipment such as laminar flow hoods and autoclaves are also very expensive and difficult to acquire, bringing the total cost of a traditional set up around $20,000 to $50,000. Today, many hobbyists have adopted plant tissue culture methods for at-home micropropagation. Substitutes such as small pressure cookers for autoclaves and glass canning jars for culture vessels can be used to make the process more affordable and accessible. (Purohit et al, 2011) A pressure cooker typically costs around $100 and tissue culture starter kits can be purchased for $80, keeping the total cost under a friendly $200. (Singh, 2023)

This project addresses the challenge of accessibility by proposing a cost-effective DIY approach to micropropagation, making plant culturing possible for individuals and small-scale projects. Through the project, the successful growth and multiplication of plants using budget-friendly alternatives to micropropagation will be analyzed. A pre-mix with all the essential ingredients for the Murashige and Skoog medium (MS medium) will be used, along with sugar as an additional energy source. The effects of these growth regulators to the culture media will be observed. To reduce the risk of bacteria growth, Tetracycline HCL will be used as an antibiotic. Tetracycline is one of the three classes of antibiotics regularly used in plant production as they are well known for their broad spectrum of activity. (Grossman, 2016) It is relatively inexpensive to purchase and only requires standard refrigeration for storage.

Different from many already pre-existing at-home propagation protocols that use larger cuttings with water as its rooting medium, this project emphasizes small-cutting culturing. The explants go through several passages in MS medium and the development of explants through the various passages will be tracked. It is to note that this project was conducted in a classroom setting, where incubators, petri dishes, and other common lab equipment were readily accessible.

Materials and Methods

Material Sterilization

Pruning shears/scissors and tweezers were sterilized by soaking them in 20% bleach and 80% distilled water for 10 minutes.

Explant Extraction

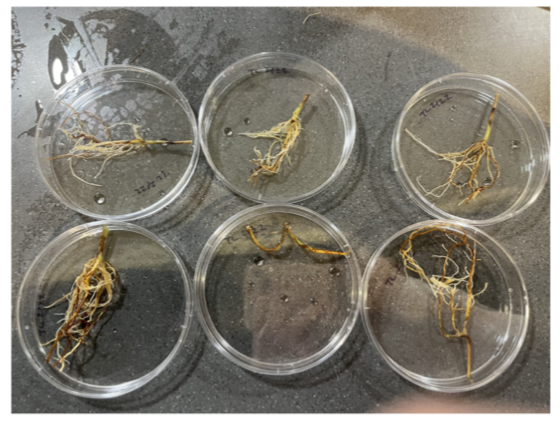

Orchids were used as the parent plant for this culture. Using sterilized pruning shears/scissors, three 5cm cuttings were cut from both the root and the stem of the parent plant. The explants were transferred to a solution consisting of 20% bleach and 80% distilled water using sterilized tweezers, where they were allowed to soak for 10 minutes (Figure 1). Then, the explants were rinsed thoroughly in 100% distilled water.

Figure 1: Plant sterilization solution – 80% distilled water + 20% bleach beaker & 100% distilled water

Media Preparation

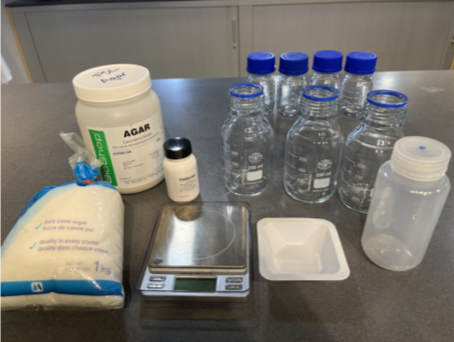

To prepare 1 liter of plant growth medium, 4.54 grams of Murashige and Skoog medium (Merlan) and 30 grams of sugar were added to 800 mL of distilled water (Figure 2). The solutes were ensured to be fully dissolved, then distilled water was added until the 950 mlmark. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.8-6.0. Once the pH was within the desired range, 15 g of sugar was added to the medium. Distilled water was slowly added to the medium slowly until the total volume reached 1 l. The prepared medium was divided into four 250 ml bottles.

Figure 2: Materials and equipment (left to right): sugar, agar, Murashige and Skoog medium, scale, bottles, weighing boat

A pressure cooker was used to sterilize the media. One inch of water was placed in the bottom of the cooker, with the pan with legs placed at the bottom. The bottles of media were placed inside the pressure cooker with lids unscrewed and were heated for one hour at 15PSI. After sterilization, 0.5 g of Tetracycline HCl (Bioshop) was mixed into each bottle, and the medium was allowed to cool before use. Tetracycline HCl served as an antibiotic, providing additional prevention against contamination.

Petri Dish Preparation and Storage

Six sterile Petri dishes were prepared and one explant was placed in each plate (Figure 3). The cooled media was poured onto each plate until the explant was fully submerged. To ensure the environment was as sterile as possible, the pouring process was conducted near a candle. Once the media solidified, the Petri dishes were incubated at 25°C and the growth of the plants was monitored.

Figure 3: Explants in Petri dishes before medium is poured in

Repetition of Trials

In total, two trials were conducted. During the second trial, a Tetracycline HCI (Bioshop) concentration of 1 g was used, doubling its concentration from the first trial.

Results

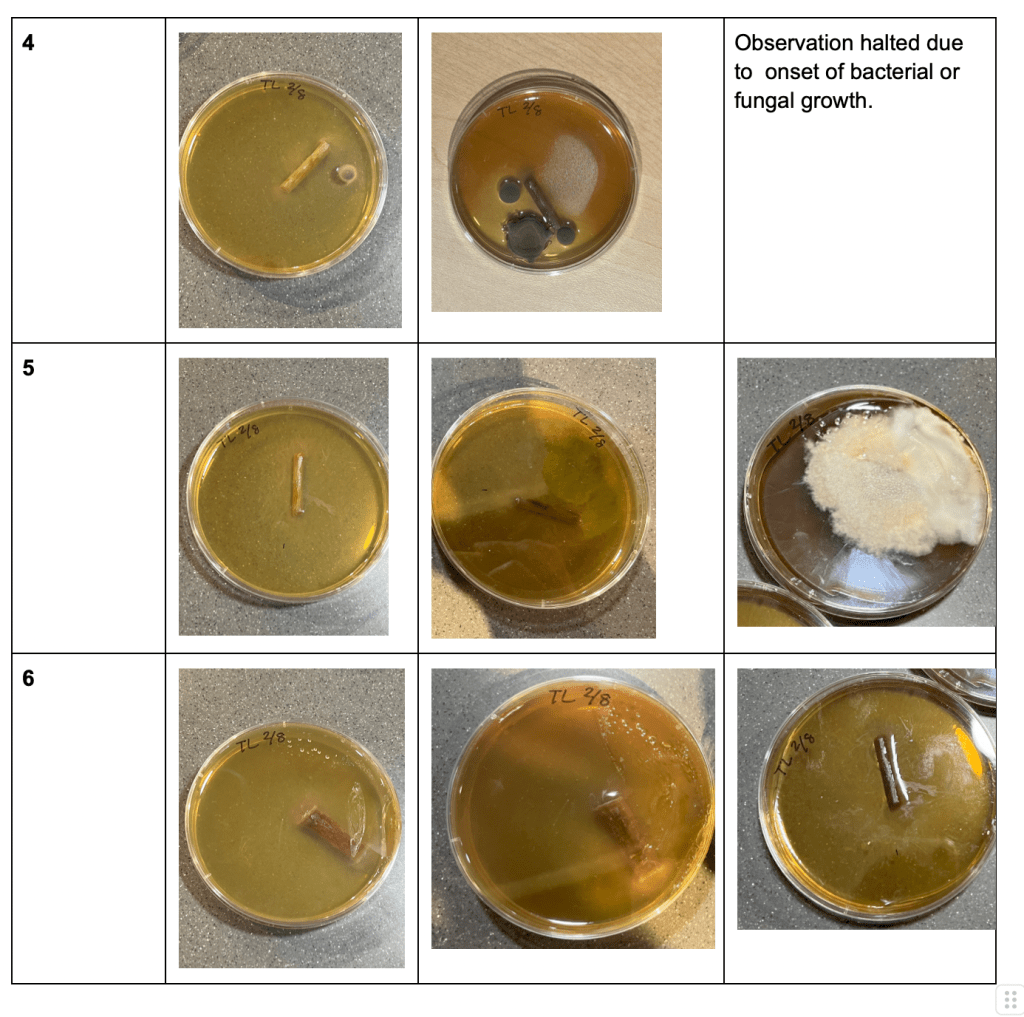

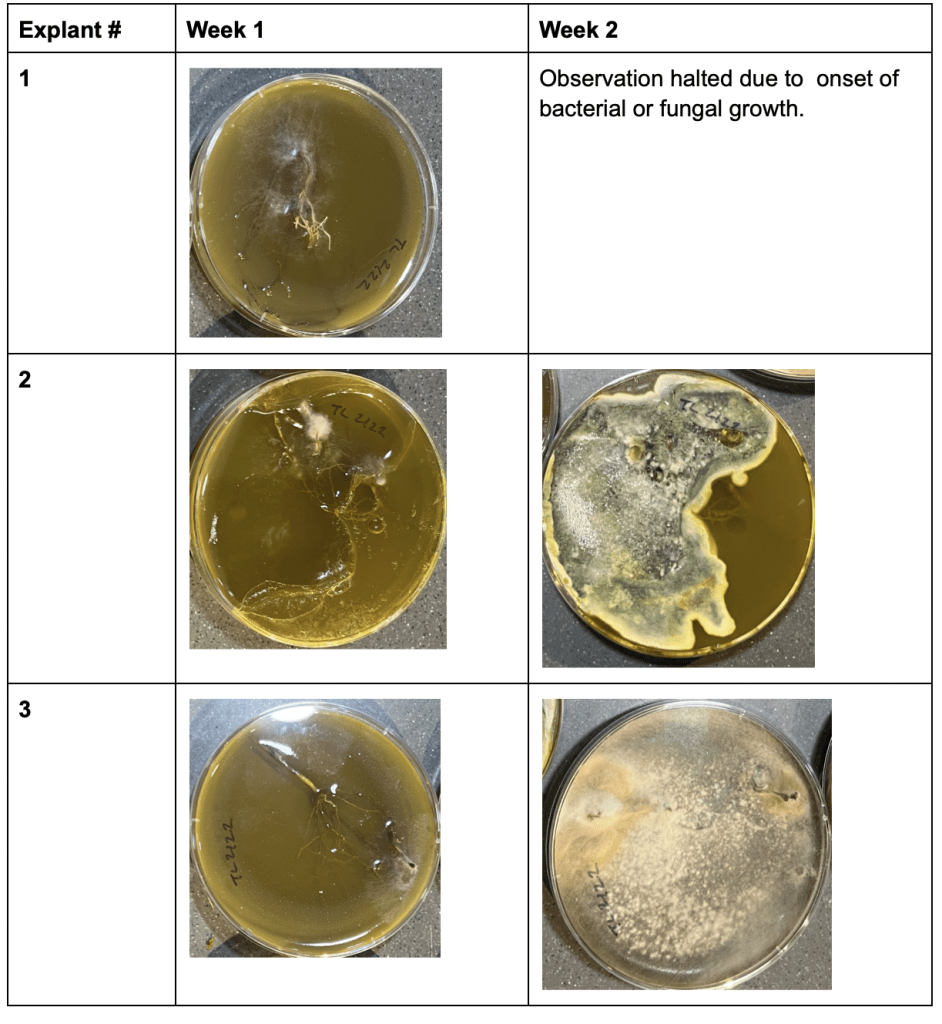

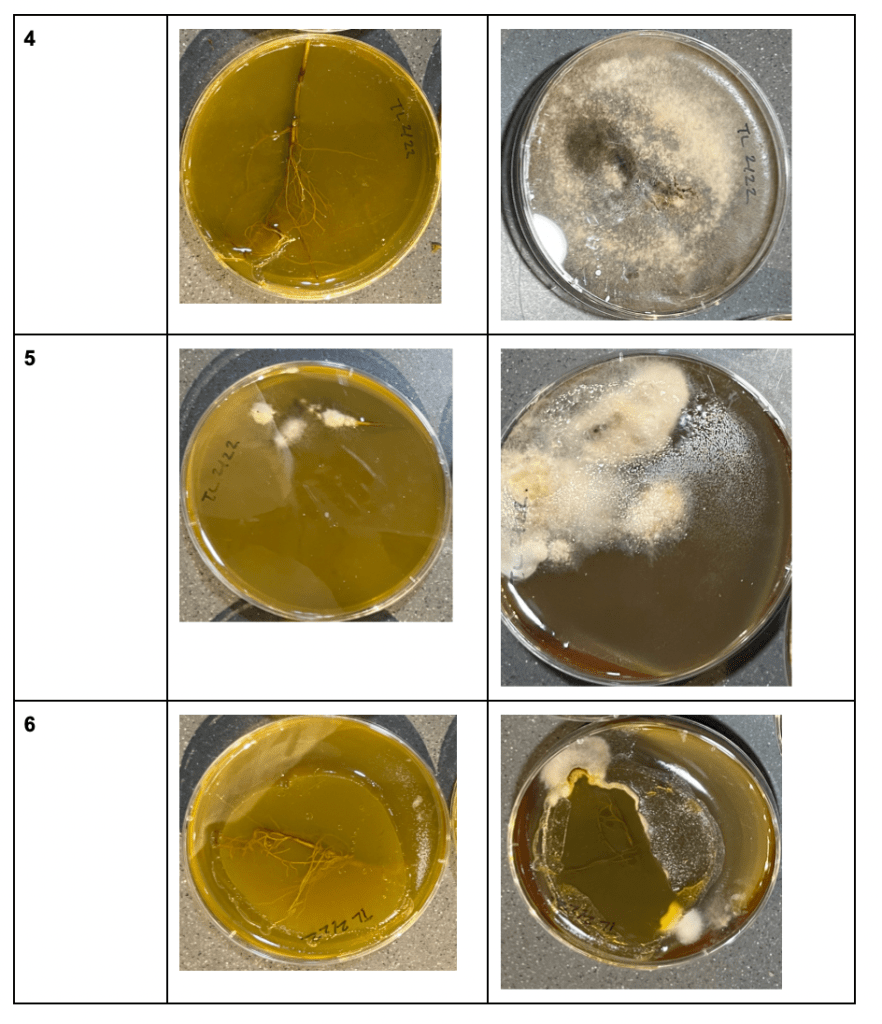

Each Petri Dish from both trials was monitored until the onset of bacterial or fungal growth. The bacterial or fungal growth on petri dishes exhibited variations, as depicted in the Tables 1 and 2.

During Trial 1 (Table 1), bacterial or fungal growth was observed in four Petri Dishes within the initial week, with an additional Petri Dish displaying such growth during the second week. Petri Dish #6 showed successful growth of the explant without any bacterial or fungal contamination. No significant stem growth was observed.

Table 1: Trial 1 Observations

During Trial 2, bacterial or fungal growth was observed in two Petri Dishes within the initial week, with three additional Petri Dishes displaying such growth during the second week. Petri Dish #1 showed successful growth of the explant without any bacterial or fungal contamination. No significant stem or root growth was observed.

Table 2: Trial 2 Observations

Discussion

This project aimed to monitor shoot and root development in small-sized explants through micropropagation in a classroom setting. However, the intended shoot and root development was not observed in the successful plant cell cultures. This may be due to the limited time frame, as each trial was conducted for less than a month. To monitor the full growth of the plants, 2-3 months of observation with media transfers should take place.

Because simplifications were made to the traditional micropropagation techniques used in labs, particularly in protocols aimed at preserving a sterile environment, it is possible that the plates were subjected to environmental pathogens during the media pouring process. Cross-contamination could have occurred if (1) explants were not sterilized, (2) tools used to transfer explants were non sterilized, and (3) culture medium was exposed to the external environment.

Although Tetracycline HCl was used as an antibiotic, the dosage used could not be accurately measured due to the limitation of scale increments. A higher dosage than called for by the protocol was utilized to reduce the risk of insufficient dosage leading to bacterial growth.

It was observed that the effectiveness of Tetracycline HCl in inhibiting microbial growth correlated with its dosage. The doubled quantity of Tetracycline HCl in the second trial resulted in reduced microbial growth within the first week. In the first trial, 50% of the Petri dishes exhibited microbial growth, whereas only 16% did in the second trial during the same period.

For future experimentation, more trials should be conducted for an extended duration so the full growth cycle of the explants can be observed. The environment should be monitored more carefully to maintain a constant sterile condition. For example, a DIY fume hood can be made by using plywood sheets with a simple fan and filter (Forest, 2022) If budget allows, Plant Preservative Mixture (Plant Cell Technology), a heat stable preservative used to prevent microbial contamination in plant tissue culture, and additional types of antibiotics could be used to cover a broader scope of bacterial growth prevention.

In conclusion, this project highlights the importance of specialized equipment and infrastructure used to facilitate the culturing process. While cost-effective alternatives are available, they pose a higher risk of contamination, potentially leading to unsuccessful plant cultures. However, if successful, at-home plant culturing opens the door for individuals and small-scale projects to partake in the advancement of plant science and further enriches our understanding of plant propagation and its applications.

References

Abdalla, N., El-Ramady, H., Seliem, M. K., El-Mahrouk, M. E., Taha, N., Bayoumi, Y., Shalaby, T. A., & Dobránszki, J. (2022). An academic and technical overview on plant micropropagation challenges. Horticulturae, 8(8), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8080677

Abrahamian, P., & Kantharajah, A. (2011). Effect of vitamins on in vitro organogenesis of plant. American Journal of Plant Sciences, 02(05), 669–674. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2011.25080

Eibl, R., Meier, P., Stutz, I., Schildberger, D., Hühn, T., & Eibl, D. (2018). Plant Cell Culture Technology in the cosmetics and Food Industries: Current State and future trends. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102(20), 8661–8675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9279-8

Gamborg, O. L., Murashige, T., Thorpe, T. A., & Vasil, I. K. (1976). Plant Tissue Culture Media. In Vitro, 12(7), 473–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02796489

Grossman, T. H. (2016). Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025387

Kyte, L. (2013). Plants from test tubes: An introduction to micropropagation. Timber Press.

Loberant, B., & Altman, A. (2010). Micropropagation of plants. Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470054581.eib442

Purohit, S. D., & Habibi, N. (2014). Micropropagation of some medicinal plants of Aravallis in Rajasthan – cheaper and better options. Acta Horticulturae, (1030), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.2014.1030.13

Read, P. E. (2007). Micropropagation: Past, present and future. Acta Horticulturae, (748), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.2007.748.1

Sahu, J, & Sahu, R. J. (2013). A review on low cost methods for in vitro micropropagation of plants through tissue culture technique. Pharmaceutical and Biosciences Journal, 38–41. https://doi.org/10.20510/ukjpb/1/i1/91115

Thorpe, T. A. (2007). History of plant tissue culture. Plant Cell Culture Protocols, 009–032. https://doi.org/10.1385/1-59259-959-1:009